When I was a kid growing up first in southern Nevada and then in southern California, the weeks leading up to Christmas (we weren’t church members so we didn’t call them “Advent”) were always the same. They followed a pattern set by my mother. We bought a tree and decorated it; we set up a model electric train around it. We bought and wrapped packages and put them under the tree, making tunnels for that toy train. We went to the Christmas light shows in nearby parks and drove through the neighborhoods that went all out for cooperative, or sometimes competitive, outdoor displays. My mother would make several batches of bourbon balls (those confections made of crushed vanilla wafers and booze) and give them to friends and co-workers. Christmas Eve we would watch one or more Christmas movies on TV, and early Christmas morning we would open our packages . . . carefully so that my mother could save the wrapping paper. Then all day would be spent cooking and watching TV and playing bridge. After the big Christmas dinner, my step-father and I would do the clean up, my brother and my uncle would watch TV . . . and my mother would sneak off to her room and cry. You see . . . no matter how carefully we prepared, no matter how strictly we adhered to Mom’s pattern, something always went wrong. We never got it right; Christmas never turned out the way my mother wanted it to be.

When I was a kid growing up first in southern Nevada and then in southern California, the weeks leading up to Christmas (we weren’t church members so we didn’t call them “Advent”) were always the same. They followed a pattern set by my mother. We bought a tree and decorated it; we set up a model electric train around it. We bought and wrapped packages and put them under the tree, making tunnels for that toy train. We went to the Christmas light shows in nearby parks and drove through the neighborhoods that went all out for cooperative, or sometimes competitive, outdoor displays. My mother would make several batches of bourbon balls (those confections made of crushed vanilla wafers and booze) and give them to friends and co-workers. Christmas Eve we would watch one or more Christmas movies on TV, and early Christmas morning we would open our packages . . . carefully so that my mother could save the wrapping paper. Then all day would be spent cooking and watching TV and playing bridge. After the big Christmas dinner, my step-father and I would do the clean up, my brother and my uncle would watch TV . . . and my mother would sneak off to her room and cry. You see . . . no matter how carefully we prepared, no matter how strictly we adhered to Mom’s pattern, something always went wrong. We never got it right; Christmas never turned out the way my mother wanted it to be.

Some years later, I read the work of the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai and I understood what our family problem was.

Amichai wrote:

From the place where we are right

Flowers will never grow

In the spring.The place where we are right

Is hard and trampled

Like a yard.But doubts and loves

Dig up the world

Like a mole, a plow.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

Where the ruined

House once stood.[1]

Mom had tried so hard to be right –– and we had all tried so hard right along with her –– so hard to get Christmas right that it was trampled into that hard ground and never blossomed.

When I grew up and joined to the Church, I found that it like my family also had a pattern for the weeks leading up to Christmas and I learned to call that pattern “Advent.” The pattern is laid out in the three-year Eucharistic Lectionary.

The gospel lessons for Advent follow the same order every year regardless of which year of the Lectionary cycle we may be in. On the first Sunday, we get something from Jesus’ apocalyptic prediction of his return.[2] On Advent Two and Three, the focus is first John the Baptizer as the fulfillment of the prophecy of a forerunner, a “voice crying in the wilderness,”[3] and then (where we are today) his specific role as herald for Jesus.[4] We finish up Advent with some pre-birth story of who Jesus will be; next week we’ll hear the story of Joseph’s re-assuring dream.[5] Every year, the same pattern.

We accompany these gospel stories with readings from the prophets, in Years A and B mostly from Isaiah so that we hear nearly all of the texts of Handel’s Messiah, and in Year C selected readings of Jeremiah, Malachi, Zephaniah, and Micah.[6] (Apparently the lectionary editors used up all the appropriate Isaiah passages in the first two years.) Interestingly, in the first two years, the emphasis seems to be on building roads, repairing highways, rebuilding cities, and planning temples, and in the third year, after all of Isaiah’s construction work, the other prophets tell us to get cleaned up and put on our party clothes. Again, there’s a pattern to Advent.

