In Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe’s novel of post-colonial political intrigue in Africa, Anthills of the Savannah (1987), one of the characters (echoing Karl Marx’s famous aphorism about religion) opines:

In Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe’s novel of post-colonial political intrigue in Africa, Anthills of the Savannah (1987), one of the characters (echoing Karl Marx’s famous aphorism about religion) opines:

Charity . . . is the opium of the privileged, from the good citizen who habitually drops ten kobo from his loose change and from a safe height above the bowl of the leper outside the supermarket; to the group of good citizens (like youselfs) who donate water so that some Lazarus in the slums can have a syringe boiled clean as a whistle for his jab and his sores dressed more hygienically than the rest of him; to the Band Aid stars that lit up so dramatically the dark Christmas skies of Ethiopia. While we do our good works let us not forget that the real solution lies in a world in which charity will have become unnecessary.

For many years, nearly all of my life as a parish priest, every time the story of Christ the King separating the sheep and the goats, Matthew’s picture of the judgment at the end of time, rolls around, I have read it, understood it, and preached it as Jesus’ admonition to us to be charitable. I have read it as an instruction in favor of individual charity, and so novelist Achebe’s statement, his condemnation of charity as “the opium of the privileged,” pulls me up short and discomfits me.

But this week, reading the Gospel lesson again, I focused on the words “All the nations will be gathered before him . . . .” and I had an epiphany! I realized that the parable of the sheep and the goats is not about individuals or individual charity, at all. It’s about nations and I realized that the African novelist’s observation is spot-on.

The original Greek word is ethnoi from which we get our word ethnic. In the classical Greek, the word was used to describe outsiders, someone not of one’s polis (city-state); those outsiders might be other Greeks from some other city or they might be barbarians. Whatever. They were decidedly not one’s own people.

When Greek-speaking Jews translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek, they used this word to translate the Hebrew word goyim (Gentiles); so it came to mean, for them, the non-Jewish nations. The early Christians, being originally a subset of the Jews, took over this meaning, and used it both in this sense and in a more restricted sense to mean groups outside the church.

This was where the use and understanding of this word stood when Matthew wrote his gospel. When he tells this story of Jesus describing the Last Judgment, Matthew’s Jesus uses this word meaning “non-Jewish groups” or “groups outside the church.”

The Son of Man enthroned as king of glory will have “all the nations” –– not “all Christians” –– “gathered before him,” and “he will separate them.” Our NRSV Lectionary text renders this as “he will separate people” but the Greek only says “them.” The addition of “people” to the text is a translators’ decision and, I think, it may not have been a good one. I believe the word “them” refers to the gathered nations as groups, not to individuals as the word “people” implies.

Because of that implication and the way in which this passage has often been preached, we have been conditioned to read this text as instruction for our personal, private spiritual lives, rather than applying its core message to our public, shared life. Our leaders and our politicians like to insert Christian touches, a few symbols or words here and there, referring to our faith in their speeches, but this gospel vision requires more. It calls us to shine the light of the gospel mandate on the laws and systems they (with our votes and our support) have put in place.

Certainly, as individuals, we are called to do the things Jesus mentions (visit the sick, feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and so forth) and he clearly anticipates that his followers will do such things just as he did. However, the question that Matthew’s Jesus handles in this vision is not about the charitable giving, the individual ministries, or the ethics of the church or of Jesus’ disciples, but the response to “the least of these” on the part of nations, of larger societies as a whole.

I think this reading is supported by the gradual psalm the Lectionary has paired with the gospel lesson today.

Be joyful in the Lord, all you lands; *

serve the Lord with gladness

and come before his presence with a song.

. . . reads the first verse of Psalm 100. “All you lands” –– all you countries, all you territories, all you nations, not all you individual persons –– “come before his presence.” Just as in the gospel allegory all the nations gather before the King, the Son of Man, so in the psalm all the lands are called to enter God’s gates with thanksgiving and praise.

Thus, in Matthew’s allegory of the final judgment, the issue is not whether you or I as persons, you or I as church members, you or I as individual Christians visited the sick, fed the hungry, etc. etc. etc. . . . . It is, rather, do we participate in a society which has policies favoring these groups: Does our nation have policies that provide health care to the sick? Does our nation have policies that encourage freedom for prisoners? Does our nation have policies that facilitate the clothing of the naked, housing of the homeless, feeding of the hungry? That’s the question for the ethnoi, for the nations gathered before Christ the King.

The question for us as Christians is, “What have we (as individuals and as the church) done to influence our society, to reform our society so that it lives up to the example of the sheep?” Our brothers and sisters in the United Church of Christ, in their current hymnal, have a modern text entitled Standing at the Future’s Threshold (The New Century Hymnal, 1995, #538) penned by hymnist Paul R. Gregory in 1985. The first two verses speak to this:

Standing at the future’s threshold, grateful for God’s guiding hand,

Asking no protected stronghold, called to be a pilgrim band,

Seeking ever for new vision of the gospel for our day,

We move forward in God’s mission with our faith to show the way.Midst the teeming cities’ millions, witness to God’s boundless love,

Reaching for each system’s lost ones, seeking justice with each move;

Grant us courage, strength, and patience to contend with vicious power,

Lead us forward in the faith that gives us hope in testing’s hour.

