I’m wearing an orange stole today and a couple of you asked me on the way into church, “What season is orange?” Well, it’s not a seasonal stole … although I suppose we could say it commemorates the season of unregulated and out of control gun violence. A few years ago, a young woman named Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed in Chicago; her friends began wearing orange, like hunters wear for safety, in her honor on her birthday in June. A couple of years ago, Bishops Against Gun Violence, an Episcopal group, became a co-sponsor of Wear Orange Day and some of us clergy here in Ohio decided to make and wear orange stoles on the following Sunday. Our decision got press notice and spread to clergy of several denominations all over the country.

I’m wearing an orange stole today and a couple of you asked me on the way into church, “What season is orange?” Well, it’s not a seasonal stole … although I suppose we could say it commemorates the season of unregulated and out of control gun violence. A few years ago, a young woman named Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed in Chicago; her friends began wearing orange, like hunters wear for safety, in her honor on her birthday in June. A couple of years ago, Bishops Against Gun Violence, an Episcopal group, became a co-sponsor of Wear Orange Day and some of us clergy here in Ohio decided to make and wear orange stoles on the following Sunday. Our decision got press notice and spread to clergy of several denominations all over the country.

Today, after what happened last Sunday in my hometown, I decided to wear my orange stole as a witness to my belief in the need for sensible, strict, and enforceable regulations on gun manufacture and sale, on gun ownership and use. But I am not going to preach about that; I did so after the Sandy Hook school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, after the Mother Emmanuel church schooting in Charlotte, SC, after the Pulse dance club shooting in Orlando, FL. We talk about it and pray about it and preach about it after each incident and nothing changes and there’s nothing left to say. If we didn’t change things after the murders of children, after the murders of a bible study group, or after murders of people out nightclubbing, we aren’t going to change anything after 58 people get murdered (and one commits suicide) in Las Vegas. We just aren’t, and nothing I might say in a sermon will change that.

So . . .

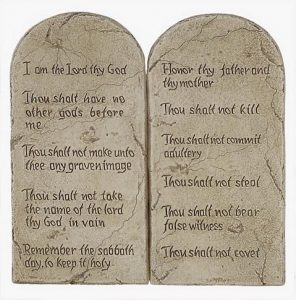

The Big Ten. That’s what we’ve got to consider today, the Ten Commandments. These used to be a regular part of our service of Holy Communion; we said them as a responsive reading at the beginning of the Eucharist. Where I lived and joined the Episcopal Church, that meant we said them once a week, every Sunday; in some other, less “High Church” places, it was once a month. But whatever it was, it was fairly often. Now the Ten Commandments have been made optional. No longer a part of the Communion service, they are part of an optional “Penitential Order” that can be added to the beginning of the service. And, truth be told, they aren’t even a regular part of that Order; they are an option within the option, a “second-order option.” Some ecclesiastical comedians have said that they’ve become “the Ten Suggestions” rather than commandments.

Open your prayer books to page 317, if you would. This is where the optional-optional Decalogue (that’s our fancy Anglican word for the Ten Commandments; it’s Greek and means “ten words” which is, interestingly, what they are called in the Jewish tradition, God’s Ten Words) begins in the older, so-called “Rite One” language. That’s the way I remember saying them every week. The priest presiding at the service would say, “God spake these words, and said” and then he (it was always “he” back then) would recite each commandment and we would respond, “Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.” And so it would go until we got to the last one, the one about coveting, to which we would reply, “Lord have mercy upon us, and write all these thy laws in our hearts, we beseech thee.”

I love our current prayer book and our current liturgy, but I can’t help but wonder if perhaps we haven’t made a mistake relegating the Ten Commandments to an option within an option, something we don’t have to pay any attention to. It’s hard for one’s heart to be inclined toward something one never hears; it’s hard to have something inscribed upon one’s heart that one is never exposed to.

O well . . . . I’m going to shift gears from reminiscing about church to reminiscing about law school.

I had to take a course as a first-year law student, as everyone does, in something called “torts.” It wasn’t about little sweet baked goods, as that name might imply. It was about civil wrongs, the sorts of things you can sue for and get an award of money damages, things like personal injuries or defamation. We had to read a court decision in that course about a lady named Palsgraf. It’s a major decision; it set the standard for something in law known as “proximate cause.”

