====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on Maundy Thursday, April 13, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are from the Revised Common Lectionary: Exodus 12:1-14; Psalm 116:1,10-17; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26; and St. John 13:1-17,31b-35. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Today, we take part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Today, we take part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.

The audience of worship is God. The one, holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, God is the audience. We, all of us, are the actors. We, all of us, are the cast.

So, here we are….

Act One, Scene One: The curtain rises. We see a group of people gathered in an upper room somewhere in Jerusalem.

A meal is in progress… we wonder if it might be a seder, the ritual meal of remembrance of the Passover. We don’t really know; the playwrights have not made this clear and the theater critics, the scholars, debate the issue.

Three of the story-tellers suggest that it is. Luke and Matthew based their stories on Mark’s, so to be honest there aren’t three stories, there’s only one that would make us think that this supper is a seder.

However, the fourth, John, tells the tale very differently. John doesn’t even seem to care about the dinner – he spends no time at all describing the meal; for him, it’s not important. What’s important is what happened afterward.

So as we continue this three-act drama of redemption let’s just assume that that Matthew, Mark, and Luke are correct and what we see in this first scene of the first act is, indeed, a seder.

Those present are prepared to do all that is laid out in the instructions in the book of Exodus; they have worn their sandals; they carry their staffs; they expect to eat of roasted lamb and unleavened bread and bitter herbs. They anticipate spending the night in remembrance of that which happened generations before in Egypt. If we can imagine that they celebrate as modern Jews celebrate, they are gathered in that upper room, those serving the meal coming and going, and a breeze blowing through the open windows. They are following along in their prayer books, the Haggadah; they expect the youngest among them to ask the questions, beginning with “Why is this night different from all other nights?” They know that the head of the household, their rabbi Jesus, will answer those questions in the prescribed way and tell the story of the Passover.

So, when the youngest asks “Why do we eat the broken matzah?” they expect Jesus to answer “This is the bread of our affliction; the unleavened bread of poverty, baked and eaten in haste,” but instead he takes the bread, brakes it and says, “This bread is my body, given for you.”

They look up startled, glancing at one another, murmuring to each other, “What is he talking about? That’s not here! That’s not the right answer. Where is he? What page is he on?” But the moment passes, the meal moves on.

At the end he takes up the fourth and final cup of wine, the kiddush cup, which recalls God’s promise, “I will acquire you as a nation; you will be my people and I will be your God.” As before, they expect Jesus to say the prescribed prayer, “Blessed are you, O Lord our God, sovereign of the universe, creator of the fruit of the vine,” but instead they hear, “This cup is my blood!” “What?!” They look at one another in disbelief. “What is he saying???”

It is for Jesus and his disciples one of those fleeting opportunities when, because of the pupils’ confusion or frustration or grasping for understanding, the teacher can pass on to the students new information, new values, new moral understanding, a new behavior, a new skill, a new way of seeing and coping with reality; it is what we have come to call “the teachable moment” and so he teaches, yet again, “Remember! Remember,” he says, “Love one another as I have loved you.”

The curtain falls as Jesus continues to teach; the disciples look mystified.

Act One, Scene Two: The curtain rises again. We see the same group of people gathered in the same upper room somewhere in Jerusalem.

The meal is over, the dishes have been cleared. The disciples are arguing among themselves about who is the greater among them. Jesus looks frustrated and troubled; the teachable moment has passed and the disciples clearly have not understood! They just haven’t gotten it.

“Look,” he says, “the greatest among you must become like the youngest, and the leader like one who serves. For who is greater, the one who is at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one at the table? But I am among you as one who serves. Here, let me show you what I mean.” Getting up from the table, he takes off his robe, picks up a basin of water and a towel, and begins to wash and dry their feet.

As many of you know, I am a fan of science fiction, so when I hear about towels, one of the first things I think of is the late Douglas Adams’ hilariously funny novel, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The book begins seconds before Earth is demolished to make way for a galactic freeway, when the protagonist Arthur Dent is plucked off the planet by his friend Ford Prefect, a researcher for a revised edition of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy who has been posing for the last 15 years as an out-of-work actor. The one thing Prefect makes sure that Dent brings with him is a towel. Quoting from the guidebook, he explains that a towel is the one, crucial, indispensable necessity that the intergalactic traveler must bring along on any journey:

A towel (says The Hitchhiker’s Guide) is about the most massively useful thing an interstellar hitchhiker can have . . . . you can wrap it around you for warmth . . . . you can lie on it on . . . brilliant marble-sanded beaches . . . . you can sleep under it beneath the stars . . . . use it to sail a mini-raft down a slow river . . . . wet it for use in hand-to-hand combat; wrap it round your head to ward off noxious fumes . . . . you can wave your towel in emergencies as a distress signal, and of course dry yourself off with it if it sill seems to be clean enough.

