====================

This sermon was preached on the Sixth Sunday after Epiphany, February 16, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Deuteronomy 30:15-20; Ecclesiasticus 15:15-20 (used as the gradual); 1 Corinthians 3:1-9; and Matthew 5:21-37. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

As I have mentioned here more than a couple of times, I went to high school at a boarding school in the middle of nowhere . . . a place called Kansas. At the time, my family was living in Southern California in the San Fernando Valley area of Los Angeles, so I was very far from home. Truth be told, nearly all of us in the cadet corps of St. John’s Military School in Salina were far from home; there were very few Kansans in the student body.

As I have mentioned here more than a couple of times, I went to high school at a boarding school in the middle of nowhere . . . a place called Kansas. At the time, my family was living in Southern California in the San Fernando Valley area of Los Angeles, so I was very far from home. Truth be told, nearly all of us in the cadet corps of St. John’s Military School in Salina were far from home; there were very few Kansans in the student body.

The dormitory at the school was called “the barracks” but, in truth, it wasn’t barracks-style living with everyone sharing one big room. We had discrete two-, three-, or four-bed rooms; there were also single rooms, but those were reserved to the highest ranking officers of the cadet battalion. At the end of each year, you could request a particular room for the next school year. Each size of room had its particular advantages; the four-bed rooms were newer, had better study carrels, nicer beds, and larger closets. So at the end of my first year, I requested a four-person room for the coming year.

You could also request particular roommates but that didn’t always work out. It usually would if it was just two people agreeing to share a two-bed room, but even then you couldn’t be guaranteed a roommate. I really didn’t care, so I just asked for the size of room I wanted and trusted to the luck of the draw for my roommates.

We got notice in late July what our room assignments were and who are roommates would be. As it turned out, two other continuing students with whom I was good friends got assigned to the same room, as did a new kid. I think they may have assigned him to room with me because, like me, he was from Southern California — San Diego, to be exact.

So I get this notice and it tells me that my roommates will be the two guys I knew and someone named “Joseph Joachim __________.” Well, with a name like that I was pretty certain that he was going to turn out to be Roman Catholic and Latino, specifically, since he was from San Diego, I figured he’d be a Mexican-American. So in August, when I reported to school, I was expecting to meet someone with brown skin and dark hair, and probably smaller than me. (This is an object lesson in never forming expectations based solely on someone’s name!)

What I encountered, instead, was a young man who stood about 6′ 2″ and towered over me! Plus, he had flaming red hair and a face full of freckles. He looked as Irish as Brian Boru! And turned out to be Jewish.

We became good friends and through that friendship, I had my first introduction to Judaism. Jojo (that was his nickname, Joseph Joachim shortened to “Jojo”) took me with him to a Chanukah party at one of the local — actually, I think, the only synagogue in Salina, Kansas, and it was there, also, that I experienced a Passover Seder for the first time. It was also because of my friendship with Jojo that I first experienced a traditional Jewish wedding.

I was attending college in San Diego, Jojo’s hometown. Jojo, though a year behind me in high school, had graduated from college before me, and shortly after completing his degree decided to get married. He invited me to be a part of that celebration and I accepted. One of the traditions of a Jewish wedding (as in every wedding) is the offering of toasts and one frequently given is the Hebrew salutation, “L’chaim!” — “To Life!” It is a wish for a person’s, or in this case the couple’s, health and well-being.

Jojo’s father was the first to offer the toast. I was standing beside him as he did so, and I may have been the only person to hear a muttered after-thought that he spoke when giving the toast. He said the usual few words about how proud and happy he was, loudly proclaimed “L’chaim!” and then muttered, “And don’t screw it up.”

That is precisely what Moses is saying to the people of the Hebrews today in our reading from the Old Testament: “L’Chaim! – And don’t screw it up!”

Remember where we are in this reading. The Book of Deuteronomy is supposed to be the farewell address from Moses to the people he has led across the desert for forty years. The first generation that had left Egypt has died off — you may remember that they angered God with their stiff-necked whining so God had sworn that none of them could enter the Promised Land, even Moses! God has promised Moses, however, that he would be able to see Canaan, even though he couldn’t go in.

So in Deuteronomy, we are standing on a high hill looking over the border into Canaan-land and Moses is reminding the Hebrews of their past. In a series of three discourses, Moses reminds them of their time of slavery in Egypt, of their liberation at the Passover, of their trek through the desert, and of God’s giving of the Law at Sinai. He has recounted the Ten Commandments and the rest of 613 mitzvot required in the Torah. And he is now, in the third discourse, consigning the Hebrews to the leadership of his assistant, Joshua the son of Nun, and encouraging them to success in the land God is giving them.

