Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,”[1] the Feast of the Transfiguration.

Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,”[1] the Feast of the Transfiguration.

The church’s understanding of the meaning of the event described by Luke in today’s gospel lesson is summarized in today’s opening collect: “[O]n the holy mount [God] revealed to chosen witnesses [God’s] well-beloved Son, wonderfully transfigured, in raiment white and glistening.” The collect expresses the church’s hope that Christians “may by faith behold the King in his beauty.”[2] The Collect for the Last Sunday after Epiphany, on which we also read about this event, similarly summarizes the event as the revelation of the Son’s “glory upon the holy mountain,” and expresses the hope that the faithful may be “changed into his likeness from glory to glory.”[3]

In other words, the Transfiguration is all about Jesus, but, while that’s true, nothing about Jesus is ever all about Jesus! It’s about Jesus to whose pattern his followers are to be conformed,[4] so it is about us, as well. And, as any story is about not only its protagonist but also about the “bit players” who surround him, it is about James and John and Peter, who represent us.

So the question I’d like to explore this morning is not what we learn from the Transfiguration about Jesus, but what we learn about ourselves from this mountain-top experience.

A couple of years ago, during the Covid pandemic lockdown of 2020, I read this book, When Things Fall Apart by Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön.[5] In it, I found some words which, though written from a Buddhist perspective, help to me understand the story of the Transfiguration and its aftermath:

Spiritual awakening is frequently described as a journey to the top of a mountain. We leave our attachments and our worldliness behind and slowly make our way to the top. At the peak we have transcended all pain. The only problem with this metaphor is that we leave all the others behind — our drunken brother, our schizophrenic sister, our tormented animals and friends. Their suffering continues, unrelieved by our personal escape.[6]

This paragraph describes the experience of James, John, and Peter in our gospel lesson, the experience that Jesus would not let Peter memorialize and try to perpetuate by building “dwellings.” Jesus knew that they had “left all the others behind,” and that they would have to return to the drunken brothers, the schizophrenic sisters, and all the others tormented and suffering. Indeed, that is exactly what they did when they came down the mountain. As Luke continues the story, they found other disciples (the rest of the Twelve and perhaps others) unable to cure an epileptic boy whose father had brought him to them:

On the next day, when they had come down from the mountain, a great crowd met him. Just then a man from the crowd shouted, “Teacher, I beg you to look at my son; he is my only child. Suddenly a spirit seizes him, and all at once he shrieks. It convulses him until he foams at the mouth; it mauls him and will scarcely leave him. I begged your disciples to cast it out, but they could not.”[7]

Of course, Jesus can and does.

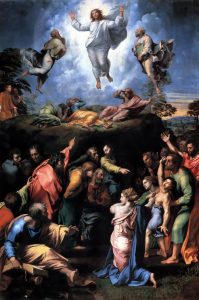

My favorite artistic depiction of the Transfiguration is one by the High Renaissance painter Raphael; it’s a sort of vertical diptych. The top of the painting portrays the glory and radiance of the mountaintop event, while the bottom shows what’s happening down below. Just as the top of Raphael’s painting captures the splendor of the Transfiguration, the bottom captures the tragic need and suffering of this man and his son, and the powerless confusion of the disciples unable to cure the boy. Raphael poignantly captures the contrast between, and the essential connection of, the shining mountaintop and the “valley of the shadow of death,”[8] the differing experiences of human existence: joy and suffering, righteousness and sin, success and failure.

God incarnate in Jesus Christ shares these with us. Jesus, fully God and fully human, celebrates with us on the mountaintops of triumph and weeps with us in the deep valleys of sorrow. Jesus the Son of God knows that, in this life, any escape from “our attachments and our worldliness” is, at best, temporary, and that we must come down from the mountain top into those deep valleys. James, John, and Peter are favored in their participation in the Transfiguration event, brief and transitory though it is. They alone are selected by Jesus to accompany him on the mountain top while the others are denied the experience. But even so, even for them it must end.

This has happened before and it will happen again. James and John and Peter are a sort of triumvirate of the community of apostles, an inner circle on whom Jesus seems to rely and with whom he “pals around.” Not only are they at the Transfiguration, they were present at the raising of Jairus’ daughter[9] and they will be at the top of Mount Olivet as Jesus prepares to enter Jerusalem.[10] They will also help to prepare for the Passover,[11] and they will be in the garden at Gethsemane.[12] They are the privileged among the disciples.

What they witness and experience, however, can be understood as a lesson in rejection of that privilege. In addition to their own favored status, they witness the presence of Moses and Elijah, traditionally understood to represent the Law and the Prophets, the established authority of Judaism, the epitome of cultural and religious power and privilege among the Jews. Jesus associated with them becomes “dazzling,” overwhelmingly bright and overwhelmingly powerful. Jesus’ mission and the renewal of Judaism could have proceeded from there; the Transfigured Jesus could have come down from that mountain, entered Jerusalem, and taken over – bright, powerful, and clearly divine – his entry into the city would have been truly triumphant.