Any man who can hitch the length and breadth of the galaxy, rough it, slum it, struggle against terrible odds, win through, and still know where his towel is is clearly a man to be reckoned with.

John tells us that Jesus made use of the towel to dry the disciples’ feet and then said, “I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you.” It has occurred to me that The Hitchhiker’s Guide suggests many other ways in which we might use a towel in following Jesus’ lead.

When we baptize someone here at St. Paul’s Parish, the altar guild supplies towels for them to be dried with; I often joke about getting those towels back. But now it seems to me that we might better give them to the newly baptized with an admonition to follow Jesus’ example of loving service. The towel of service just might be the one, crucial, indispensible necessity that the Christian traveler should bring along on his or her journey through life. It just may be the most massively useful thing we can have as we serve others. We can wash and dry their feet; we can wrap them in warmth; we can provide a comfortable place to sleep; we can help them on a journey; we can protect them; we can signal to them and for them in emergencies; we can clothe the naked, swaddle a baby, comfort the sick. I’m sure you can come up with many more uses, small and large, for a towel and, by extension, for your heart, for your life, and for your willing hands.

That Jesus made use of the towel in the context of the Lords’ Supper is a really important point. There used to be what some thought of as a silly and useless bit of priestly vesture worn at Communion called a “maniple.” It looked sort of like a short stole and was made of the same material as the stole and chasuble. It was worn over the left forearm and looked like, and in fact was meant to symbolize, the sort of towel or table napkin often worn by the wait-staff in fancy restaurants, a symbol of service. Anglican clergy stopped wearing maniples long ago and Roman Catholic priests were allowed to discontinue them in 1967, one of the minor reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

In abandoning that symbolic vestment, however, we may have lost a reminder that, in addition to being called to follow Jesus along the way of the cross, we are also called to follow him in his use of the towel! Just as Jesus said, “Take up your cross and follow me,” he might also have said, “Take up your towel and follow me.” In fact, he did when he said, “I have set you an example, that you should also do as I have done to you.”

Perhaps we no longer use the maniple as a priestly vestment because the ministry of Christian servanthood which it represents is not limited to clergy; it is the ministry of all baptized people. “Will you seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving your neighbor as yourself?” we are asked in the liturgy of baptism, and every person present answers, “I will, with God’s help.” This servant ministry is one which we all share, just as this meal of Bread and Wine, of Christ’s Body and Blood, is one which we all share.

The disciples, however, don’t get the opportunity to serve one another, for this second scene ends with Jesus, visibly agitated, declaring, “One of you will betray me.” As the curtain goes down, the disciples are looking puzzled and Judas Iscariot is leaving.

Act One, Scene Three: The curtain rises again. We see a garden and an olive grove just outside of Jerusalem. Jesus is there, accompanied by Peter, James, and John. “Stay here,” he tells them, “Stay awake while I go over there to pray.” As they settle themselves, he moves away from them, and collapses in a heap, sobbing: “O God … Father, let this pass!”

Three times he returns to find them asleep; three times they rise looking sheepish and embarrassed; twice he tells them again to try to stay awake as he goes away still pleading with God for a way out. “Enough,” he says the third time, “Enough! We’re leaving.”

When they look back on that night, how must they feel? When we look back, how should we feel? Poet Mary Oliver offers a glimpse in her poem Gethsemane:

The grass never sleeps.

Or the roses.

Nor does the lily have a secret eye that shuts until morning.

Jesus said, wait with me. But the disciples slept.The cricket has such splendid fringe on its feet,

and it sings, have you noticed, with its whole body,

and heaven knows if it ever sleeps.Jesus said, wait with me. And maybe the stars did,

maybe the wind wound itself into a silver tree,

and didn’t move, maybe the lake far away,

where once he walked as on a blue pavement,

lay still and waited, wild awake.Oh the dear bodies, slumped and eye-shut, that could not

keep that vigil, how they must have wept,

so utterly human, knowing this too

must be part of the story.

