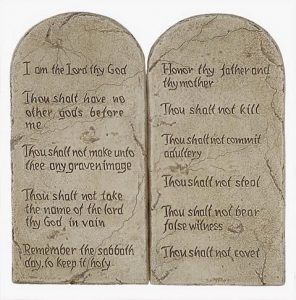

Here they are. The “Big Ten”! The words of Exodus[1] that Right-wing fundamentalists want to chisel in granite and put in American courthouses unless, of course, they prefer the similar (but not quite the same) version in the Book of Deuteronomy.[2]

Here they are. The “Big Ten”! The words of Exodus[1] that Right-wing fundamentalists want to chisel in granite and put in American courthouses unless, of course, they prefer the similar (but not quite the same) version in the Book of Deuteronomy.[2]

My sort of go-to guy on the Old Testament is a Lutheran scholar named Terence Fretheim, who is Professor Emeritus of Old Testament at Luther Seminary, Saint Paul, Minnesota. My first grounding in the Hebrew Scriptures was from a short, two-volume study guide he wrote with co-author Lutheran pastor Darold H. Beekman entitled Our Old Testament Heritage.[3] A couple of years ago, Fretheim wrote a short online commentary on today’s Old Testament lesson in which he said:

The Ten Commandments are not new commandments for Israel (see Exodus 16:22-30), but they are a convenient listing of already existing law for vocational purposes. Moreover, the Commandments were not thought to be transmitted in a never-to-be-changed form. They were believed to require adaptation in view of new times and places.[4]

This is why the version set out in Deuteronomy is slightly different.

Five years ago, Ben Bernanke (who at the time was chairman of the Federal Reserve) gave the baccalaureate address at Princeton University. As he began his speech to the graduating seniors he observed that from the same lectern over the years “any number of distinguished spiritual leaders have ruminated on the lessons of the Ten Commandments.” However, he said, “I don’t have that kind of confidence, and, anyway, coveting your neighbor’s ox or donkey is not the problem it used to be, so I thought I would use my few minutes today to make Ten Suggestions, or maybe just Ten Observations . . . .”[5] Unfortunately, I think, “ten suggestions” is the way many people today think of the Ten Commandments (other than, of course, those Right-wing fundamentalists who want to chisel them in granite and enforce their particular understanding of them on everyone else).

One reason for this might be that very few people actually know the Ten Commandments anymore. I can remember a time when they were said in church every Sunday. The presiding priest would say them in succession (using the Exodus version) and after each except the last, we would reply, “Lord, have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.” After the tenth we would say, “Lord, have mercy upon us, and write all these thy laws in our hearts, we beseech thee.”[6] How many of us now, I wonder, know the Ten Commandments by heart; how many of us can claim that they are “written in our hearts”?

Have ever seen a faithful Muslim praying with beads? The Muslim rosary is called a Tasbih and it consists of thirty-three beads, divided into three sections of eleven. As each bead is “counted” and a phrase such as “God is great” or “Praise to God” is said (in Arabic, of course), the prayer meditates on one of the ninety-nine attributes of Allah named in the Qur’an. These are descriptions of God that we who, like Muslims, are followers of an Abrahamic faith would not disagree with: that God is merciful, compassionate, holy, all-seeing, benevolent, wise, and so on.

A Canadian Catholic journalist, David Warren, noting the memory work that faithful recitation of the Tasbih prayers requires, compares the faithful Muslim to the modern North American Christian and his or her appreciation of the Ten Commandments:

I would also say that ten points are easier to remember than ninety-nine. (And that, two points are easier still, when it comes to that in Saint Matthew’s Gospel.)

What I find rather astonishing is that we have come to a time, not when the Ten Commandments are denied, but when a considerable part of the population has no idea what they might be. And this, notwithstanding they can read and write, after a fashion. And vote, et cetera.[7]

Warren’s closing jab there, about voting, brings me back to Professor Fretheim.

Remember what he said, that the Ten Commandments were nothing new for the Hebrews. Rather they were a “convenient list” of existing laws flexibly put together “for vocational purposes,” adaptable to changing circumstances. Later in his commentary, he expanded on this, adding:

The focus of the commandments is vocational, to serve the life and health of the community, to which end the individual plays an important role. The first commandment lays a claim: How you think about God will deeply affect how you think about and act toward your neighbor.[8]

Which brings us to the Gospel lesson in which John the Evangelist tells us the odd story of Jesus venting his anger over what he considered the desecration of the Temple, and then referring to himself, or at least to his body, as a temple which, if torn down, will be rebuilt in three days. I love the comment of one scholar who said of this metaphor: “If you are a trusting reader of scripture, you are waiting for this to make sense. If you are suspicious one, you may already have left the building.”[9]

The New Interpreter’s Bible commentary helps us a bit to make sense of this by noting

Since for Judaism the Temple is the locus of God’s presence on earth, [this metaphor] suggests that Jesus’ body is now the locus of God. [It] recalls [Jesus’ earlier statement that] the Son of Man replaces Jacob’s ladder as the locus of God’s interaction with the world.[10]

While I find that a bit helpful, I find I can connect with the metaphor better through its extension in some of the letters of St. Paul where he applies it not to Jesus, but to Jesus’ followers both individually and corporately.

