“Name this child.” That’s what I say to parents of infant baptismal candidates as I take their children from them. The words are not actually written in the baptismal service of The Book of Common Prayer as they are in some other traditions’ liturgies, but there is a rubric that says, “Each candidate is presented by name to the Celebrant . . . .”[1] so asking for the child’s name is a practical way of seeing that done. It’s practical, but it’s also a theological statement.

There is a common religious belief found in nearly all cultures that knowing the name of a thing or a person gives one power over that thing or person. One finds this belief among African and North American indigenous tribes, as well as in ancient Egyptian, Vedic, and Hindu traditions; it is also present in all three of the Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The naming we do at baptism echoes the naming that takes place in Judaism when a male infant is circumcised on the eighth day after his birth. In that service, called the brit milah or bris, the officiating mohel prays, “Our God and God of our fathers, preserve this child for his father and mother, and his name in Israel shall be called ________”[2] and the prayer continues that, by his naming, the infant will be enrolled in the covenant of God with Israel. A similar thing is done when a girl is named in the ceremony called zeved habat or simchat bat, the “gift (or celebration) of the daughter” on the first sabbath following her birth.[3] With the name given at baptism, the church says to its newest member, “This is who you are: washed in the waters of baptism, sealed by the Holy Spirit, and marked as Christ’s own forever,”[4] a brother or sister in the church, a fellow member of the Body of Christ, an adopted child of God the Father.

Continue reading

What does it mean to say “Jesus is Lord”? The question arises because of today’s dialog between Jesus and some of the Pharisees about the relative importance of the Commandments. Jesus responds to a lawyer’s question about the greatest commandment and then follows his response with a question about the lordship of the Messiah, the anticipated “Son of David.”

What does it mean to say “Jesus is Lord”? The question arises because of today’s dialog between Jesus and some of the Pharisees about the relative importance of the Commandments. Jesus responds to a lawyer’s question about the greatest commandment and then follows his response with a question about the lordship of the Messiah, the anticipated “Son of David.”  “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”

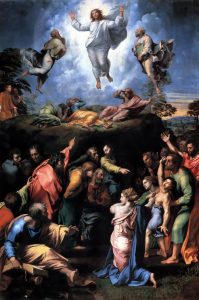

“The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .” Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,”

Today, in the normal course of the Lectionary, would have been the 10th Sunday after Pentecost on which, this year, we would have read the lessons known as “Proper 13” in which the gospel lesson is Matthew’s story of the feeding of the 5,000. However, since this is August 6, we don’t follow the normal course. We step away from the Lectionary to celebrate one of the feasts which, in the language of the Prayer Book, “take precedence of a Sunday,” It’s the last Sunday of the Christian year, sort of a New Year’s Eve for the church. We call it “the Feast of Christ the King” and we celebrate it by remembering his enthronement. Each year on Christ the King Sunday we read some part of the crucifixion story. As Pope Francis reminded the faithful in his Palm Sunday homily a few years ago, “It is precisely here that his kingship shines forth in godly fashion: his royal throne is the wood of the Cross!”

It’s the last Sunday of the Christian year, sort of a New Year’s Eve for the church. We call it “the Feast of Christ the King” and we celebrate it by remembering his enthronement. Each year on Christ the King Sunday we read some part of the crucifixion story. As Pope Francis reminded the faithful in his Palm Sunday homily a few years ago, “It is precisely here that his kingship shines forth in godly fashion: his royal throne is the wood of the Cross!”

When my nephew, who’s now in his mid-40s, was about six years old, he was given a homework assignment that he found frustrating and he just didn’t want to finish it, but his mother made him sit down and do it rather than something else more to his liking. In his frustration, he blurted out, “I hate you!” My late sister-in-law responded calmly, “That’s too bad because I love you.” After a moment of reflection, my nephew amended his angry outburst: “I love you, too,” he said, “but I don’t like you right now.”

When my nephew, who’s now in his mid-40s, was about six years old, he was given a homework assignment that he found frustrating and he just didn’t want to finish it, but his mother made him sit down and do it rather than something else more to his liking. In his frustration, he blurted out, “I hate you!” My late sister-in-law responded calmly, “That’s too bad because I love you.” After a moment of reflection, my nephew amended his angry outburst: “I love you, too,” he said, “but I don’t like you right now.”