Have we, as the hymn says, reached into the system seeking the lost? Have we contended with the “vicious power” of systemic injustice? Have we influenced our society by moving “forward in God’s mission with our faith to show the way?”

Our individual works of charity are good, but they are not what this vision of the Last Judgment addresses. Matthew’s vision is not of a judgment of individual ministries; it is a judgment of societal, national priorities and of social reform. As novelist Achebe’s character reminds us, “While we do our good works [of charity] let us not forget that the real solution lies in a world in which charity will have become unnecessary.”

In presenting his first audience and us with this vision of a shepherd tending his animals, Jesus is reaching back into the rich store of Israel’s prophetic tradition, including the image cast by the prophet Ezekiel in our first lesson today. Jesus longs for that time when, as God speaking through the prophet says, the strayed will be brought back, the injured will be bound up, the weak will be strengthened, and all will be fed with justice; even more he longs for a world where the flock will no longer be scattered or ravaged and where such works of “charity will have become unnecessary.”

So then the question for us is, “What is the lesson in this parable for the church?” I would suggest that it is (to draw on another gospel metaphor) to be the yeast or leaven within the nations influencing, encouraging, and leading them to the sought-for behaviors, leading them to be the societies, the “nations” judged among the sheep. How do we do this?

In a Facebook conversation about this passage, my friend and colleague Sarah Dylan Breuer pointed out that Jesus and the early Christians would not have seen themselves as having any power to influence government, since they were a minuscule minority living in territories occupied by a foreign empire. Christians, however, did see their communities as transcending the traditional ethnic and societal boundaries between peoples to form an alternative social order, creating pockets in which God, not the emperor or any other political figure, reigned. We, living in the modern world, have the ability to do both. We are called to be leaven such that the ethnos within which we find ourselves becomes more responsive to the needs of poor, sick, homeless, and so forth, and we can do that by influencing government through our votes and our communication with elected officials, and by being a community of alternative social order and influencing the society by example. As my colleague put it, “Those of us who are citizens in a democracy are being gravely irresponsible in our stewardship of power and privilege if we do not both seek justice for the poor via civic means and create pockets of community in which justice and mercy are practiced consistently.” Jesus’ disciples are to imagine, and then lead their nations in building, that society in which God’s flock will no longer be scattered or ravaged, that better kingdom which incarnates Christ the King’s own vision of healing, justice, and mercy, that better world “in which charity will have become unnecessary.” (Sarah Dylan Breuer, Facebook comment, November 25, 2017)

I close with the fourth verse of Mr. Gregory’s Standing at the Future’s Threshold as a prayer that we would learn and embody the lesson of the sheep and the goats:

Building justice as the bulwark of the peace that God would give,

Making sacrifice the hallmark of the life we’re called to live:

Grant us, God, to bear our witness to this peace in Christ, and move

Forward with our faith’s own access to the life of hope and love.

Amen.

====================

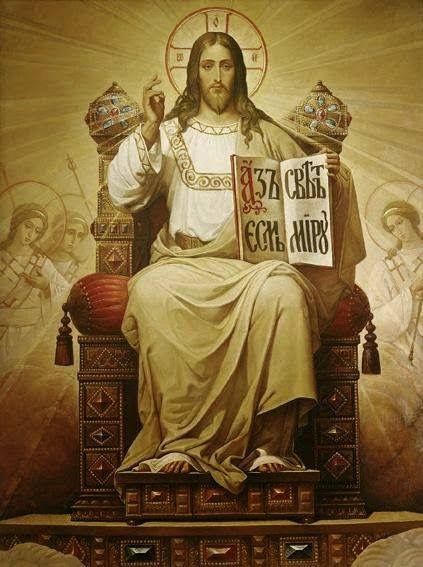

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Feast of Christ the King, November 26, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service, Proper 29, RCL Year A, are Ezekiel 34:11-16,20-24; Psalm 100; Ephesians 1:15-23; and St. Matthew 25:31-46. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Excellent sermon, it crystallizes my thoughts and I thank you for your careful and thoughtful use of scripture in your sermons.

Compelling and convicting. The Achebe quote is powerful and not easily tamed. On Christ the King I always think of what Clarence Jordan asked and answered over fifty years ago: “What’s the biggest lie told in America today?” –– “Jesus is Lord.”

I’d not heard the Jordan quote, Jim. That’s really convicting!

Outstanding work with the text(s), Eric. It exhibits both wrestling and reflection.

Thanks, Bob!