In the portion that was read this morning he says to them, “I am laying before you a choice between life and death. Choose life.” And then he tells them that doing so successfully is really a very simple thing; there are only three elements, three things that have to be done. There may be ten major commandments and 613 little rules and regulations, but really there are only three things that are required for them to live a good life in the land God is giving them: love God, obey God, and be faithful. He underscores this by saying it twice in this short passage: “If you obey the commandments of the Lord your God that I am commanding you today, by loving the Lord your God, walking in his ways, and observing his commandments, decrees, and ordinances, then you shall live . . . .” (v. 16) and again “Choose life so that you and your descendants may live, loving the Lord your God, obeying him, and holding fast to him . . . .” (vv. 19b-20) Love God, obey God, and be faithful. Choose life!

Or as Jojo’s father put it, “L’Chaim! And don’t screw it up!”

In our epistle lesson, Paul is writing to the Christians in Corinth. He’s gotten word that they are screwing it up! The church he planted there has become split; there is conflict; people are following different practices and different teachings, dividing themselves according to whomever they were converted or baptized or taught by. “It has been reported to me by Chloe’s people,” he says in the beginning of this letter, “that there are quarrels among you.” (1 Cor. 1:11) The followers of Apollos were at odds with followers of Paul and both were at odds with the followers of Cephas.

In correcting them, Paul basically tells them that they are acting like children! He reminds them that in proclaiming the Gospel to them he spoke to them as if they were children: “I could not speak to you as spiritual people, but rather as people of the flesh, as infants in Christ. I fed you with milk, not solid food, for you were not ready for solid food. Even now you are still not ready . . . . (1 Cor. 3:1-2)

Paul made the same point about religion, really about maturity in religion, in his letter to the Galatians when he spoke of the Jewish law (the Torah, the same law of ten major commandments and 613 mitzvot about which Moses had spoken to the Hebrews on that hill overlooking Canaan) as a “disciplinarian”:

Before faith came, we were imprisoned and guarded under the law until faith would be revealed. Therefore the law was our disciplinarian until Christ came, so that we might be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer subject to a disciplinarian, for in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith. (Gal. 3:23-26)

The actual Greek word is paidagogos which is more accurately translated as “tutor” or “schoolmaster.” It is the word from which we get pedagogy.

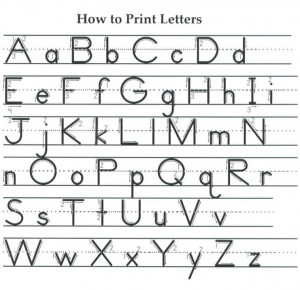

As I thought about this image of learning, this metaphor of the Law as schoolmaster, I thought about the way we all learn to write, by first learning to letter (or “print” as some people call it). I’m sure we all started in the same way, with those workbooks with very wide ruled lines, maybe 1/2 inch? And there were dashed lines over which we traced with our pencils. We started with the straight-line letters . . . I . . . then added a crossbar at the top . . . T . . . or a bar at the bottom . . . L . . . then two bars . . . F . . . and so on. Eventually, when we had mastered the straight lines, we learned to make diagonals . . . X . . . and . . . Z . . . and then . . . Y And after that came the curved letters . . . O . . . then . . . C . . . then . . . S. And I remember that . . . Q . . . was last because it had that little squiggly addition.

As I thought about this image of learning, this metaphor of the Law as schoolmaster, I thought about the way we all learn to write, by first learning to letter (or “print” as some people call it). I’m sure we all started in the same way, with those workbooks with very wide ruled lines, maybe 1/2 inch? And there were dashed lines over which we traced with our pencils. We started with the straight-line letters . . . I . . . then added a crossbar at the top . . . T . . . or a bar at the bottom . . . L . . . then two bars . . . F . . . and so on. Eventually, when we had mastered the straight lines, we learned to make diagonals . . . X . . . and . . . Z . . . and then . . . Y And after that came the curved letters . . . O . . . then . . . C . . . then . . . S. And I remember that . . . Q . . . was last because it had that little squiggly addition.

What was the point of that? Were we learning to trace dashed lines? Not really. The rule was to trace the dashed line, but what we were learning was lettering, writing, and really not even that . . . what we were learning was a means of communication! The point was not to trace dashed lines; the point was to communicate.