Underlying the Advent pattern is the message of the epistles. Every year, the message from the letters is the same: be patient, be strong, be steadfast in prayer.[7] Whether it’s from Paul, or James, or Peter, or one of the letters of unsure authorship, the message is nearly always something like the first verse of today’s epistle: “Be patient, therefore, beloved, until the coming of the Lord.”[8]

Frequently, the Advent epistles encourage us to moderation: to be at peace with our neighbors, to “be blameless,”[9] to “strive to be found . . . without spot or blemish,”[10] so that (in the words of today’s epistle) we “may not be judged.”[11] In a word, the epistles in the Advent lectionary (like my mother) encourage us to get it right, and that is where I think the Advent lectionary (like my childhood family) gets it wrong.

Advent is not about being right; it is about being ready, and sometimes that means being radical, maybe even rebellious, and quite possibly ridiculous. We are supposed to follow a different pattern!

You see . . . there was a man who bought himself some new underwear. He wore that underwear for several weeks without bathing and without doing his laundry; then he took the underwear and buried it under some rocks and left it there for several more weeks. Eventually, he dug up the underwear and then went about the city telling people, “This underwear is your relationship with God!”[12]

There was another man who built a little replica of his city in the town square, then lay down next to it on his left side and pretended to attack it … for over a year! Then he got up, lay down on his right side and heaped curses on that toy city for another forty days. This, he told anyone who would listen, was how God was going to deal with the people of the city.[13]

A third man wandered around his city naked and barefoot for three years proclaiming that this would be the fate of anyone who opposed God.[14] A fourth man married a prostitute knowing that she was a prostitute and that she would continue to be a prostitute and that she would be unfaithful to him, and when she did he said to his neighbors, “You are just like my wife! You are just like my wife and the way she behaves toward me is the way you behave toward God!”[15]

The first man, the underwear guy, that was Jeremiah; the fellow with the toy city was Ezekiel; the barefoot-and-naked man was the first Isaiah; and the prostitute’s husband was Hosea. When James admonishes us to appropriate Advent behavior in today’s epistle, it is to these guys that he points as models: “As an example of suffering and patience, beloved, take the prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord.”[16] The prophets did not merely speak in God’s Name, they acted out in God’s Name in these theatrical, disruptive, and rebellious ways.

These are what are called “sign acts” –– “nonverbal actions and objects intentionally employed by the prophets so that message content was communicated through them to the audiences.”[17] There are at least thirty-three such “street theatre” acts recorded in the bible.[18] This prophetic behavior is the model that James commends to us as the pattern for Advent.

I’m fairly certain that none of these men were thought of by their contemporaries as paragons of moderation, harmony, blamelessness, or steadfast calm. Their neighbors probably thought they were fools, if not outright lunatics. They were radicals and revolutionaries, and John the Baptizer was very much like them. Matthew described his prophetic theatricality in last week’s gospel lesson. John “wore clothing of camel’s hair with a leather belt around his waist;” he ate a diet of “locusts and wild honey;” and he addressed religious leadership as a “brood of vipers.”[19]

John’s whole schtick of baptizing people in the River Jordan as a symbol of repentance from sin was a prophetic sign act in the performance of which he dramatically criticized the religious authorities and the politically powerful, particularly King Herod and his adulterous wife.[20] That was a rebellious and ridiculous, and dangerously foolhardy, thing to do. It’s no wonder we find him in prison in today’s gospel lesson, sitting in his cell wondering about Jesus.

“Did I get it right?” John wanted to know, so he sent his disciples to Jesus to ask, “Are you the one?”[21]

Jesus’ reply demonstrates that he, too, was in the mold of the ancient prophets. He doesn’t simply tell John’s emissaries what he’s been saying, nor does he say, “Yep. You got it right.” He shows them what he’s done. “Go and tell John what you hear and see,” he says, “[Tell him about the prophetic sign acts:] the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them. And blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me.”[22] In other words, Isaiah’s revolutionary vision which we read this morning ––

. . . the eyes of the blind shall be opened,

and the ears of the deaf unstopped;

. . . the lame shall leap like a deer,

and the tongue of the speechless sing for joy[23]

–– was being realized.

When John’s disciples had left, Jesus turned to the crowd and praised John, not because he was a model of moderation who got it right, nor because he was a peaceful and blameless paragon of steadfast calm (that would be the folks “who wear soft robes [and] are in royal palaces”[24]). John was none of those things; he was a prophet, like Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Hosea, those wild and rebellious, radical, and even foolhardy men James commends to us as our models of Advent “suffering and patience.”[25] Jesus praised John because John was a prophet sent to “prepare the way of the Lord.”[26] John had asked the wrong question: John wasn’t tasked with getting things right; he was tasked only with getting things ready.

