====================

A “Rector’s Reflection” offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector, in the April 2016 edition of the parish newsletter, St. Paul’s Epistle.

====================

It’s April! When did that happen?

It’s April! When did that happen?

The Anglo-Saxons called April êastre-monaþ. (That funny looking letter at the end is called a “thorn” and is pronounced like “th”.) This literally means “easter month” and April was called this because it was sacred to the goddess Eostre. According the Venerable Bede (a very early English historian) this is why in the English language we call the feast and season of Christ’s Resurrection “Easter” rather than some variation of the Latin word for “Passover” which is most common among European languages. Of course, this is one of those oddball years when Easter did not, in fact, fall during the month of April.

In 1980, however, Easter fell on April 6. Why would I know this? Because Evelyn and I were married during April, 1980. On Saturday, April 12, in fact. It was the Saturday after Easter Sunday. For some reason, we had wanted to get married on March 15. Thirty-six years later I cannot for the life of me remember why we wanted to get married on the Ides of March, but that was the date. I went to see my parish priest, Fr. Karl Spatz, about that and he just looked at me with an expression of distaste: “That’s during Lent,” he said. “You don’t want to get married during Lent.” He was (and I wasn’t yet) a very high church Anglo-Catholic. So, we got married on the first available Saturday after Easter Sunday.

Here’s a good thing about getting married on Saturday in Easter Week: the Easter flowers and lilies are still really lovely and in full bloom. We had a lovely wedding and we’ve had a lovely marriage and I’m very grateful for it all. Fr. Karl was probably right to encourage us to not get married during Lent; Easter Season was a much better choice.

Easter and April are good times for just about anything. Although we English speakers gave the Anglo-Saxon name to the Feast of the Resurrection, we took the Romans’ name for this month. Etymologists tell us that Aprilis, the original Latin name, is derived from a word meaning “opening,” probably in reference to the opening of leaf and flower buds. To me, however, it suggests Christ’s open tomb.

This time of Resurrection and rebirth is also a time of opening. Opening ourselves to the world around us; opening ourselves to the graces and blessings that come from God the Father. The former news reporter Jon Katz, who writes a blog about living on a farm and raising dogs, and who has written numerous books about dogs, is also a poet. One of his pieces is entitled Open Up, Open Up:

I don’t want to live a small life,

open your eyes,

open your mind,

open your heart.

I have just come from the Dahlia garden,

the first Dahlia kissing me with its blood red mouth,

the wind-winged clouds roaring overhead,

exciting me,

sending me hurtling along, thinking I might perhaps catch a ride,

feel the wind in my face, but no,

the clouds rushed away, places to go.

So I carry these dreams only to you,

One of the last gifts I can ever bring to anyone

in this world filled with love and hope and risk and fear,

so do look at me, listen to me.

Open your soul, let it breathe,

Open your life, open your heart.

I don’t want to live a small life,

of warning and fear.

I don’t want to live that sort of life, either, but it has seemed to me, especially in the current presidential election cycle, that that is exactly the sort of life forced onto all of us by the world in which we live. Palpably since September 11, 2001, we have lived a life “of warning and fear.” That’s nearly a quarter of my life. It’s half of my children’s lives. And it’s the entire lifetime of all of our Sunday School children and many of our youth group members.

Thank God we’ve gotten rid of the color-coded threat-level gauges the government at one time encouraged every news service to broadcast, but even without those the world of warning and fear prevails. Much of this arises, I think, from the clash of personal rights and privileges in a society which has become increasingly and destructively individualistic. A former bishop of mine once remarked that it is a small step from insisting on one’s rights to insisting on being right, from insisting on being right to insisting on being in control, and that being in control is not meant for any of us who claim to follow Jesus.

Consider these admonitions:

“If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me.” (Jesus in Luke 9:23)

“For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” (Jesus in Mark 8:35)

“Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves.” (Paul writing in Philippians 2:3)

For the sake of openness to one another, we are not to insist on our own individual rights, but rather concern ourselves with the needs and well-being of others. Were we to do that, there would be no need for warnings and fears. We have been assured of that by God himself who constantly in both Old and New Testaments, through prophets, through apostles, through Jesus himself sends the same message:

“Moses said to the people, ‘Do not be afraid . . . .'” (Exodus 20:20)

“Be strong and bold; have no fear or dread . . . .” (Deut. 31:6)

“The Lord is at my side, therefore I will not fear.” (Psalm 118:6, BCP)

“Say to those who are of a fearful heart, ‘Be strong, do not fear!'” (Isaiah 35:5)

“Do not fear, only believe.” (Jesus in Mark 5:36)

“Do not be afraid, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.” (Jesus in Luke 12:32)

“So we can say with confidence, ‘The Lord is my helper; I will not be afraid. What can anyone do to me?'” (Letter to the Hebrews 13:6)

When Evie and I got married, the current Book of Common Prayer had been fully official for less than a year (it was ratified by the 66th General Convention in September of 1979). Its marriage vows, however, were and are ancient and revered. We promised, as all marrying couples promise, to take one another as spouses “to have and to hold from this day forward, for better for worse, for richer for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish.” In a word, we committed, as do all married couples, to be open to one another in all circumstances.

