====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Eighth Sunday after Pentecost, July 30, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are from Proper 12A (Track 1) of the Revised Common Lectionary: Genesis 29:15-28; Psalm 128; Romans 8:26-39; and St. Matthew 13:31-33,44-52. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Have you ever had a friend try to tell you about going to see a stand-up comedian’s show? When I lived in Las Vegas, this happened fairly often in my workplace. Someone would go to see the late Robin Williams, or Jon Stewart (before he took over the Daily Show), or any of several who made regular appearances on the Strip, and then on Monday morning over coffee they would try to tell us how funny the show was.

Have you ever had a friend try to tell you about going to see a stand-up comedian’s show? When I lived in Las Vegas, this happened fairly often in my workplace. Someone would go to see the late Robin Williams, or Jon Stewart (before he took over the Daily Show), or any of several who made regular appearances on the Strip, and then on Monday morning over coffee they would try to tell us how funny the show was.

Jokes with punchlines, if my co-worker had a good memory and reasonable sense of comedic timing, could be pretty funny. But one-liners . . . not so much. One-liners are pretty much a you-had-to-be-there sort of thing; funny at the time and in the context, but they lose something in the retelling.

This section of Matthew’s Gospel always feels to me like that’s what the author is trying to do here. Just before the bit that we read this morning, Matthew has told the longer stories we heard last Sunday and the week before, the agricultural parables of the sower and of the wheat and weeds, together with their explanatory punchlines. Now he launches into the one-liners that Jesus told: The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed, like yeast, like a treasure, like a net, like a peanut M&M, like an Oktoberfest, like plaster that fell into a pipe organ. (OK, the last three aren’t from Jesus, but they could have been.)

These quick parables are offered in rapid-fire, quick succession, without explanation and without time for the reader or hearer to ponder or respond to them. That pondering and response comes later, if it comes at all.

Last week, Philip Yancey, a widely-respected and prolific Christian author, currently an editor-at-large at the magazine Christianity Today, published an op-ed piece in The Washington Post, entitled “The Death of Reading Is Threatening the Soul” (Washington Post, 7/21/2017) He began it with these words:

I am going through a personal crisis. I used to love reading. I am writing this blog in my office, surrounded by 27 tall bookcases laden with 5,000 books. Over the years I have read them, marked them up, and recorded the annotations in a computer database for potential references in my writing. To a large degree, they have formed my professional and spiritual life.

“I used to read three books a week,” he said. But these days that is practically impossible for him, as it may be for many of us. “The Internet and social media have trained [our] brain[s] to read a paragraph or two, and then start looking around.” These rapid, one-liner parables seem almost designed for the social media age; nearly all of them in today’s reading can be trimmed and edited into the 140-character limit of a Twitter tweet (a couple don’t even need to be edited).

But these are not tweets! They need to be taken and understood in context; it’s just that the context isn’t supplied by the surrounding text, in this case Matthew’s gospel, as it is with most short quotations. The context of these short parables is the same as the context of one-liners in a comedy routine that fall flat when someone tries to tell them in the office on Monday morning; the context is in the moment of the telling and the hearing, and for us in the modern world reading Matthew’s re-telling of the one-liners, for us who are not sitting on the Galilean hillside in the moment of telling, our own hearing is the most important element.

Philip Yancey’s op-ed article was a plea to modern Christians to do the “hard work of focused concentration on reading.” He drew on the findings of modern neuroscience that it “actually takes less energy to focus intently than to zip from task to task. After an hour of contemplation, or deep reading, a person ends up less tired and less neurochemically depleted, thus more able to tackle mental challenges.” What Yancey (drawing on the work of writer Sven Birkets) calls “deep reading” “requires intense concentration, a conscious lowering of the gates of perception, and a slower pace;” this is what is needed to build the context for hearing the parables of Jesus. Says Yancey:

Modern culture presents formidable obstacles to the nurture of both spirituality and creativity. As a writer of faith in the age of social media, I host a Facebook page and a website and write an occasional blog. Thirty years ago I got a lot of letters from readers, and they did not expect an answer for a week or more. Now I get emails, and if they don’t hear back in two days they write again, “Did you get my email?” The tyranny of the urgent crowds in around me.

If I yield to that tyranny, my life fills with mental clutter. Boredom, say the researchers, is when creativity happens. A wandering mind wanders into new, unexpected places.

A wandering, creative mind, a mind filled with the products of deep reading rather than cluttered by the superficial demands of “the tyranny of the urgent,” is the context in which the rapid-fire, quick-delivery parables in today’s Gospel become capable of understanding.

