So, did you make any New Year’s Resolutions? I usually make three: lose weight, get more exercise, eat more healthily. I make them every year and every year by about Valentine’s Day I’ve let them slip. But this year I’m making a different resolution….

I did some research into the custom of making New Year’s Resolutions and here’s what I learned: the people of what’s called “the Old Babylonian Empire” are believed to have been the first people to make New Year’s resolutions; this was around the time of Hammurabi, the king known for his code of law. They celebrated the new year in mid-March, at the spring equinox when crops are planted. During a twelve-day religious festival known as Akitu, the Babylonians made both national and personal resolutions reaffirming their loyalty to the king, recommitting to pay any debts, and promising to return any farm equipment they had borrowed.[1]

From Babylon this custom spread east Persia and beyond. The late University of London historian Mary Boyce suggested that the Babylonian Akitu may be the origin of the Zoroastrian New Year celebration of Nowruz,[2] which is also associated with the start of spring and which Zoroastrians describe as “a time for personal growth, of setting new intentions for the new year.”[3] There is a lovely song which they sing at this time which includes the line “my yellow is yours, your red is mine.” This is a prayer asking that the holy fire take away ill-health and problems, and replace them with warmth, health, and energy.

Historians believe that the Zoroastrian Persians of Cyrus the Great’s Achaemenid Empire introduced the New Year’s Resolution custom to the Greeks (the Athenian historian Xenophon writes about New Year celebrations at Persepolis the capital of the Persian empire in 6th Century BCE)[4] and from the Greeks it was adopted by the Romans. When Julius Caesar reformed the calendar and moved the start of the year from the equinox to the beginning of January in 46 BCE, the New Year’s Resolution custom moved with it. And more than two millennia later, we’re still doing it.

“Well,” you’re probably thinking, “that’s interesting, but what does it have to do with the Second Sunday of Christmas and the Bible readings for today?” OK, let’s take a look at the Gospel story we heard a few minutes ago, the visit paid by “wise men from the east” to the Holy Family. My maternal grandmother, whose first language was German, would have referred to the feast of Epiphany (this coming Thursday) when we celebrate this event as “Dreikönigstag” or “Three Kings Day,” but we all know that they weren’t kings, and I’m sure we all know that we don’t know how many of them there were, or what their names were, or exactly what they intended their gifts to mean. All of that is the stuff of pious legend and of Christmas carols. In fact, most of what we “know” about this story is stuff Christians have made up to fill in the blanks of ignorance and this made-up stuff blinds us to what we really do know, or at least should know.

Even our New Revised Version translation obscures who they were: the term “wise men” is a rather poor translation of the Greek word “magoi” used by Matthew.[5] The New International Version does a better job by not translating it, simply anglicizing it to “Magi.” This Greek word comes from the old Persian word “magupati,” or “mobed” as it has come into modern Farsi,[6] the title given to Zoroastrian priests, a clergy “who were credited [says the Encyclopedia Britannica] with profound and extraordinary religious knowledge.”[7]

I believe that Matthew has included this story right at the beginning of his gospel to make a solid connection between the Incarnation of God in Christ and the revelation of monotheism in that ancient religion, between the teachings of Jesus and the ethics of the Magis’ Zoroastrian faith. And even if that was not Matthew’s intent, it is certainly something that we, as educated and perceptive Christians, should explore. Zoroastrian “ideas lie only vaguely concealed under subsequent Western religious thought from the first century to the present. According to Joseph Campbell, the obscure religion of the Magi … is the primary religious heritage of the Western world.”[8]

In the first chapter of Matthew, the evangelist lays out a genealogy for Jesus that establishes his bona fides as a Jewish messiah in the line of King David, but he does so in a way that underscores the Persian connection brought to life in the visitation of Magi. He sums up the genealogy in verse 17: “All the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations; and from David to the deportation to Babylon, fourteen generations; and from the deportation to Babylon to the Messiah, fourteen generations.”[9] Now the Babylonian exile and its end may simply have been a convenient historical marker, but it’s worth noting, I think, that it was ended through the benevolence of none other than Cyrus the Great, a devout Zoroastrian and king of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia which spread the ancient Babylonian practice of making New Year’s Resolutions!

Why might Matthew’s Gospel make this connection between Jesus and Zoroastrianism? It might be because in that faith we find one of the earliest formulations of an ethic which would become a central tenet of Jesus’ teaching. As set forth by Zarathustra himself, quoted in many Zoroastrian texts: “Do not to others what ye do not wish done to yourself; and wish for others, too, what ye desire and long for, for yourself. This is the whole of righteousness, heed it well.”[10] Matthew would later report Jesus teaching this same precept: “In everything do to others as you would have them do to you,”[11] he says in the seventh chapter. Or, more simply, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”[12]

The Zoroastrian concept of loving oneself is that human beings are “expected to understand their importance in the hierarchy of the world, never take themselves lightly, avoid abstinence and self-derogatory attitudes, and to constantly try to preserve their dignity.”[13] A central maxim of the faith is “Good Thoughts. Good Words. Good Deeds. Do the right thing because it is the right thing to do.”[14] From this flows the Zoroastrian understand of the purpose of life: “To be among those who renew the world… to make the world progress towards perfection.”[15] Matthew’s Jesus would preach a similar message in the Sermon on the Mount, proclaiming the Beatitudes, instructing his followers to love their enemies and pray for the persecutors, and concluding with the admonition, “Be perfect … as your heavenly Father is perfect.”[16]