In the First Letter to the Corinthians (from the first chapter of which today’s epistle lesson found in your bulletin insert is taken), Paul reminds his readers, “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?”[11] And again, a bit later in the same letter, he asks, “Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, which you have from God, and that you are not your own?”[12] The interesting thing here is that, in the Greek, the “yous” are plural. If we were to use Southern vernacular, we’d render this as “Do y’all not know that y’all are God’s temple?” It is the community of the church, which elsewhere in this letter (and also in the Letter to the Ephesians) Paul explicitly calls “the body of Christ,”[13] which is God’s temple, a community whose “life and health” the individual member serves, vocationally formed and fitted (as Professor Fretheim said) by the Ten Commandments.

Although Peter does not use the word temple in his first catholic epistle, he draws on the same understanding (indeed, using a related metaphor we find in today’s epistle lesson) when he writes:

Come to him, a living stone, though rejected by mortals yet chosen and precious in God’s sight, and like living stones, let yourselves be built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. For it stands in scripture: “See, I am laying in Zion a stone, a cornerstone chosen and precious; and whoever believes in him will not be put to shame.” To you then who believe, he is precious; but for those who do not believe, “The stone that the builders rejected has become the very head of the corner,” and “A stone that makes them stumble, and a rock that makes them fall.” They stumble because they disobey the word, as they were destined to do.[14]

In masonry, and by that I mean the actual art and science of building edifices with stone such as this church building in which we are sitting, the stones to which Peter refers in his spiritual housebuilding metaphor, are called “ashlars.” In Freemasonry, ashlars are used as a metaphor for personal improvement. Freemasons are taught that the “rough” ashlar is a stone as taken directly from the quarry while a “smooth” or “perfect” ashlar is a stone that has been smoothed and dressed by a master stonemason. Allegorically, the perfect ashlar represents a person who, through education and diligence, lives an upstanding life.[15]

There is something to be said for that Masonic metaphor! Frankly, it echoes very closely Peter’s admonition to let ourselves “like living stones . . . be built into a spiritual house.” We can, I think, extend the metaphor to suggest that the Ten Commandments, this flexible and adaptable summary of God’s behavioral expectations of us, are the tools by which we are dressed to be fitted into that temple. Although it may take more than three days, learning, doing our best to follow, and being deeply affected by the Ten Commandments, fits us to serve the life and health of the community.

It is not appropriate to chisel the Ten Commandments into granite and put them in our secular courts, and not just because of our Constitutional separation of church and state. It is not appropriate to chisel them into blocks of stone because though they may have originally been “cast in stone” and given to Moses on Mt. Sinai, they were meant (as Professor Fretheim said) to be flexible and adaptable. Even more so, it is not appropriate for us to chisel them into blocks of stone because we are called to let them chisel us into stones fit for God’s temple, the body of Christ.

Would you open your prayer books to page 317, please? You will find there the Decalogue, the Ten Commandments, in that form which with our celebrations of the Holy Eucharist used to begin before the adoption of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer. Let us pray them together, in that old-fashioned way, that God will write these laws in our hearts and fit us for that “house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.”[16]

God spake these words, and said:

I am the Lord thy God who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have none other gods but me.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven image, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or in the water under the earth; thou shalt not bow down to them, nor worship them.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Remember that thou keep holy the Sabbath day.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Honor thy father and thy mother.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt do no murder.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt not steal.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Lord have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law.

Thou shalt not covet.

Lord have mercy upon us, and write all these thy laws in our hearts, we beseech thee.[17]

Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Third Sunday in Lent, March 4, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector. (This sermon references Freemasonry; Fr. Funston is an endowed, the largely inactive, member and Past Master of Medina Lodge No. 58, F&AM.)

(The lessons for the service are Exodus 20:1-17; Psalm 19; 1 Corinthians 1:18-25; and St. John 2:13-22. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Notes:

[1] Exodus 20:1-17 (Return to text)

[2] Deuteronomy 5:6-20 (Return to text)

[3] Terence Fretheim & Darold Beekman, Our Old Testament Heritage, Vols. 1 & 2 (Augsburg Press, Minneapolis:1970) (Return to text)

[4] Commentary on Exodus 20:1-17, Working Preacher, March 8, 2015, online (Return to text)

5] The Ten Suggestions, The Federal Reserve, June 2, 2013, online (Return to text)

[6] The Book of Common Prayer 1928, pages 68-69. Cf. The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pages 317-18 (Return to text)

[7] The Ten “Suggestions”, The Catholic Thing, August 7, 2015, online (Return to text)

[8] Op. cit. (Return to text)

[9] Mary Hinkle Shore, Commentary on John 2:13-22, Working Preacher, March 4, 2018, online (Return to text)

[10] Gail R. O’Day, The Gospel of John, The New Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. IX (Abingdon, Nashville:1995), page 544 (Return to text)

[11] 1 Corinthians 3:16 (Return to text)

[12] 1 Corinthians 6:19 (Return to text)

[13] 1 Corinthians 12:27; Ephesians 4:12. Cf. Romans 12:5 (Return to text)

[14] 1 Peter 2:4-8 (Return to text)

[15] Ashlar, Wikipedia, online (Return to text)

[16] 2 Corinthians 51 (Return to text)

[17] The Book of Common Prayer 1979, pages 317-18 (Return to text)

Leave a Reply