====================

This sermon was preached on Sunday, June 24, 2012, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector. (Revised Common Lectionary for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost, Proper 7: Job 38:1-11; Psalm 107:1-3, 23-32; 2 Corinthians 6:1-13; and Mark 4:35-41.)

====================

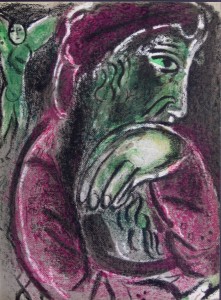

Our first reading this morning is from the Book of Job, which in the Jewish organization of Scripture is part of the Ketuvim or “Writings” and is considered one of the Sifrei Emet or “Books of Truth”, which is really quite interesting since it is generally acknowledged to be a work of fiction. It tells the story of Iyyobh (“Job”), who is described as a righteous man and who becomes the subject of a wager between a character called “Satan” and another character called “God”. I put it that way to underscore that this text is not relating to us any historical facts about God, or Satan, or a man named Job; it is, rather, telling a story in which characters representing God, Satan, and human beings in general help us to understand something about reality.

Our first reading this morning is from the Book of Job, which in the Jewish organization of Scripture is part of the Ketuvim or “Writings” and is considered one of the Sifrei Emet or “Books of Truth”, which is really quite interesting since it is generally acknowledged to be a work of fiction. It tells the story of Iyyobh (“Job”), who is described as a righteous man and who becomes the subject of a wager between a character called “Satan” and another character called “God”. I put it that way to underscore that this text is not relating to us any historical facts about God, or Satan, or a man named Job; it is, rather, telling a story in which characters representing God, Satan, and human beings in general help us to understand something about reality.

So here’s the story. God and Satan make a wager that Satan can do nothing to the righteous man, Job, that will sway his faith in God. Satan then arranges to deprive Job of everything that seems to give value and meaning to his life – his family, his wealth, his social position, his health – so that he is left with nothing. Instead of cursing God (even though encouraged to do so by his wife), Job shaves his head, tears his clothes, and says, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return there; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” (Job 1:21)

Job is then visited by three of his friends who try to comfort him based on their individual ways of understanding religion and God. Each of these men bases his appeal on a particular religious premise:

First, Eliphaz comes with a faith that says the innocent never suffer permanently. He believes that Job is essentially innocent, but even the most innocent of humans must expect some suffering, even if only temporary. Therefore, he assures Job that things will get better soon.

Second is Bildad who is convinced of the doctrine of retribution. Given the demise of Job’s family, they must have been very wicked, but since Job is still alive and there must be some hope for him. He just needs to repent of whatever evil he must surely have done.

The third friend, Zophar, believes that Job is guilty of some dread sin because he is suffering and even worse, Job refuses to acknowledge it, therefore he is a far worse sinner than anyone could have imagined. Zophar offers no hope whatsoever.

Then a fourth character, Elihu, comes along. Elihu is angered by everything the first three men say, as well as by Job’s protestations of innocence; he seeks to persuade Job to focus on God and to realize that no one is ever able to understand God. True wisdom, he says, is found in the reverence of God.

But in nothing that any of these four men say does Job find much comfort; in nothing they say does he find an answer to what is his basic question: Why does a righteous person suffer? And why do the wicked seem to escape punishment?

Throughout the speeches of his friends, Job protests his innocence and demands, again and again, the right to present his case to God, to go to court with God and get an answer to his question: “Why is this happening to me?” When that appears to impossible, Job’s response is what one commentator has called “a powerful, evocative, authentic expression of man’s essential egotism.” Having seen and felt too much suffering, all Job wants is to see nothing at all; if he cannot present his case to God, he wants only to be enveloped in the blackness of the tomb, to be enclosed by dark doors that will remain shut forever.

And this, finally, is when God shows up. Not with an answer to Job’s self-centered, legal question, but in response to his withdrawal inward and turning out of the lights. “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?” God demands of Job, “Gird up your loins like a man, [and] I will question you.” (Job 38:2-3) Stop being a self-centered little worm; stop wallowing in self-pity; stop whining “Why me?” Look at the bigger picture!