One modern text summarizes the principles of the Magis’ faith this way:

Think creatively, constructively, rationally, originally and independently with your head; love fully, universally and joyously with your heart; and live dynamically in total goodness by using your hand to serve [humankind] in the cause of unity and peace.[17]

I think Matthew’s Gospel links Jesus’ genealogy to the Zoroastrian liberation of the exiled Jews and then tells the story of the Magis’ visit to encourage us to see a connection, a continuity between these ethical teachings and the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

If you haven’t made your New Year’s Resolutions yet, perhaps meditating on these principles of the Magis’ faith will give you some guidance.

Before I end, I want to pay tribute the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu who died on Christmas Day. He was a great example and role model for all persons but especially for us who share his Anglican faith. The former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams in his 2016 book Being Disciples: Essentials of the Christian Life wrote this about Tutu:

When I think of people in my own life that I call holy, who have really made an impact…[these] people have made me feel better rather than worse about myself. Or rather, not quite that: these are never people who make me feel complacent about myself, far from it; they make me feel that there is hope for my confused and compromised humanity…somehow, I feel a little bit more myself…I have a theory, which I started elaborating after I had met Archbishop Desmond Tutu a few times, that there are two kinds of egotists in this world. There are egotists that are so in love with themselves that they have no room for anybody else, and there are egotists that are so in love with themselves that they make it possible for everybody else to be in love with themselves…And in that sense Desmond Tutu manifestly loves being Desmond Tutu; there’s no doubt about that. But the effect of that is not to make me feel frozen or shrunk; it makes me feel that just possibly, by God’s infinite grace, I could one day love being Rowan Williams in the way that Desmond Tutu loves being Desmond Tutu.[18]

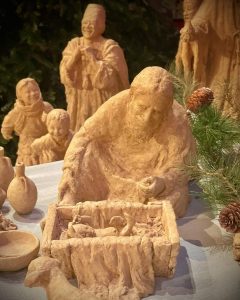

And here’s a bit of a tie-in to today’s Gospel: the Washington National Cathedral’s official Nativity crèche was created in 1994 by Barbara Hughes, an artist who went to the National Cathedral School. The crèche shows a joyful scene of the Holy Family surrounded by shepherds and animals, by townspeople, and by the visiting Magi. Everyone is smiling and one of the Magi is clearly laughing; that figurine bears the face of Desmond Tutu.[19]

Remembering the Magi, then, I can think of no better New Year’s Resolution than to strive, with God’s grace, to love being me the way that Desmond Tutu loved being Desmond Tutu!

May you love being you, may you love your neighbor as yourself, and may you help the world to progress toward perfection! Amen and Happy New Year!

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on January 2, 2022, the 2nd Sunday of Christmas, to the people of Harcourt Parish, Church of the Holy Spirit, Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest preacher substituting for the Rev. Rachel Kessler, Rector of the parish.

The lessons read at the service were Jeremiah 31:7-14, Psalm 84, Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19a, and St. Matthew 2:1-12. These lessons are from the Episcopal Church’s version of the Revised Common Lectionary (see The Lectionary Page).

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Pruitt, Sarah, The History of New Year’s Resolutions, History,com

[2] Boyce, Mary, and Frantz Grenet, A History of Zoroastrianism: Under the Achaemenians (Brill, Leiden:1982)

[3] Showkatian, Tahereh, Simple Preparations for Nowruz, Meagan Rose Wilson

[4] Tuplin, Christopher, and Vincent Azoulay, Xenophon and His World (Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart:2004)

[5] Matthew 2:7 NRSV

[6] Herzfeld, Ernst, Zoroaster and His World (Princeton University Press, Princeton:1947)

[7] Magus: Persian priesthood, Encyclopedia Britannica

[9] Matthew 1:17 NRSV

[10] Attributed to Zoroaster in several sources, e.g., Pecorino, Philip A., The Categorical Imperative, Introduction to Philosophy (Queensborough Community College, CUNY:2001), online textbook

[11] Matthew 7:12 NRSV

[12] Matthew 22:39 NRSV

[13] Joshanloo, M., Self-Esteem in Iran: Views from Antiquity to Modern Times, Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 30 Dec 2016, pp. 22-41, 26

[14] Zoroastrianism: The Religion of Good Conscience, Persian Encyclopedia

[15] Zoroaster, Yasna: Sacred Gathas, Hymns of Zarathushtra: With Glossary of Zoroastrian Terms, L. H. Mills, tr. (CreateSpace, Scotts Valley, CA:2016)

[16] Matthew 5:48 NRSV

[17] Zarathushtrianism: An Ancient Faith for Modern Man, English Zoroastrian Library

[18] Quoted in Macintyre, James, Rowan Williams: The Authentic Disciple, Christian Today, 31 August 2016

[19] Good News of Great Joy: An Advent & Christmas Companion for Children & Families, Washington National Cathedral pamphlet, 18 Dec 2020

Leave a Reply