Can you imagine what a scene that would have been? Jesus accompanied by the heavenly representatives of cultural and religious privilege, himself a descendant of David and thus representative of political power, and served by his trusted advisors – his steady rock Peter and the “sons of thunder” given places at his right and at his left – elevated from the life of working-class fishermen to a privileged status of leadership. Jerusalem and all of Judaea would have been his for the taking.

But Jesus had rejected political power when it was offered by Satan[13] and he does so again now by proceeding along a different path to Jerusalem. His Transfiguration on the mountain top and what comes after is, thus, a lesson in the rejection of privilege; Jesus will not allow it to become institutionalized and thus systemic.

It is, I admit, simplistic and facile to draw this analogy, but here it is: in the Transfiguration Jesus demonstrates and then abandons a dazzling white privilege. He could have it, but he chooses not to embrace or exercise it. He rejects it and he insists that Peter, James, and John eschew it, as well. They must join their brothers and sisters at the foot of the mountain and, together with them, accompany him on the journey into the insecurity, pain, and sacrifice of the Crucifixion, into and through what Buddhists call bodhicitta – an altruistic intention to liberate all living beings from suffering.[14] It is only found when advantage and privilege are abandoned. Pema Chödrön calls it “the love that will not die.” She writes:

In the process of discovering bodhicitta, the journey goes down, not up. It’s as if the mountain pointed toward the center of the earth instead of reaching into the sky. Instead of transcending the suffering of all creatures, we move toward the turbulence and doubt. We jump into it. We slide into it. We tiptoe into it. We move toward it however we can. We explore the reality and unpredictability of insecurity and pain, and we try not to push it away. If it takes years, if it takes lifetimes, we let it be as it is. At our own pace, without speed or aggression, we move down and down and down. With us move millions of others, our companions in awakening from fear. At the bottom we discover water, the healing water of bodhicitta. Right down there in the thick of things, we discover the love that will not die.[15]

That love cannot be found on the mountain top of privilege. It can only be found by going to the valley floor of solidarity with the poor and the disadvantaged, only by feeding the multitudes and tending to their needs, and then by going deeper, to the very core of suffering. It is there that we find, in Pema Chödrön’s words, “the healing water of bodhicitta,” or as Jesus put it, “water gushing up to eternal life.”[16]

In Christian tradition, the mount of Calvary is the omphalos or navel of the earth, the legendary center of the world: the Cross is Chödrön’s “mountain pointed toward the center of the earth.” The Crucifixion is the descent into “turbulence and doubt,” into “the reality and unpredictability of insecurity and pain.” It is the ultimate rejection of privilege, and in it is revealed “the love that will not die,” the love which rose on Easter morning.

So, I want to suggest that contrary to the typical interpretation, the Transfiguration of Christ is not meant to be a powerful demonstration of Jesus’ divine nature or a manifestation of the glory which Christ possessed prior to his Incarnation, from before time. Instead, it is an instruction to his disciples, then and now, to reject privilege of any sort. Love and joy are not found in privilege; they are found, as Pema Chödrön puts it, “in the thick of things.”

The whole of the Transfiguration event, not just the vision of the Transfigured Christ, but also (and more importantly) what takes place afterward, teaches us that we, like Jesus, may not go up to joy until first we suffer pain,[17] and may not enter into glory before we experience the truth of the Crucifixion. It is only by walking in the way of the cross, not by ascending to the mountain top, that we find the way of life and peace, and the love that will not die.[18]

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Feast of the Transfiguration, August 6, 2023, to the people of Church of the Ascension, Lakewood, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest preacher.

The lessons were from the propers for the Transfiguration: Exodus 34:29-35; Psalm 99; 2 Peter 1:13-21; and St. Luke 9:28-36. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

The illustration is Raphael’s “The Transfiguration” (1516-20) on display in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] The Calendar of the Church Year, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 16

[2] The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 243

[3] Ibid., page 217

[4] Romans 8:29

[5] Pema Chödrön, When Things Fall Apart, Anniversary Edition (Shambhala Publications, Boulder, CO: 2016)

[6] Ibid., page 92

[7] Luke 9:37-40 (NRSV)

[8] Psalm 23:4 (KJV)

[9] Mark 5:37; Luke 8:51

[10] Mark 13:3

[11] Luke 22:8

[12] Matthew 26:37

[13] Luke 4:5-7

[14] Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Mother Teresa and the Bodhisattva Ideal: A Buddhist View, Claritas: Journal of Dialogue and Culture, Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2012), 96, 101

[15] Chödrön, op. cit., page 92

[16] John 4:14 (NRSV)

[17] Collect for Monday in Holy Week, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 220

[18] A Collect for Fridays, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 99

Leave a Reply