Mrs. Palsgraf was a passenger waiting to get on a train. While she was waiting, a porter down the platform dropped another passenger’s valise and it made a loud noise; it may even have exploded, if I remember rightly. This set off a series of events something like this: another passenger’s dog was startled by the noise and got loose; the dog jumped on a luggage cart and sent it rolling down the quay; the luggage cart hit a cargo scale, which tipped over; the top of the scale hit Mrs. Palsgraf and injured her. So she sued the railroad company for the negligence of the porter who dropped the bag, saying that that was what caused her injury. The court had to decide whether that was so, or if instead there were too many intervening causes that attenuated the causal link between the porter’s clumsiness and Mrs. Palsgraf’s injury. The court decided that there was no causal link because the porter who dropped the suitcase owed no duty to Mrs. Palsgraf not to drop it, but for our purposes today, it doesn’t matter what the court decided; I want you just to keep that picture in your mind of an almost Rube-Goldberg connection of events, of connection between what a person does and consequences occurring to others.

Or consider this vision of connections. I hesitate to admit that I once participated in drinking games, but I did . . . and you may remember this one, as well, a game that was popular to play in bars a few decades ago, a game called “Six Degrees of Separation.” For some reason, it centered on the actor Kevin Bacon. The idea behind the game was that the theory that anyone on earth can be connected to any other person on the planet through a chain of acquaintances that has no more than five intermediaries. So you’d be given a name and to play the game you had to name the intermediary connections, such as “someone had a spouse, who’d written a book about a woman, who was the cousin of a doctor who’d treated Kevin Bacon’s wife.” It’s another picture of connection between each of us and other people.

So . . . .

Here we have the Big Ten. As the religion of the Hebrews developed, they added more laws to these, subsidiary laws that if you abided by you wouldn’t be in any danger of breaking this big ones. These laws or “mitzvot” (the pural of “mitzvah“) are set out in the five books of Moses; they are the heart of the Torah (what Paul is referring to in today’s epistle lesson when he mentions “the Law”). A medieval scholar named Maimonides counted them up and said there are 613 mitzvot. Around these, then, the rabbis added additional laws or customs of everyday behavior, the sorts of things we think of as “keeping kosher,” which have been described as “a fence around the Torah;” they protect a practicing Jew from violating a mitzvah, which in turn protects him or her from violating one of these ten words of God.

When Paul writes about no longer being required to follow the Law, this is what he is writing about, not about the Ten Commandments, perhaps not even about 613 mitzvot. In today’s portion of the Letter to the Philippians, Paul says that “righteousness under the law” is “rubbish,” that all that matters is the righteousness that “comes through faith in Christ.” We begin to see the theology that he developed more fully in his letter to the Romans, his idea that “a person is justified by faith apart from the works of the law” (Rom 3:28) which Martin Luther used in his argument against the medieval Roman Catholic practice of selling indulgences and which is further developed and often mistakenly preach as some sort of trumping of the Law by grace, that the Law no longer matters, that like the Decalogue in Episcopal worship it has become an option within an option, merely a suggestion. When I hear such preaching, I often wonder, “Have you not heard the words of Jesus: ‘Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill’?” (Mt 5:17) Jesus made it very clear; the Law still stands – “It is easier for heaven and earth to pass away, than for one stroke of a letter in the law to be dropped” before he returns. (Lk 16:17)

The Ten Commandments make it seem easy enough. They are short, easily understood rules: Don’t murder, don’t covet, don’t commit adultery, worship God, honor your parents. It’s all rather simple. And Jesus seemed to make it even simpler when he summarized these rules; he pared them down to just two:

The first commandment is this: Hear, O Israel: The Lord your God is the only Lord. Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength. The second is this: Love your neighbor as yourself. There is no commandment greater than these. (Mk 12:29-31; BCP page 351)

Our bishop has paraphrased that, even, into something that can fit on a bumper sticker: “Love God. Love your neighbor. Change the world.” It sounds so simple.

But is it? No, it’s not. As Paul says in Romans, all sin and all fall short. (Rom 3:23) “No one will be declared righteous in God’s sight by the works of the law; rather, through the law we become conscious of our sin.” (Rom 3:20)

The Ten Commandments, Jesus’ two-part summary, our bishop’s bumper sticker slogan all sound so easy. But Jesus said something else that contradicts that . . .

