When I find myself in times of trouble,

When I find myself in times of trouble,

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

And in my hour of darkness

she is standing right in front of me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be[1]

I did not begin this morning with “Happy Christmas” or “Merry Christmas” because, although it’s December 24th, it’s not Christmas; it’s not even Christmas Eve yet! The rest of the world may want you to think it’s Christmas and that it has been since mid-October, but the Episcopal Church insists that it is not yet Christmas. In fact, there’s still more than nine months until Christmas if we believe the good news we just heard from the evangelist Luke! We still have some time to wait for trees and carols and packages, for festive dinners and “chestnuts roasting on an open fire” and the “holy infant so tender and mild.” We still have some of the Advent season to complete and so on this, the Fourth Sunday of Advent, we focus our attention on Mary and consider not the end of her pregnancy, but its beginning, that moment when the Angel Gabriel told her that she had been chosen to be the mother of the Messiah.

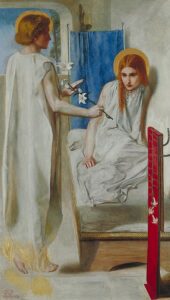

Visual artists depict the stories of the bible in many fascinating ways and their works can help us explore scripture’s meaning. Often their images capture or suggest nuances in a story that we might miss just hearing the words. This morning, I’d like to tell you about three paintings that particularly speak to me about the Annunciation. They are the Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini painted in the 1850s, Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli’s late 15th Century Cestello Annunciation, and a contemporary piece by American artist John Collier.

In Rosetti’s painting, Mary is in bed, suggesting that Gabriel came to her in an hour of darkness. The room is plain and undecorated; it could be anywhere in any era. She is wearing a simple white shift and sitting up in the bed. Her small, rough bed is shoved up against a wall at Mary’s left; Gabriel stands to her right. Mary is shrinking away from the angel, pressing herself against the wall. She has fiery red hair, darkly hooded eyes, and the look on her face is confused, concerned, and almost defiant. Her right hand, resting on the bed covers, is clinched into a fist. The angel’s right hand holds out an Easter lily while his left is extended in a placating gesture, the palm turned down as if trying to reassure the girl.

I love the carol we sang as our Sequence Hymn,[2] but Rosetti seems to be suggesting that, antithetical to its lyric, Mary may not have been gentle and lowly, meekly bowing her head. Quite the contrary, he depicts her as a headstrong and willful young woman to whom Gabriel’s greeting did not initially come as good news! In Rosetti’s painting, the “eyes of flame” are not Gabriel’s; they are Mary’s. Luke describes her as “perplexed”; Rosetti suggests that, as in the Beatle’s song, this was for Mary a “time of trouble.” After all, what intelligent unwed girl of 14 really wants to become pregnant?

Botticelli’s Annunciation is a daytime scene. Mary is portrayed as a Medici princess! She’s all decked out in blue and red Renaissance robes and stands in a beautiful Florentine palace before a window overlooking a Tuscan landscape. Not a very realistic depiction, of course, since she was a First Century Palestinian peasant girl, but that (I think) is the point! Where Rosetti portrays Mary’s eternal nature by placing her in an indistinct setting, Botticelli illustrates her timelessness by portraying her in his contemporary world.

Botticelli’s Virgin, like Rosetti’s, seems to be withdrawing from the angel, holding her hands out as if fending him off. The expression on Mary’s face is nearly unreadable, and while it is not fiery consternation, it is certainly not one of acceptance. As one commentator describes the painting, “Botticelli has depicted [Mary] a moment before she answers Gabriel, she is actually trapped in a kind of eternal limbo of hesitation, unsure of how to react, or whether to accept her calling.”[3] American poet Andrew Hudgins says that “Botticelli, in his great pity, lets [Mary] refuse, accept, refuse, and think again.”[4]

Botticelli’s Gabriel is kneeling before Mary in an attitude of supplication. His left hand holds a stock of Easter lilies resting on his shoulder while his right hand reaches out to Mary as if he is pleading with her. The expression on his face is one of distressed apprehension. You can almost hear him thinking, “Oh, no! She’s going to refuse! I’m going to have to go tell the Boss that I blew it!”