The prophet Isaiah, in all his barefoot-and-naked craziness, made a promise on behalf of God: he proclaimed a “peaceable kingdom” in which “the leopard shall lie down with the kid . . . the cow and the bear shall graze [together]” and children will safely play with snakes and serpents.[27] “The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad,” he said. “The desert shall rejoice and blossom . . . waters shall break forth in the wilderness, and streams in the desert; the burning sand shall become a pool, and the thirsty ground springs of water.”[28] Throughout the ages, humankind has acted as if it’s our responsibility to make all that happen, that if we can just get it right, the peaceable kingdom will come. And that’s where we get it wrong, because (as the poet said) “from the place where we are right, flowers will never grow.”[29]

“Did I get it right?” asked John.

“You got it ready,” answered Jesus.

That is our pattern for Advent.

Amen.

====================

This homily will be offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the 3rd Sunday of Advent, December 15, 2019, to the people of St. James Episcopal Church, Wooster, Ohio, where Fr. Funston will “supply” as guest clergy.

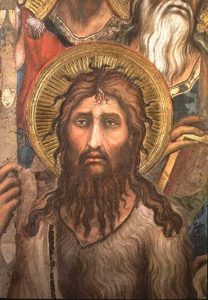

The illustration to this page is a detail of John the Baptizer from the Maestà (Madonna with Angels and Saints) by Simone Martini, 1312 – 1315, fresco, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. See Art in Tuscany, website accessed 12 December 2019.

The lessons scheduled for the service (Advent 3, Year A) Isaiah 35:1-10; Psalm 146:4-9; James 5:7-10; and St. Matthew 11:2-11. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai, Chana Bloch & Stephen Mitchell, trs., (UC Press, Berkeley: 1996), p. 34.

[2] Year A: Matthew 24:36-44; Year B: Mark 13:24-37; Year C: Luke 21:25-36

[3] Year A: Matthew 3:1-12; Year B: Mark 1:1-8; Year C: Luke 3:1-6

[4] Year A: Matthew 11:2-11; Year B: John 1:6-8, 19-28; Year C: Luke 3:7-18

[5] Year A: Matthew 1:18-25; Year B: Luke 1:26-38; Year C: Luke 1:39-45, (46-55)

[6] Year A: Isaiah 2:1-5; Isaiah 11:1-10; Isaiah 35:1-10; and Isaiah 7:10-16. Year B: Isaiah 64:1-9; Isaiah 40:1-11; Isaiah 61:1-4, 8-11; and 2 Samuel 7:1-11, 16. Year C: Jeremiah 33:14-16; Baruch 5:1-9 or Malachi 3:1-4; Zephaniah 3:14-20; and Micah 5:2-5a.

[7] Year A: Romans 13:11-14; Romans 15:4-13; James 5:7-10; and Romans 1:1-7 Year B: 1 Corinthians 1:3-9; 2 Peter 3:8-15a; 1 Thessalonians 5:16-24; and Romans 16:25-27. Year C: 1 Thessalonians 3:9-13; Philippians 1:3-11; Philippians 4:4-7; and Hebrews 10:5-10

[8] James 5:7

[9] 1 Corinthians 1:8; Philippians 1:10

[10] 2 Peter 3:14

[11] James 5:9

[12] Jeremiah 13:1-11

[13] Ezekiel 4:1-8

[14] Isaiah 20:1-6

[15] The Book of Hosea

[16] James 5:10

[17] K. G. Friebel, Sign Acts, Dictionary of the Old Testament: Prophets, Mark J. Boda & J. Gordon McConville, eds., (Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL: 2012), pg 707; see also Whitney Woollard, Sign Acts: The Weird, Wonderful World of Prophetic Communication, The Bible Project, website accessed 12 December 2019.

[18] See Steve Rudd, 33 Theatrical Prophetic Sign Acts in the Bible, The Interactive Bible, website accessed 12 December 2019

[19] Matthew 3:4,7

[20] Mark 6:17-19

[21] Matthew 11:3

[22] Matthew 11:4-6

[23] Isaiah 35:5-6

[24] Matthew 11:8

[25] James 5:10

[26] Isaiah 40:3; cf. Malachi 3:1 and Matthew 11:10

[27] Isaiah 11:6-7

[28] Isaiah 35:1,6-7

[29] Amichai, op. cit.

Leave a Reply