Remember Jimmy Carter? (Someone in the congregation whispers, “He lusted in his heart . . . .”) Exactly! Jesus said about the Commandment against adultery that one violated it simply by thinking about it! “I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” (Mat 5:28) And he said something similar about the proscription against killing: “if you are angry with a brother or sister,” you’ve violated it! (Mat 5:22) The thing about that Ten Commandments (and all of the mitzvot, frankly) is that we can’t keep them; we are guaranteed to fail. The Hebrews knew that!

When Moses came down from Mt. Sinai with the Ten Words inscribed on stone tablets, the Hebrews took one look at them and were terrified: “They were afraid and trembled and stood at a distance.” (Exod 20:18) They knew they couldn’t live up to them. “We can’t deal with God,” they said to Moses. “You go do that for us.” They knew that failure was guaranteed. We should know it, too.

Which brings me back to proximate cause and Mrs. Palsgraf and six degrees of Kevin Bacon and Las Vegas.

Let me ask you if you know one more name, the name of Menno Simons? Simons was a Dutch Catholic priest in the 16th Century who became a leader of the Reformation. Among the many things he taught was the idea that if we swear allegiance to a nation state that permits (or worse orders) the killing of others, we share in responsibility for such deaths; if we are part of a society which makes it easy (or worse necessary) to kill others, we share in responsibility for such deaths. Some of his followers are called by his first name; they are known as Mennonites. They are pacifists and refuse to carry weapons, to join the military, or to fight in wars. Their stricter theological cousins originating from Switzerland are the Amish, some of whom refuse to even acknowledge citizenship in a nation state.

The Amish/Mennonite position is that we are all the porters on the train platform and that any action of ours that may contribute even in a distant and attenuated way to the injury of others, to the many Mrs. Palsgrafs around us, is a violation of God’s law, of the Second Great Commandment, of one or more of the Big Ten. Though in their strictest communities they hold themselves apart from the world around them, their theology is that the Kevin Bacon game is entirely correct, that we are all connected with very few degrees of separation between us.

We commit adultery simply by thinking of it, said Jesus. We commit murder simply by allowing ourselves to become angry, he said. We are responsible for murders committed by others simply because we are part of a society which enables the commission of murder, say the Mennonites. We cannot help but violate the Commandments, wrote Paul. We are intimately connected with very few degrees of separation to what happened on Sunday night.

My wife and I know people directly involved in dealing with that awful event in Las Vegas. Good friends who are now ministering with and among those injured, with and among those who responded to the scene, with and among those who are mourning the dead and caring for the wounded. She and I are separated from it by only one degree, but I am willing to bet that everyone in this church today can find a Kevin-Bacon-like connection of six degrees or fewer in separation to that tragedy, to every mass killing that has occurred in this country (and for the past five years there has been a multiple firearm homicide on nine out of every ten days on average; see The Guardian). I hope that none of us has actually violated the Commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” but I can guarantee that we are connected to its violation.

“Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law,” we used to regularly pray. “Lord have mercy upon us, and write all these thy laws in our hearts, we beseech thee.” Not because we thought we would be any good at keeping them. Like the Hebrews, we knew we couldn’t keep the rules by ourselves; like the Hebrews, we were terrified of the rules. In the words of our opening collect today, the recitation of the Ten Commandments and our prayers in response reminded us of “those things of which our conscience is afraid.”

No . . . we recited the Ten Commandments because beside the guarantee that we can’t keep them there is another guarantee: that we are forgiven. We have faith that God has “reconciled us to himself through Christ” (2Cor 5:18) and through this faith we do not “nullify the law . . . Rather, we uphold the law.” (Rom 3:31) Our task is to live out God’s forgiveness and thus uphold the Law in that way, with our hearts inclined to obedience of the Commandments written thereon.

They are not “suggestions.” Despite our liturgical changes, they are not second-order (or even first-order) options. In truth, they aren’t commandments, either. They are, as the rabbis call them, ten words, ten basic and fundamental words by which to live our lives, ten words summarized so simply by the Word of God: Love God, love your neighbor. No orange stole that I may wear and nothing I say in a sermon will ever change anything, but if we do that – love God and love our neighbors (all the Mrs. Palsgrafs and all the Kevin Bacons however distant) – all of us together can and will change the world. Amen.

====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the 18th Sunday after Pentecost, October 8, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service, RCL Proper 22A [Track 1], are Exodus 20:1-4,7-9,12-20; Psalm 19; Philippians 3:4b-14; and St. Matthew 21:33-46. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Leave a Reply