Although Botticelli’s Mary is older than Rosetti’s, a young adult rather than an innocent teen, both artists depict the Virgin as a woman with personal agency, as an individual able to control her own life. These artists insist that Mary had a choice, that the decision to become pregnant, to carry God’s child to term, and to give birth to the Savior is hers and hers alone. They seem to be saying, in the words of Baptist pastor Jeremy Richards,

[C]an we just take a minute to notice that before the Creator-God of the universe . . . impregnates Mary an angel shows up and checks with her to make sure she’s on board. …[T]he God of the universe asks permission before touching a woman’s body …. God waits for Mary’s yes.[5]

Somewhat more poetically, contemporary English poet Malcolm Guite makes the same point in his Sonnet for the Annunciation:

[O]n this day a young girl stopped to see

With open eyes and heart. She heard the voice;

The promise of His glory yet to be,

As time stood still for her to make a choice;

Gabriel knelt and not a feather stirred,

The Word himself was waiting on her word.[6]

As St. Anselm of Canterbury preached, “He who could create all things from nothing would not remake his ruined creation without Mary.”[7] Mary had personal agency; the decision was hers.

This is why the Roman Catholic dogma of the Immaculate Conception makes no sense to me. This dogma teaches that Mary was conceived without the stain of Original Sin, “saved from sin … in a different and more glorious way than the rest of us are.”[8] It asserts that Mary was “prepared” from before her conception (as my Aunt Mabel would have said, “before she was a twinkle in her father’s eye”) to be holier than any other human being, a more appropriate “vessel” for the incarnation of the Son of God, a “living tabernacle,”[9] a new Ark of the Covenant.[10] It seems to me that it says that Mary was not really a person but an object which only appeared to be an ordinary woman. If she was thus set apart from all other women (and all men, for that matter), then Mary was also set up, deprived of free will and not given any choice at all.

But God doesn’t work that way! God created human beings with freedom, agency, and choice. God’s nature is love, “uncontrolling, non-coercive love. God can’t violate His own nature. God would not be God if He controlled or coerced [anyone’s] free will.”[11] And God certainly wouldn’t do that to the mother of God’s only begotten Child!

Rosetti’s and Botticelli’s paintings of Mary highlight her identity with other human beings in all times and places, not her difference from us, and it is that which makes her important. Mary is a model of faith because she doesn’t merely accept, she chooses and actively agrees to the role God invites her to play. She is extraordinary not because she is immaculate or in some way holier than the rest of us. Mary should be venerated not as an exception, but rather as an exemplar, as the example of what can happen, of what should happen with anyone who believes in the God of freedom. Mary’s words of wisdom, “Let it be,” are not a resigned sigh of submission; they are her assertion of personal agency, her claim on the right to make her own decisions, her declaration of independence.

Last week, the Anglican Diocese of Brisbane, Australia, installed its new archbishop, the Most Rev. Jeremy Greaves. In his inaugural sermon he said:

Christian hope invites those under its influence to see possibility in everything — nothing, not even the deepest darkness, is outside the possibility of transformation. * * * It seems to me that we have a choice in this season… — we can continue to bow down in fear before the many idols we’ve created or we can help one another learn to walk in the dark.[12]

In our hour of darkness (to paraphrase the Beatles) Mary is standing right in front of us, speaking her words of wisdom, “Let it be,” encouraging each of us to make our choice, to agree to our calling whatever it may be. The English mystic Evelyn Underhill said that Christ is born “in our souls for a purpose beyond ourselves. *** And … we have got to get on with it, be useful.”[13]

Rosetti and Botticelli help us to see that Mary is our model. The God of hope favors each of us and, like Mary – like plain ol’ ordinary Mary – we have personal agency. We have the power to choose, and like Mary we can choose to get on with it, to be useful, to help others walk in the dark, to change the world!

The third painting I want to tell you about is contemporary artist John Collier’s Annunciation which hangs in the narthex of St. Gabriel Roman Catholic Church in McKinney, Texas. Collier portrays Mary as a young schoolgirl dressed in a blue and white parochial school uniform. She has dark hair pulled into a simple pony-tail. She is wearing white bobby socks and saddle oxfords, one of which is untied. As the angel Gabriel approaches her, she is on the porch of a modern suburban tract home as if coming home from school; she is reading a book.