This is not the answer Job expected; it is not the hearing in a court that Job had envisioned, where God would hear him and vindicate his cause. This is not the solution to his wanting to know why bad things happen to good people. God takes the focus away from the “up close and personal” issues of Job’s life and suffering, and instead presents the bigger picture of the whole of creation where God’s unfathomable being undergirds everything.

Job wants answers about justice but God goes into a rant about the creation: the sea, the stars, the sky, the earth, the whole shebang! As the speech goes on for several chapters, God will talk about all the wild animals, even the ostrich, who is incredibly foolishness but very very speedy. What are we to make of this? Job wants fairness; he wants what’s right! And God’s answer is, “Hey! Look at that ostrich I made! It’s stupid but, wow, is it fast!” What’s the point?

Job wants answers about justice but God goes into a rant about the creation: the sea, the stars, the sky, the earth, the whole shebang! As the speech goes on for several chapters, God will talk about all the wild animals, even the ostrich, who is incredibly foolishness but very very speedy. What are we to make of this? Job wants fairness; he wants what’s right! And God’s answer is, “Hey! Look at that ostrich I made! It’s stupid but, wow, is it fast!” What’s the point?

Well, the point is this – that Job is not the center of the universe . . . and neither are we. That’s why the Jews call this poetic work of fiction a “Book of Truth”. What Job learns, we learn – that we are not center stage in the drama of creation. The world is not ours; it’s God’s.

In the place of Job’s egotistical death wish, God offers the splendor and vastness of life. In place of an inward focus toward darkness, God offers a grand sweeping view that carries us over the length and breadth of the created world, from sea to sky to the whole created cosmos, to the lonely wastes and craggy heights where only the grass or the wildest of animals live, where the ostrich runs swiftly, where God ” bring[s] rain on a land where no one lives, on the desert, which is empty of human life.” (Job 38:26)

Job and his friends were completely wrong about God. God is simply not in the business of rewarding and punishing individual human beings. God’s revelation to Job and to us is that the universe is far bigger, far stranger, and far more mysterious than we can imagine, and that God’s providential care is at the heart of all creation. The comfort for Job and for us is found in being reminded that we are one of God’s creatures in this web of creation.

Obviously, this is not the comfort Job had hoped for, but it is the comfort God offers. And it is the comfort Jesus demonstrates in today’s Gospel lesson. Asleep in the stern of a boat tossed in a wild and stormy sea, Jesus seems unconcerned about the comfort of the disciples who are with him. They wake him and, echoing the God of the story of Job saying to the sea, “Thus far shall you come, and no farther; here shall your proud waves be stopped,” he commands the waves, “Peace! Be still!” And turning to the disciples he asks, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” We can almost hear him say, “Haven’t you read the Book of Job?”

Back in 1735, the Anglican priest and founder of Methodism John Wesley sailed from England to Savannah, Georgia, with his brother Charles, also an Anglican priest. Their goal was to preach to the Indians and lead them to Christ. On the crossing, which took four months, there was also a group of Moravians. At one point, a storm came up suddenly and broke the main mast. John Wesley reported in his journal that while the Englishmen on board were terrified, the Moravians calmly sang hymns and prayed. Wesley was impressed by their faith in the face of a dangerous, life-threatening storm. He felt that they possessed an inner strength that he did not. He later wrote in his journal, “It was then that I realized that mine was a dry-land, fair-weather faith.”

The Book of Job and today’s gospel lesson encourage us to have more than a “dry-land, fair-weather faith.” They commend a faith in the God of creation who “know[s] the ordinances of the heavens . . . [and] establish[es] their rule on the earth.” (Job 38:33) The Book of Job encourages us to look beyond our own self-centered concerns, to see the broad panorama of God’s power, to find comfort in God’s creating and sustaining the splendor and vastness of life.

Little wonder that the Jews call this work of fiction, the Book of Job, a “book of truth!”

Let us pray:

Heavenly Father, you have created the world and filled it with beauty: Open our eyes to behold your gracious hand in all your works; that, rejoicing in the whole of your creation, we may learn to serve you with gladness; for the sake of the One through whom all things were made, the One whom even the wind and the sea obey, your Son Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Leave a Reply