Yes, this too, our utterly human inability to fully keep company with our Lord, this too must be part of the story when it is told, part of the third scene of the first act of this drama that is retold again and again. This minor, little betrayal is as much a part of the story as Judas’ treachery which now plays out.

Scene Three ends as Jesus is arrested and taken away off-stage. In the wings, a trivial side-story plays out as Judas dies, either by hanging himself (as Matthew asserts) or by falling and suffering some sort of rupture (as Luke portrays in the Book of Acts). In any event, Judas dies and, in the church’s eyes, is condemned.

The Scottish poet Robert Williams Buchanan, in a very long elegy entitled The Ballad of Judas Iscariot, tells the tale of the soul of Judas carrying his body in search of a burial place, only to have it rejected by even the worst of places in all creation. Eventually, he comes to a banquet hall where a wedding feast is waiting to get started. The guests (that is, the church), recognizing Judas, demand that he be “scourged away,” but the Bridegroom has a different idea:

The Bridegroom stood in the open door,

And he waved hands still and slow,

And the third time that he waved his hands

The air was thick with snow.And of every flake of falling snow,

Before it touched the ground,

There came a dove, and a thousand doves

Made sweet sound.‘Twas the body of Judas Iscariot

Floated away full fleet,

And the wings of the doves that bare it off

Were like its winding-sheet.‘Twas the Bridegroom stood at the open door,

And beckon’d, smiling sweet;

‘Twas the soul of Judas Iscariot

Stole in, and fell at his feet.“The Holy Supper is spread within,

And the many candles shine,

And I have waited long for thee

Before I poured the wine!”The supper wine is poured at last,

The lights burn bright and fair,

Iscariot washes the Bridegroom’s feet,

And dries them with his hair.

We sometimes use a Scottish invitation to Communion which comes from the ecumenical monastic community on the island of Iona:

The table of bread and wine is now to be made ready.

It is the table of company with Jesus,

And all who love him.

It is the table of sharing with the poor of the world,

With whom Jesus identified himself.

It is the table of communion with the earth,

In which Christ became incarnate.

So come to this table,

You who have much faith

And you who would like to have more;

You who have been here often

And you who have not been for a long time;

You who have tried to follow Jesus,

And you who have failed;

Come. It is Christ who invites us to meet him here.

All who have faith; all who would like to have more; all who have been to Communion often; all who have not been for a long time; all who have tried to follow Jesus (in the way of the cross or the way of the towel); all who have failed to do so. In other words, as John of Patmos witnessed in his vision recorded in the Book of Revelation, everyone is called to the Supper of the Lamb; everyone is invited to the Wedding Feast! Even the disciples who fell asleep in the garden; even Judas Iscariot!

In this, the first act of the drama of redemption, Jesus has gathered his disciples. He has gathered us at the table that in the upper room. He has shared Bread and Wine. He washed and dried feet. He has given us the New Commandment: “Love one another.” He has said, “I have set you an example.” He might well have said, “Take up your towel and use it.”

The Hitchhiker’s Guide says your towel can be used as a signal. So take up your towel; wave it so that all may see, and when you have their attention, invite them into this drama of redemption in which, tonight, we witness and take part in the first of three acts. Say to them, with Jesus, “Come! Come to this table! . . . . We have waited long for thee!”

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

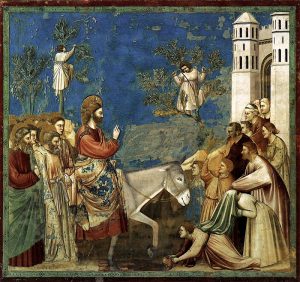

Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.

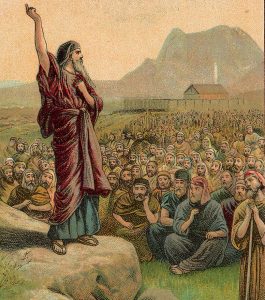

Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.  The Book of Deuteronomy tells us that when the long Exodus journey of the People of the Hebrews ended, just before they were to cross over into the Promised Land, Moses delivered a farewell address. He was not going to be going into the new land with them.

The Book of Deuteronomy tells us that when the long Exodus journey of the People of the Hebrews ended, just before they were to cross over into the Promised Land, Moses delivered a farewell address. He was not going to be going into the new land with them.  “The Lord called me before I was born, while I was in my mother’s womb he named me.” (Isa. 49:1b) What a powerful statement that is that the prophet makes in today’s reading. We name this prophet Isaiah; scholars name him Deutero-Isaiah or Second Isaiah. We don’t really know his name . . . but God did! God named him before he was born. Gave him personhood and human identity.