Like Rosetti, Collier underscores Mary’s youth; like Botticelli, he portrays her timelessness by setting her in his contemporary frame. But this painting is brilliant because it also resurrects a medieval convention abandoned in the other two paintings. Countless paintings of the Annunciation from the Middle Ages show Mary studying a book, either the Psalms or the prophet Isaiah, as Gabriel interrupts her. Sometime during the Renaissance, many artists, like Botticelli and later Rosetti, stopped including the Virgin’s book. Collier has brought it back.

A visual pun based on the multiple meanings of the verb “to conceive,” a polysemy present in biblical Greek and ecclesiastical Latin as well as in English, the book points to Mary as a scholar, theologian, visionary, and contemplative. Conceiving Christ intellectually and spiritually through her study before conceiving him physically, Collier’s Mary and her medieval precursors enable and encourage all Christians to read and interpret scripture for ourselves and to conceive Christ in our hearts, minds, and spirits.

The 13th Century German mystic Meister Eckhart said:

We are all meant to be mothers of God. What good is it to me if this eternal birth of the divine Son takes place unceasingly, but does not take place within myself? And, what good is it to me if Mary is full of grace if I am not also full of grace? What good is it to me for the Creator to give birth to his Son if I do not also give birth to him in my time and my culture? This, then, is the fullness of time: When the Son of Man is begotten in us.[14]

Again, Mary is our model; through our study, contemplation, prayer, and action, we like her choose to conceive and bear the Word. Christ comes again, in and through us.

It’s not Christmas yet! It’s still the Fourth Sunday of Advent, so we focus our attention on Mary, an ordinary young woman who made an extraordinary choice and became an example of world-changing faith. She is standing right in front of us, speaking words of wisdom, words of freedom, words of personal agency and choice: “Let it be.” Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Fourth Sunday of Advent, December 24, 2023, to the people of Trinity Cathedral, Cleveland, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest preacher.

The lessons were from the Revised Common Lectionary, Year B, Advent 4: 2 Samuel 7:1-11,16; Romans 16:25-27; Psalm 89:1-4,19-26; and St. Luke 1:26-38. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

The illustration is Ecce Ancilla Domini by Dante Gabriel Rosetti, ca 1850-53, on display at the Tate Gallery, London.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Paul McCartney and John Lennon, Let It Be (1970)

[2] Sabine Baring-Gould, The Angel Gabriel’s Message, The Hymnal 1982, Hymn No. 265

[3] Luke Mosher, The Cestello Annunciation, Genius blog, undated, accessed 15 December 2023

[4] Andrew Hudgins, The Cestello Annunciation, in The Never-Ending: New Poems (Houghton-Mifflin, Boston:1991)

[5] Jeremy Richards, Mary’s Yes, sermon preached December 18, 2017, at Grant Park Church, Portland, OR, accessed 16 December 2023

[6] Malcolm Guite, A Sonnet for the Annunciation, Malcom Guite blog, March 24, 2012, accessed 21 December 2023

[7] Excerpt from a sermon of St. Anselm, ca. 955, Mary, Mother of the Re-Created World!, Crossroads Initiative, undated, accessed 16 December 2023

[8] Patrick Madrid, Ark of the New Covenant, Catholic Answers Magazine, December 1, 1991, accessed 21 December 2023

[9] Joe Laramie, S.J., Mary is a living tabernacle – and each time we receive the body of Christ, we are too, America, December 8, 2022, accessed 21 December 2023

[10] Madrid, op. cit.

[11] Eric Sentell, 8 Reasons Why “God Can’t” Is Better than “God Won’t” or “God Doesn’t”, Medium: Backyard Church, February 18, 2023, accessed 16 December 2023

[12] Archbishop Jeremy Greaves, installation sermon December 16, 2023, quoted in Michelle McDonald, Archbishop Jeremy Greaves Installed at St John’s Cathedral in a service blending ancient traditions and modern sensibilities, Anglican Focus, December 17, 2023, accessed 17 December 2023

[13] Evelyn Underhill, Incarnation and Childhood, in Light of Christ: Addresses Given at the House of Retreat, Pleshey, in May, 1932 (Wipf and Stock, Eugene, OR:2004), pages 41–42

[14] Meister Eckhart, Dum Medium Silentium (Sermon on Wisdom 18:14), in The Complete Mystical Works of Meister Eckhart, Maurice O’C. Walshe, tr. (Crossroad Publishing, New York:2009), page 29

Leave a Reply