Like all sacraments, the sacrament of marriage is “an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace.” The outward and visible sign in marriage is the couple, the two people themselves, and the inward and spiritual grace they are a sign of is exactly the sort of God-empowered interpersonal openness that conquers warnings and fears. If two people can live together in this way, says this sacramental sign, then so can all people.

We’ve been able to do it for 36 years. For that I am grateful to God . . . and especially grateful to Evelyn. In this month of Resurrection, rebirth, and openness, I encourage you to think on that (and on all married couples who have done likewise) and realize the promise of the sacrament’s grace, the promise of openness: God’s promise that none of us needs to “live a small life, of warning and fear.”

“Do not be afraid, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.”

It’s April! Claim the openness! Claim the kingdom!

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

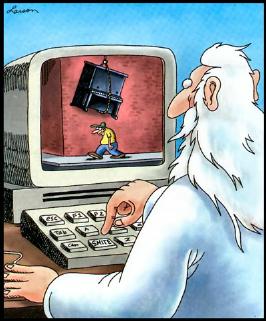

Some years ago the cartoonist Gary Larson published a cartoon of an old white-bearded judgmental God sitting at his computer terminal watching the live-streaming video of some feckless and unsuspecting sinner walk under a piano suspended from a crane while God’s finger is poised over a button on the keyboard labeled “Smite”. This seems to be the God these folk are describing to Jesus, a bookkeeper god who keeps a running tally of the good things and bad things we may do and then at some arbitrary point pushes the “Smite” button and puts paid to our cosmic account. This is the god of those who ask “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” when something bad happens to them. This is the god of those who say “Everything happens for a reason” when something bad happens to someone else. This is the picture of God that Jesus rejects utterly and completely.

Some years ago the cartoonist Gary Larson published a cartoon of an old white-bearded judgmental God sitting at his computer terminal watching the live-streaming video of some feckless and unsuspecting sinner walk under a piano suspended from a crane while God’s finger is poised over a button on the keyboard labeled “Smite”. This seems to be the God these folk are describing to Jesus, a bookkeeper god who keeps a running tally of the good things and bad things we may do and then at some arbitrary point pushes the “Smite” button and puts paid to our cosmic account. This is the god of those who ask “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” when something bad happens to them. This is the god of those who say “Everything happens for a reason” when something bad happens to someone else. This is the picture of God that Jesus rejects utterly and completely. As many of you know, Evie and I were privileged to make a pilgrimage to the holy places of Palestine summer before last and one of the sites we visited was Mt. Tabor, the traditional “Holy Mountain” on which the Transfiguration is believed to have taken place.

As many of you know, Evie and I were privileged to make a pilgrimage to the holy places of Palestine summer before last and one of the sites we visited was Mt. Tabor, the traditional “Holy Mountain” on which the Transfiguration is believed to have taken place.

A Native American proverb instructs us, “When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced; live your life in a manner that when you die, the world cries and you rejoice.” Today, on what would have been Sheryl Ann King’s 48th birthday, the world (you and me and everyone who knew and loved Sherry) is crying, but Sherry is rejoicing. “If you loved me,” Jesus told his followers, “you would rejoice that I am going to the Father” (Jn 14:28); we who love Sherry, let us rejoice (even through our tears) that she, too, has gone to the Father.

A Native American proverb instructs us, “When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced; live your life in a manner that when you die, the world cries and you rejoice.” Today, on what would have been Sheryl Ann King’s 48th birthday, the world (you and me and everyone who knew and loved Sherry) is crying, but Sherry is rejoicing. “If you loved me,” Jesus told his followers, “you would rejoice that I am going to the Father” (Jn 14:28); we who love Sherry, let us rejoice (even through our tears) that she, too, has gone to the Father. It’s the Second Sunday of Advent so according to our lectionary tradition, we hear the words of John the Baptizer, the voice of one crying in the desert, calling us to clean up the roadways and build a straight path for God’s coming. We are all familiar with the Baptizer. He’s some sort of cousin of Jesus. He’s a bit of a wild man; he lives in the wilderness wearing rough clothing and eating only what foods he can pick from desert plants and animals, “locusts and wild honey” is the way the evangelists put it. This year we hear Luke’s version of John’s story.

It’s the Second Sunday of Advent so according to our lectionary tradition, we hear the words of John the Baptizer, the voice of one crying in the desert, calling us to clean up the roadways and build a straight path for God’s coming. We are all familiar with the Baptizer. He’s some sort of cousin of Jesus. He’s a bit of a wild man; he lives in the wilderness wearing rough clothing and eating only what foods he can pick from desert plants and animals, “locusts and wild honey” is the way the evangelists put it. This year we hear Luke’s version of John’s story. The death of anyone important in our lives is a tragic and painful thing, even if the relationship was strained or even broken. This is especially so when a parent dies and, for some reason, more so when that parent is our father, perhaps because we use that metaphor of fatherhood to explain God’s relationship to us. Whenever someone’s father passes away, I cannot help but remember the poem by the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night:

The death of anyone important in our lives is a tragic and painful thing, even if the relationship was strained or even broken. This is especially so when a parent dies and, for some reason, more so when that parent is our father, perhaps because we use that metaphor of fatherhood to explain God’s relationship to us. Whenever someone’s father passes away, I cannot help but remember the poem by the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night: