After attending the midweek Eucharist at St. Bartholomew’s Church in Wilmslow, my host Sally M. took me to see the Quarry Bank Mill, one of the largest cotton producers of the English Industrial Revolution. The Mill was founded by Samuel Greg from Belfast, Northern Ireland, and stayed in the Greg Family until 1939 when Alexander Carlton Greg gave the Mill and the family estate to the National Trust. It is now a well-preserved and highly educational historical site encompassing not only the Mill, but the Apprentice House in which young pauper and orphan children who worked in the Mill were lodged, Styal Village where the older workers and their families lived, Quarry Bank House where the Gregs lived next door to the Mill, and Mrs. Greg’s gardens which provided her with enjoyment and fresh vegetables for the children living in the Apprentice House.

I was able only to visit the Mill itself due to lack of time, but hope some day to return and see the rest of the site.

The Mill is a marvel of early industrial technology presented in such a way that the visitor really appreciates the “improvements” in cotton production from the cottage industry it originally was when a woman would spin all day to make enough cotton to work on her loom all day the next day producing about 8 inches of yard-width cloth! The water-wheel and later steam driven machines could turn out yards and yards of thread, yarn, and cloth in a few hours. In addition, there are exhibits about how looms are set up to make patterns and about the way in which patterns not woven into the fabric are printed on it.

I’ll just show a few pictures here and add a few comments.

This is an exhibit showing a spinning wheel in the background and hand-loom in the foreground. A volunteer in period dress explained the way in which these machines were used by women in the cottage-industry days of cotton production.

One of these volunteers is showing the operation of a flying-shuttle loom, an improvement on the hand loom which made the work go faster; this loom also has an improvement which makes it possible to change the threads of the weft so as to add colored stripes or bands to the cloth. The other is setting up a spinning jenny seen in the next picture, a machine with which one woman could produce not just one, but up to 16 bobbins of thread at a time.

These two machines spin yard and thread onto hundreds of bobbins; the third then takes those threads and rolls them neatly onto a drum for use on the mechanized looms as the warp.

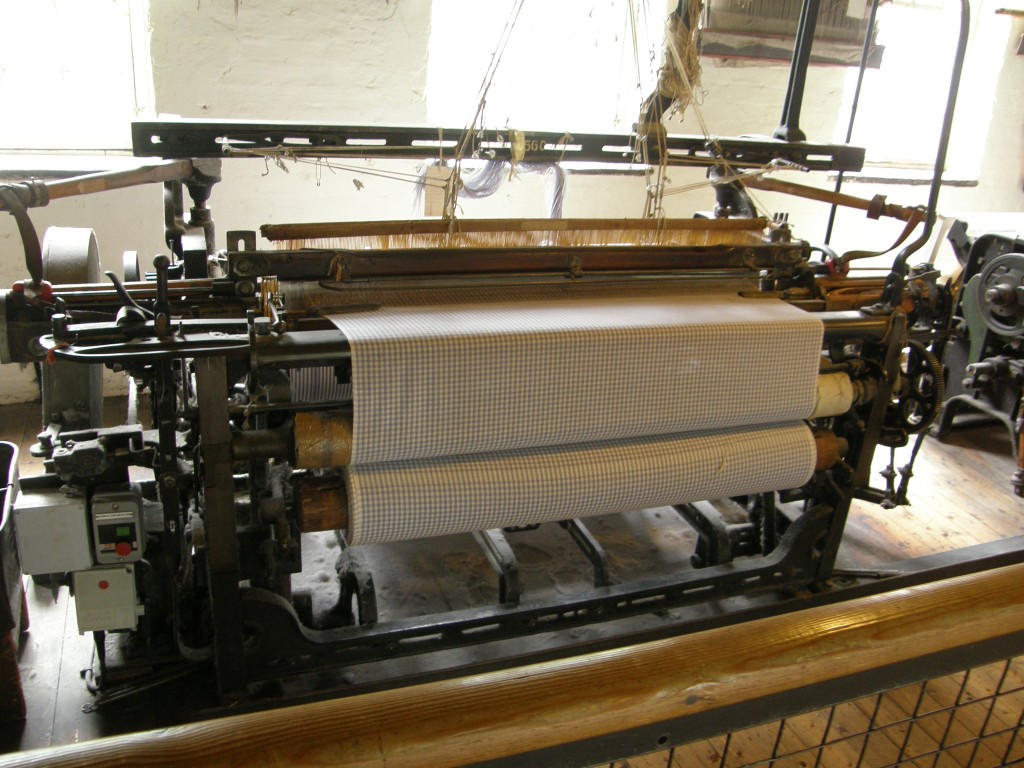

These two machines are individual mechanized looms now run with electrical motors for demonstration purposes.