As I thought about that further, I remembered my grandfather Funston. I’ve mentioned him a time or two and told you how I spent my childhood summers with my grandparents. My grandfather, when I knew him, was an insurance salesman, the owner of the Funston Insurance Agency on Fourth Street in Winfield, Kansas (another part of the middle of nowhere). But earlier in life, before he “retired,” he was a school teacher, and he had been a certified Palmer method penmanship instructor. So one of the “fun” things his grandchildren got to do during their summer vacations was learn to write in cursive. Does anybody do that anymore? Write what we used to call “long-hand”? Email begat texting and texting begat tweeting and it seems no one writes notes or letters in beautiful flowing script anymore. But my grandfather made sure that my cousins and I learned to write that way!

There was one sentence that we practiced over and over. Later, in high school at St. John’s Military School, when I learned to type from a retired baseball player named “Lefty” Loy, I encountered that sentence again. And when my mother and I bought my first typewriter for college, we used that sentence to test the key action — and still to this day when I test computer keyboards I type out that same sentence. It’s one that I am sure is familiar to many if not most of you: “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy white dog.” An English sentence containing every letter of the Latin alphabet.

Writing that sentence again and again, typing it over and over, was I learning about brown foxes or white dogs? No! The rule was to write or type the sentence, but the goal was to learn yet another means of written communication. The dashed lines in the workbook, the constant repetition of that sentence were training us in an underlying principle. In Paul’s words, they served as a schoolmaster until we had internalized the lessons. The Law of Moses, the Ten Commandments, the 613 mitzvot, served as schoolmaster until the Hebrews had (as Moses said) learned to love God, obey God, and be faithful. Until they had learned to choose life.

But over time, the rules and regulations, the commandments, the laws, and the ordinances had become more important than those underlying principles. They screwed it up! So that the tracing of the dashed lines was more important than the communication. Then, through God’s grace, Jesus came “so that we might be justified by faith,” so that we might be set free from a disciplinarian, from a schoolmaster which had become more important the lessons the schoolmaster was supposed to teach.

In our Gospel lesson, Jesus is on a hillside beside the Sea of Galilee delivering what we have come to know as “The Sermon on the Mount.” And here in this section we hear a part of what are known as “the antitheses” in which Jesus deals with this very issue. He takes apart the Torah and shows that beneath its specific rules is an underlying principle by dealing with several of the commandments in this fashion: “You have heard it said . . . . but I say to you.” You have heard the rule, but I tell you something more basic, something that is the foundation of the rule.

For example, he begins with the commandment, “You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, `You shall not murder’; and `whoever murders shall be liable to judgment.'” (v. 21) So, why do people commit murder? The last time you murdered someone, why did you do it? Statistically, we know that most murders are committed in what the law calls “the heat of passion.” In other words, people mostly kill other people because they’re angry! They’re mad as hell and lose control. So Jesus says, “But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment.” And he continues to say that if you act on that anger in any way you will be liable to damnation. It isn’t the rule against murder that is, in and of itself, important; it is the underlying principle of not losing control to anger. The commandment is a schoolmaster; the commandment is a dashed line; the commandment is a repetitive sentence teaching us the foundational lesson to control our passions. And so Jesus continues with the commandment against adultery and its relationship to foundational issue of lust and covetousness, and with the commandment against false swearing and its relationship to the foundational issue of honesty. And so it goes for all of the Ten Commandments and all of the 613 mitzvot. And the foundational principle for the whole of the Torah is what Moses taught on the hill overlooking Canaan: Love — love God, obey God, be faithful — choose life.

You recall that Jesus was once asked what the greatest commandment was and you remember how he answered: the greatest commandment is this, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your mind, and with all your strength.” And, he added, there is a second, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” In so answering, Jesus was not declaring anything new; his answer was straight up traditional rabbinic teaching.

There is a story about a rabbi contemporary to Jesus, Rabbi Hillel, the leader of one of the influential schools of Judaism at the time. A story related in the Jewish Talmud tells about a gentile who was curious about Judaism. This man challenged Hillel to explain Jewish law while he (the gentile) stood on one foot. Accepting the challenge, Hillel said: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. That is the whole Torah; the rest is commentary. Now, go and read it!”

Jesus and Hillel, good First Century rabbis, were simply saying what Moses had said to the people of the Hebrews standing on that hill looking into Canaan-land so many centuries before. There are a lot of commandments, a lot of rules, a lot of ordinances . . . but they are simply schoolmasters, disciplinarians teaching an underlying, foundational principle: Love God, obey God, be faithful. To do this is to choose life; to do anything else is to choose death.

Choose life!

L’Chaim! And don’t screw it up!

Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Leave a Reply