“What then are we to say about these things?” asks Paul in today’s reading from the Letter to the Romans. He is, of course, referring to what he had earlier called “the sufferings of this present time,” (v. 18) not to Jesus’ parables. The question, however, applies equally. What are we to say about these parables? How can we say anything if we do not understand them? And how are we to understand them if we have not equipped our minds with the deep reading and varied experience needed to provide the context for our hearing? “Let anyone with ears hear,” says Jesus at the end of many parables; developing our imaginations and our creativity through study and experience is the way we grow those ears. It is the way we give context to these tweet-like one-liners that the kingdom of heaven is like yeast, or a net, or a peanut M&M. (You thought I’d forgotten to come back to that, didn’t you?)

Notice that I didn’t say “reading of Scripture” or “Bible study” is how we grow those ears and develop that context. Reading the Bible is great, but the background to Jesus’ parables, the background to life is much broader than one small collection of 66 (Protestant canon), or 73 (Roman Catholic numbering), or 78 (Easter Orthodox reckoning) varied pieces of literature. I think everyone should read the Bible, but spiritual growth requires the building of a contextual foundation, and that requires reading more than the Bible and experience far beyond the walls of the church.

Our psalm today (Psalm 128) is a paean to family life, to the building of a posterity, to the work of insuring peace for all of God’s people through the faithfulness of the family. It speaks to the idea of work which, like deep reading, takes concentration, and time, and a slower pace. It took Jacob fourteen years of work just to marry his two wives, Leah and Rachel, to begin the family that was the foundation of the People of God; his story works well as a metaphor for the work of building the context for understanding God’s Word. The alternative psalm provided in the Revised Common Lectionary is a selection of verses from Psalm 105 including the admonition to “search for the Lord and his strength; [to] continually seek his face; [and to] remember the marvels he has done.” (vv. 4-5a) Deep reading of all sorts of literature, of science, of fiction, of poetry, of the daily newspaper . . . and experience in many and varied areas of life are among the places and the ways in which we can do that.

So Jesus said that the kingdom of heaven is like a lot of things: a mustard seed, yeast, a pearl of great value, a treasure hidden in a field, a net cast into the sea. And then he asked his closest disciples, “Do you understand these things?” He did not tell them what the parables meant; he simply asked if they knew. “Yes,” they answered. To which he replied, “Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old.” He expected his disciples to have that experience and background, to have done the hard work of building a contextual foundation for understanding and interpreting the metaphors. He asks us the same question and expects of us the same foundation.

I could stand here and tell you what I think is the meaning of seed, yeast, pearl, or net, and I’ve done so many times over the past decade and a half. Do you remember? Probably not. Because the meaning of the metaphors is found only in context and the context for these bullet-point, tweet-like, one-liner-stand-up-routine parables is your own life, your own imagination, your own deep-reading developed creativity. “What then are we to say about these things?” is a question for you to answer.

And when we have each answered it, when we have wrestled with Jesus’ analogies for the kingdom of heaven, we can begin to develop our own.

“The kingdom of heaven is like an Oktoberfest a church congregation offered to the community.” It is an opportunity for the church to invite its neighbors and the residents of its city to enjoy themselves for an afternoon and an evening, to experience good food (maybe a little beer or wine), good company, good music (we hope), and good fellowship. It brings to our community a foretaste of that great party God has promised to everyone through the Prophet Isaiah: “On this mountain the Lord of hosts will make for all peoples a feast of rich food, a feast of well-aged wines, of rich food filled with marrow, of well-aged wines strained clear.” (Is 25:6) We believe and hope that our Oktoberfest, like the St. Nicholas Tea and St. Patrick’s Last Gasp, will be among those “intangible elements” which “significantly contribute to making place and to giving spirit,” which give “give meaning, value, emotion and mystery to” our common life in the City of Medina. (See International Counsel on Monuments and Sites, Quebec Declaration, 4 Oct 2008)

“The kingdom of heaven is like plaster that fell into a pipe organ.” It presented us with the reality of our stewardship of this building and this instrument; it encouraged us to find our own capacity to make music and sing God’s praise even when deprived of our traditional accompaniment. It prompted someone with no current connection to this parish but with fond memories of the organ to make a major donation to its restoration. Plaster falling into the organ reminds us of Psalmist’s encouragement, “Sing praises to God, sing praises; sing praises to our King, sing praises.” (Ps 47:6) The plaster falling into the organ declares with J.S. Bach, “The aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and the refreshment of the soul.” (Quoted in Wilbur, G., Glory and Honor: The Musical and Artistic Legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach, Cumberland House, Nashville:2005, p. 1)

“The kingdom of heaven is like a peanut M&M.” I’m still working on that one. I believe it’s a good metaphor, though. The hard candy shell, the rich milk chocolate, the salty kernel at the center; they all speak to me of the spiritual discoveries of the faith.

“Therefore,” said Jesus, “every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old.” Be like those scribes. Read deeply, experience life, do the hard work of becoming Christian leaders who can mine the wisdom of the ages, both the old and the new, both the religious and the secular, and proclaim the Gospel in context to the people around you. It requires study; it requires imagination and creativity; it requires deep reading and contemplation. But in the end, at the heart of it all, there is great reward; there is understanding, in our own context, of mustard seeds, and yeast, and nets, and pearls, and hidden treasures . . . like the peanut at the center of the M&M.

