The last sentence of our reading from Genesis says, “And [Abram] believed the Lord; and the Lord reckoned it to him as righteousness,”[1] so this text is often treated as a story of faith. But, in all honesty, this is a story of doubt. It is the story of Abram questioning God’s promise of a posterity; it is a story of tribalism and concern for bloodline, ethnicity, and inheritance.

We humans have a predisposition to tribalism, to congregating in social groupings of similar people. Think about the neighborhood and community where you live; I’m willing to bet that your neighborhoods are made up of people for the most part pretty similar to yourselves. Aside from clearly racist practices like red lining and sundown laws, we modern Americans may not consciously organize ourselves into tribal groupings, but if we look at ourselves honestly we will find that we do. Like attracts like. As individuals, we are initially situated within nuclear families, then as we grow we broaden our social interactions to extended families, then clan, tribe, ethnic group, political party, nation.

It’s genetic: our nearest relatives, the great apes and chimpanzees, demonstrate this same family and clan predilection. And it’s religious: we find it in sacred literatures across cultures. Today’s lesson from Genesis is a case in point.

Come Holy Spirit, Comforter, Spirit of Truth,

Come Holy Spirit, Comforter, Spirit of Truth, A book entitled Stories for the Heart was published a few years ago by inspirational speaker Alice Gray. It is a compilation of what Gray calls “stories to encourage your soul;” one of them is the following story, whose original author she says is unknown. It may not be true, but I (for one) hope it is:

A book entitled Stories for the Heart was published a few years ago by inspirational speaker Alice Gray. It is a compilation of what Gray calls “stories to encourage your soul;” one of them is the following story, whose original author she says is unknown. It may not be true, but I (for one) hope it is: Anthelme Brillat-Savarin , an 18th century French politician once said, “Tell me what kind of food you eat, and I will tell you what you what kind of man are.”

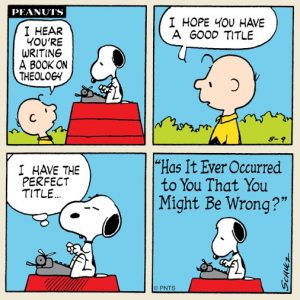

Anthelme Brillat-Savarin , an 18th century French politician once said, “Tell me what kind of food you eat, and I will tell you what you what kind of man are.” Christology is one of those odd words of the Christian tradition that one doesn’t hear much in church but which one hears a lot in academic circles. Christology is defined as “the field of study within Christian theology which is primarily concerned with the ontology and person of Jesus as recorded in the canonical Gospels and the epistles of the New Testament.”

Christology is one of those odd words of the Christian tradition that one doesn’t hear much in church but which one hears a lot in academic circles. Christology is defined as “the field of study within Christian theology which is primarily concerned with the ontology and person of Jesus as recorded in the canonical Gospels and the epistles of the New Testament.” Our gradual this morning asks a question of God about human existence:

Our gradual this morning asks a question of God about human existence: For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.

For recreational reading these days, I’m into a novel entitled Winter of the Gods.