“The Lord called me before I was born, while I was in my mother’s womb he named me.” (Isa. 49:1b) What a powerful statement that is that the prophet makes in today’s reading. We name this prophet Isaiah; scholars name him Deutero-Isaiah or Second Isaiah. We don’t really know his name . . . but God did! God named him before he was born. Gave him personhood and human identity. We are here tonight for two reasons. First, because this is the Feast of the Epiphany, one of the major feasts of the Christian Church and one we too often ignore, and second, because this is the inaugural event of our Year of Celebration during which we will mark the 200th anniversary of the founding of this parish.

We are here tonight for two reasons. First, because this is the Feast of the Epiphany, one of the major feasts of the Christian Church and one we too often ignore, and second, because this is the inaugural event of our Year of Celebration during which we will mark the 200th anniversary of the founding of this parish.  Today on the secular calendar is New Year’s Day, but that’s not true in the church. We celebrated a new church year several weeks ago on the First Sunday of Advent. In the church, January 1, being eight days after the Feast of the Incarnation, is the day on which we celebrate Jesus’ Jewishness. We call it, these days, the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus; it was formerly called the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ because that is what Luke’s Gospel tells us was done. It was a very Jewish thing to do.

Today on the secular calendar is New Year’s Day, but that’s not true in the church. We celebrated a new church year several weeks ago on the First Sunday of Advent. In the church, January 1, being eight days after the Feast of the Incarnation, is the day on which we celebrate Jesus’ Jewishness. We call it, these days, the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus; it was formerly called the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ because that is what Luke’s Gospel tells us was done. It was a very Jewish thing to do. I was in the pet supply aisle at Giant Eagle several days ago getting food for the Archbishop (that’s our black cocker spaniel, Lord Dudley of Ballycraic, the Archbishop Canine of Montville) when I found, right in front of the Beneful which is his favorite meal, a bin filled with these: dog toys in the likeness of a lamb dressed for Christmas. And not just any lamb! This is Lamb Chop, the somewhat snarky puppet introduced to the world by the late Shari Lewis in 1957.

I was in the pet supply aisle at Giant Eagle several days ago getting food for the Archbishop (that’s our black cocker spaniel, Lord Dudley of Ballycraic, the Archbishop Canine of Montville) when I found, right in front of the Beneful which is his favorite meal, a bin filled with these: dog toys in the likeness of a lamb dressed for Christmas. And not just any lamb! This is Lamb Chop, the somewhat snarky puppet introduced to the world by the late Shari Lewis in 1957. Which brings me to the fourth and last bit of poetry our Christmas Lamb Chop brought to mind, which is a song Lamb Chop and Shari Lewis taught their viewers during the 1992 season of the PBS show Lamb Chop’s Play-Along. Some of you may know the song and can sing along:

Which brings me to the fourth and last bit of poetry our Christmas Lamb Chop brought to mind, which is a song Lamb Chop and Shari Lewis taught their viewers during the 1992 season of the PBS show Lamb Chop’s Play-Along. Some of you may know the song and can sing along: In these few verses, Matthew opens up for us the complexity of Joseph as a human being. He hints at, and we can imagine, Joseph’s distress, his sense of betrayal, his disappointment, and all the other emotions he must have experienced. We can imagine also the fear and hurt that Mary probably would have felt as she and her betrothed sorted out the complications caused by the divine intrusion into their relationship.

In these few verses, Matthew opens up for us the complexity of Joseph as a human being. He hints at, and we can imagine, Joseph’s distress, his sense of betrayal, his disappointment, and all the other emotions he must have experienced. We can imagine also the fear and hurt that Mary probably would have felt as she and her betrothed sorted out the complications caused by the divine intrusion into their relationship. Most of the time when we hear this story of John’s disciples coming to Jesus we focus on John’s question – “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” (Mt 11:3) – and on Jesus’ answer to it which is neither a “yes” nor a “no” but a pointing to the evidence – “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them” (Mt 11:5).

Most of the time when we hear this story of John’s disciples coming to Jesus we focus on John’s question – “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” (Mt 11:3) – and on Jesus’ answer to it which is neither a “yes” nor a “no” but a pointing to the evidence – “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them” (Mt 11:5).