Amen.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Introductory Comment:

Introductory Comment: Christmas is now done. It ended Friday on Twelfth Night. I am sure than none of you, good Anglican traditionalists that we all are, put away any of your decorations before then, but have by now put them all away.

Christmas is now done. It ended Friday on Twelfth Night. I am sure than none of you, good Anglican traditionalists that we all are, put away any of your decorations before then, but have by now put them all away.  In Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe’s novel of post-colonial political intrigue in Africa, Anthills of the Savannah (1987), one of the characters (echoing Karl Marx’s famous aphorism about religion) opines:

In Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe’s novel of post-colonial political intrigue in Africa, Anthills of the Savannah (1987), one of the characters (echoing Karl Marx’s famous aphorism about religion) opines:

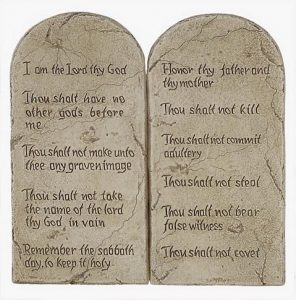

A lawyer asked Jesus a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “’You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

A lawyer asked Jesus a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “’You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” As I pondered our scriptures for today I was struck by how different, how utterly foreign, one might most accurately use the word “alien,” the social landscape of the bible is from our own. We, children of a post-Enlightenment Constitution which makes a clear delineation, almost a compartmentalization, between the civic and the religious, simply cannot quickly envision the extent to which those areas of human existence were entangled and intertwined for those who wrote and whose lives are described in both the Old and New Testaments. I tried to think of an easy metaphor to help illustrate the difference between our worldview and that of either the ancient wandering Hebrews represented by Moses in the lesson from Exodus or of the first Century Palestinians and Romans characterized by Jesus, the temple authorities, and Paul.

As I pondered our scriptures for today I was struck by how different, how utterly foreign, one might most accurately use the word “alien,” the social landscape of the bible is from our own. We, children of a post-Enlightenment Constitution which makes a clear delineation, almost a compartmentalization, between the civic and the religious, simply cannot quickly envision the extent to which those areas of human existence were entangled and intertwined for those who wrote and whose lives are described in both the Old and New Testaments. I tried to think of an easy metaphor to help illustrate the difference between our worldview and that of either the ancient wandering Hebrews represented by Moses in the lesson from Exodus or of the first Century Palestinians and Romans characterized by Jesus, the temple authorities, and Paul. “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”

“The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”  I’m wearing an orange stole today and a couple of you asked me on the way into church, “What season is orange?” Well, it’s not a seasonal stole … although I suppose we could say it commemorates the season of unregulated and out of control gun violence. A few years ago, a young woman named Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed in Chicago; her friends began wearing orange, like hunters wear for safety, in her honor on her birthday in June. A couple of years ago, Bishops Against Gun Violence, an Episcopal group, became a co-sponsor of Wear Orange Day and some of us clergy here in Ohio decided to make and wear orange stoles on the following Sunday. Our decision got press notice and spread to clergy of several denominations all over the country.

I’m wearing an orange stole today and a couple of you asked me on the way into church, “What season is orange?” Well, it’s not a seasonal stole … although I suppose we could say it commemorates the season of unregulated and out of control gun violence. A few years ago, a young woman named Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed in Chicago; her friends began wearing orange, like hunters wear for safety, in her honor on her birthday in June. A couple of years ago, Bishops Against Gun Violence, an Episcopal group, became a co-sponsor of Wear Orange Day and some of us clergy here in Ohio decided to make and wear orange stoles on the following Sunday. Our decision got press notice and spread to clergy of several denominations all over the country.  Authority. The authority of Jesus Christ is what Paul writes about in the letter to the Philippians, in which he quotes a liturgical hymn sung in the early Christian communities:

Authority. The authority of Jesus Christ is what Paul writes about in the letter to the Philippians, in which he quotes a liturgical hymn sung in the early Christian communities: Have you ever had a friend try to tell you about going to see a stand-up comedian’s show? When I lived in Las Vegas, this happened fairly often in my workplace. Someone would go to see the late Robin Williams, or Jon Stewart (before he took over the Daily Show), or any of several who made regular appearances on the Strip, and then on Monday morning over coffee they would try to tell us how funny the show was.

Have you ever had a friend try to tell you about going to see a stand-up comedian’s show? When I lived in Las Vegas, this happened fairly often in my workplace. Someone would go to see the late Robin Williams, or Jon Stewart (before he took over the Daily Show), or any of several who made regular appearances on the Strip, and then on Monday morning over coffee they would try to tell us how funny the show was.