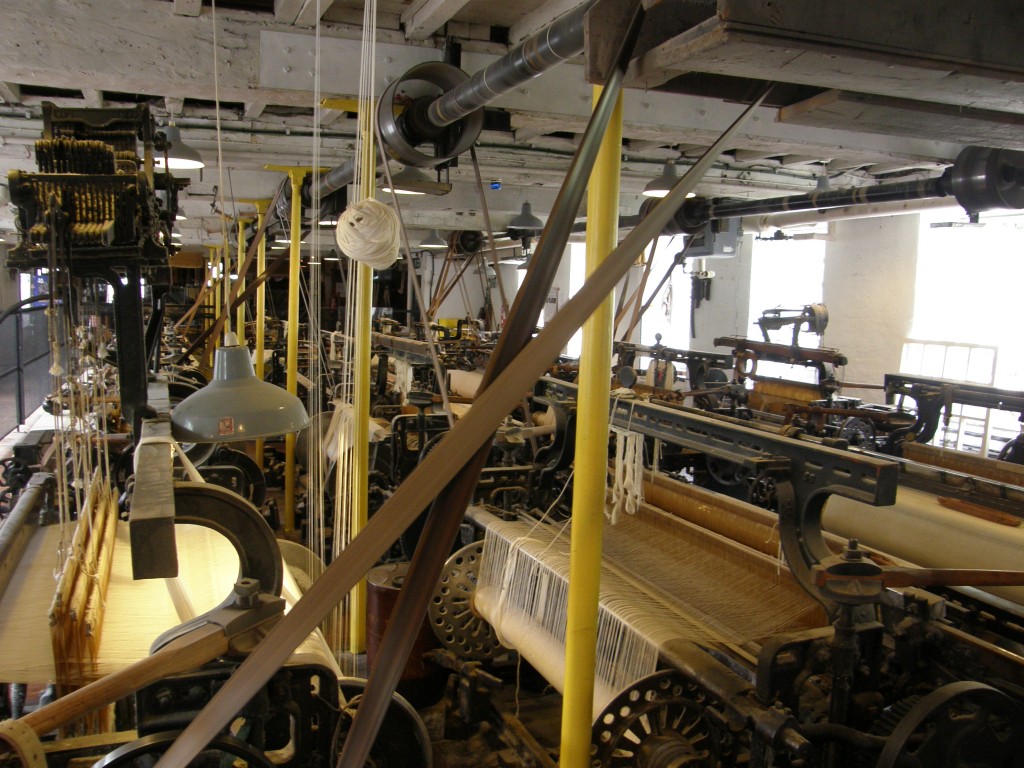

But, of course, the Greg mill didn’t rely on individual machines … a hundred or more machines were set up together, all running off a central power source (either water wheel or steam turbine). One room of the mill is set up to show what this was like and while were there a worker set only three of the machines working – the noise was deafening! I can’t imagine what it must have been like to work there with all of the machines running.

Here is a picture of the several looms together; the next picture is the bank of bobbins which feed the looms.

Men would run the looms; the apprentices (young boys about nine years of age) would go under the looms to clear jams or tie broken threads while the looms were working. As we went through the exhibit, there were several displays telling us about boys who had died from injuries received while working on running machinery.

The last display I want to share in this posting is the display of printed cotton cloth. I thought my daughter, a print maker, would appreciate this pictures of the cylindrical drums used imprint the cloth and the press on which they are used.

The Gregs were enlightened mill operators for their day. They provided fresh food and reasonably good housing for their apprentices, as well as rudimentary education. But let’s face it, the working conditions of the 18th and 19th Centuries were horrendous. One also must face the fact that large scale industrial production of cotton cloth put a vital cottage industry to death and changed an entire society.

Hand weaving of cloth and the making of clothing by hand was a staple activity of Gaelic life, as well as of English life, prior to the Industrial Revolution. In their collections of rustic charms, Douglas Hyde in Connacht in Éire and Alexander Carmichael in the islands and highlands of Scotland both recorded many songs sung by women as they worked the looms or finished the cloth; these songs reflect the rhythm of the looms or, in the case of those sung during group work like the waulking of the cloth, provided a rhythm for unified activity. (Wikipedia has a brief article about Scottish waulking songs.)

However, it was not only in these work songs that the making and working of cloth found its way into the folk songs of the Gaelic people: it was also in their love songs! The following is a song Dr. Hyde collected from Walter Sherlock of County Roscommon (because this post has gotten rather long I won’t record here the Irish, only the English). The title is The Tailoreen of the Cloth. (The ending “-een” or “-ine” added to Irish words means “little”, so in this song treasureen is a way of saying “little treasure”; tailoreen, “little tailor”. Céad fáilte is Irish for “a hundred welcomes”.)

I will leave this village

Because it is ugly,

And I go to live

At Cly-O’Gara?

The place where I will get kisses

From my treasureen, and a Céad fáilte

From my soft, young little dove,

And I shall marry the tailor.Oh, tailor, oh, tailor,

Oh, tailoreen of the cloth,

I do not think it prettier how you cut your cloth

Than how you shape the lies;

Not heavier would I think the quern of a mill,

And it falling into Loch Erne,

Than the lasting love of the tailor

That is in the breast of my shirt.I thought, myself,

As I was without knowledge,

That I would sieze your hand with me

Or the marriage ring,

And I thought after that

That you were the star of knowledge

Or the blossom of the raspberries

On each side of the little road.(From Douglas Hyde, Love Songs of Connacht, page 37)

The many working songs of weaving women and love songs like this reflect a way of life ended by the Industrial Revolution so brilliantly displayed by the Quarry Bank Mill.

what a wonderful tour of the Quarry Bank Mill. The printing drums are very interesting, and the info on the young lads working under the looms.