Once again we are in the 22nd Chapter of Matthew which we began last week with Jesus telling that strange parable of the wedding banquet, but to truly understand what is going on here we have to go back to Chapter 21.

At the beginning of Chapter 21, Jesus tells two disciples to go to Bethphage and untie the foal of a donkey which he needs to ride into the city of Jerusalem. When I tell you that, you should immediately realize that this story takes place on or shortly after Palm Sunday; in fact, today’s confrontation takes place on the Monday after Palm Sunday. Jesus rode into the city in triumph and was haled as a king, as the One who comes in the Name of the Lord. He had gone to the Temple and driven out the sellers of sacrificial animals and the money-changers. After that, he returned to Bethany and spent the night, probably in the home of his friends Mary and Martha. The next day he went back to the Temple and began teaching in parables, during which he is confronted by various power groups – the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Herodians, and probably others.

At the beginning of Chapter 21, Jesus tells two disciples to go to Bethphage and untie the foal of a donkey which he needs to ride into the city of Jerusalem. When I tell you that, you should immediately realize that this story takes place on or shortly after Palm Sunday; in fact, today’s confrontation takes place on the Monday after Palm Sunday. Jesus rode into the city in triumph and was haled as a king, as the One who comes in the Name of the Lord. He had gone to the Temple and driven out the sellers of sacrificial animals and the money-changers. After that, he returned to Bethany and spent the night, probably in the home of his friends Mary and Martha. The next day he went back to the Temple and began teaching in parables, during which he is confronted by various power groups – the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Herodians, and probably others.

In this conversation, Matthew tells us that Jesus’ antagonists are the Pharisees and the Herodians. That’s important information because any sort of cooperative action between those two groups was darn near impossible. Matthew is saying something here like, “Harry Reid and John Boehner went together to ask Jesus this question.” It’s like saying that a Tea Partier and a participant in Occupy Wall Street took a united stand on something.

Pharisees, of course, were the Jewish sticklers for the Law. They insisted that righteousness required adherence to every little “jot and tittle” of the Mosaic rules. Herodians on the other hand weren’t Jews at all! They were Idumeans who had come to rule in Jerusalem with their king, Herod, as puppets under the Romans; they didn’t give one wit for the Law. But here they are confronting Jesus together because both felt threatened by him.

They come and ask what sounds like a simple question: Under the Jewish Law is it permissible, for a Jew, to pay taxes to the Romans? They’re trying to trap Jesus – if he says “Yes” he’ll lose the support of religious Jews and his movement will fizzle; if he says “No” he’ll be liable to arrest and prosecution by the Romans as political troublemaker and his movement will lose its leader and fizzle. They win in either case.

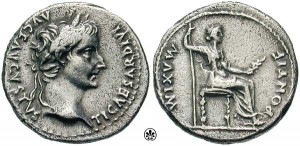

Jesus, however, is not going to fall for the trap. He asks to see one of the coins that would be used to pay the tax. Doing so, he traps them and points out how ridiculous their alliance is. The Pharisees, under the Law, could not possibly have possessed the coin in question and would never have brought one into the Temple precincts. Under the Jewish Law it was absolutely forbidden to bring into the Temple anything bearing an image, especially something bearing a religious image, an idol of a foreign religion. On one side, the coin in question, a denarius, would have had an image of Caesar and the words, Augustus Tiberius Caesar Divi Augusti Filius – “Augustus Tiberius, Emperor, son of the Divine Augustus”; on the other side, Caesar’s title Pontifex Maximus– “High Priest”. In other words, the coin was a religious object; it proclaimed the creed of the emperor-worship cult which was part of the Roman civic religion. The Herodians, client rulers of the Romans, would have had no problem with the coin, but it would have been anathema to the Pharisees. By asking for the coin, and getting a Herodian to produce one, Jesus was demonstrating to everyone who utterly ridiculous this alliance between the two parties was.

Jesus’ answer to the question, though, is what truly exposes the hypocrisy of their partnership: “Give [back] therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matt. 22:21). (Our New Revised Standard Version of the text says to “give” to the emperor – the word “render” is more familiar to many of us from the King James Version – but the Greek verb is apodidomi, which means to “give back”, to “return” or to “repay”.)

Jesus’ answer is tricky; it gets to the very heart of the matter and points out how very different these two parties are. The Herodians would be perfectly happy with Jesus’ reply; they would be satisfied with an answer that seems to suggest that we owe equal allegiance to the governing authorities and to God, that the political realm and the religious realm place separate but equal demands upon us and that we are obliged to obey both. There are plenty of modern American folks who would agree with them, too.

To the Pharisees, on the other hand, “The earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it, the world and all who dwell therein.” (Ps. 24:1 They would that morning have said in their daily prayers, “It is our duty to praise the Master of all, to ascribe greatness to the Molder of primeval creation” (the Aleinu); thus, they would have prayed that God’s Name be “exalted and sanctified in the world that he created” (the Kaddish). If, as these prayers suggest, all things belong to God, then what can possibly be left over to return to the emperor? Both the Pharisee and the Herodians are left wondering what Jesus really means. Whose side (if any) he is really on?

Of course, the answer to that question is that Jesus is on neither side of that division. Jesus is on God’s side.

But we, like the Pharisees and the Herodians, are left here wondering, what does this answer mean for us? How are we to understand and live out Jesus’ answer?

By answering, “Repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar,” Jesus is not unambiguously saying, “Go ahead, pay your taxes!” Rather, by placing the emperor and God in parallel, Jesus also makes parallel their images. They give him the denarius and he gives it right back to them with this question, “Whose head is this, and whose title?” And, of course, they answer, “Caesar’s.” “OK, fine,” says Jesus, “it must be his. Give it back to him.” The second half of the answer, “and [give] to God what belongs to God,” is comprehensive and includes all areas of life. Having pointed out whose likeness is on the coin, Jesus answer demands that we then ask ourselves and answer the further question, “What – or (better) who – bears God’s image?”

After this confrontation, the 22nd Chapter of Matthew contains two more challenges to Jesus. The Sadducees, after the Pharisees and the Herodians walk away, present their rather silly hypthetical about the imaginary woman who married seven brothers in succession and ask, “Whose wife will she be in the afterlife?” (in which the Sadducees, by the way, don’t even believe). Then the kicker … a lawyer asks him, “Teacher, which commandment is the greatest?” Jesus, as we will hear in next week’s Gospel lesson, is that loving God with one’s whole heart, mind and soul is the first and greatest commandment, and the second, loving one’s neighbor as oneself, is just as important. Humans, not coins, bear God’s true image, and no edict of Caesar, no tax imposed or law declared by the secular government, can absolve Jesus’ followers from the mandate to love God and to see and serve God in our neighbor.

To what seemed like a trick question Jesus responded, “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.” On that ancient denarius that was given to Jesus was an image of Caesar, merely money was owed to him, whereas every human being bears the image of God, implying that each of us, and all of us together, “render to God,” the Master of all and the Molder of creation, our selves, our entire selves wholly and without reservation.

Let us pray:

Almighty and eternal God, so draw our hearts to you, so guide our minds, so fill our imaginations, so control our wills, that we may be wholly yours, utterly dedicated to you; and then use us, we pray, according to your will, and always to your glory and the welfare of your people; through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

Leave a Reply