====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Seventh Sunday after Pentecost, July 23, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are from Proper 11A (Track 1) of the Revised Common Lectionary: Genesis 28:10-19a; Wisdom of Solomon 12:13,16-19; Romans 8:12-25; and St. Matthew 13:24-30,36-43. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Again, this week, we have another familiar parable in our Gospel lesson, the story of the wheat and the weeds. I will come back to it. But first, I’d like to tell you about my older brother who died 24 years ago.

Again, this week, we have another familiar parable in our Gospel lesson, the story of the wheat and the weeds. I will come back to it. But first, I’d like to tell you about my older brother who died 24 years ago.

Richard York Funston was born on July 27, 1943; this coming Thursday, he would have been 74 years old. Rick was a very, very smart man; I would even describe him as brilliant. He had a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Texas, a master’s in the same field from UCLA, and a PhD in political science specializing in constitutional law also from UCLA. He published five books on constitutional law and taught the subject in five universities, ending up as chair of the political science department and vice-president for academic affairs at San Diego State University. Had he lived, I’ve no doubt he would have been president of a major university.

But he did not live beyond his fiftieth birthday; in fact, he didn’t even get to that milestone. In October of 1992 he exhibited the first symptoms of some sort of brain dysfunction and was diagnosed as having suffered a stroke; three months later that diagnosis was proved wrong. He, in fact, was suffering from primary site brain cancer, glioblastoma multiforme, the same disease with which Senator John McCain has recently been diagnosed.

When Rick was diagnosed, I did some research into the disease and learned that, at that time, it was (and still is) considered incurable and invariable fatal. In 1993, 50% of patients died within six months of diagnosis; almost 100% percent, within two years. I’ve learned from the recent news about Senator McCain that medical science has extended the median survival to 18 months, but that outside life expectancy is still only about three years after diagnosis. Rick died on Father’s Day, June 21, 1993, less than five months after his accurate diagnosis. I spent the week before his death at his bedside.

So, I know all too well what John McCain and his family are facing and what they will be going through, and my heart goes out to them; they will daily be in my prayers. I would not wish what they are going through on anyone.

It’s because of Rick’s influence that I am the political junky that I am. He loved politics and we often discussed and debated the issues and races of the day. I have often wondered what he would make of 21st Century America and our current political climate. One of the things he taught me was to eschew what we have come to call “bubbles,” the self-insulating and self-reinforcing political and social circles in which we hear only those views that accord with our own and acknowledge only those facts which support our beliefs. So I read news reported by a variety of journals and read opinions and editorials written from a variety of points of view. I follow blogs and news-feeds from the Right, from the Center, and from the Left. And that is why I know that some self-identified “conservative Christians” have written that Senator McCain’s brain cancer is “godly justice” and that “God is punishing him” for his political views. (See Alexander Nazaryan, Newsweek, 7/20/2017.)

That is pure, unadulterated . . . nonsense! It’s that sort of offensive rhetoric by self-proclaimed “conservative Christians” that turns people off (and against) religion. What sort of person actually thinks and teaches others that God works that way? A god who did would not be a god to worship; such a god would be worthy only of contempt. Such a god would be one to follow; such god would be one to be fought. If I had even the slightest scintilla of a belief that that’s the way God operated, I’d not only not be a religious person, I’d be an anti-religious crusader. I am sick to death of the twisted, anti-human, distorted muck some people pass off as the Christian faith.

Which brings me back to Jesus and the parable in this morning’s Gospel text.

It is believed by many scholars that, in the parable of the wheat and the weeds, the weeds in question are darnel, a type of grass sometimes called “poisonous darnel.” The darnel itself is not poisonous, but it harbors a destructive and deadly fungus called “ergot.” If the infected darnel is harvested along with the wheat or rye, the ergot gets into the good grain and any flour or meal made from it, and the result can be fatal.

The scientific name for darnel is lolium temulentus, the second word being Latin for “drunk.” The French name for darnel is ivraie from the Latin ebriacus meaning “intoxicated.” Both names refer to the drunken, potential deadly nausea caused by eating the infected plant. Ergotism, as the symptoms of eating the fungus are called, is characterized headaches and nausea, convulsions and painful seizures and spasms, hallucinations and psychosis, and tingling and burning in the extremities, sometimes called “St. Anthony’s Fire.” (Wikipedia) Interestingly, these can also be the symptoms of glioblastoma.

Darnel is common throughout the Middle East and infestations of grain fields are a constant danger. So Jesus’ parable would have struck home forcefully with his original hearers; they knew well what might happen to someone who ate that fungus-infected grain. Later, Jesus explained the allegorical meaning of the parable to the Twelve, “the field is the world, and the good seed are the children of the kingdom; the weeds are the children of the evil one.” (Mt 13:38)

In his commentary on this story, scholar Eugene Boring suggests that “we can surely see, shimmering behind [this parable], the experience of Matthew’s church – and ours, too.” He goes on to write:

It chronically comes as a shock to find that the world, that the family into which we are born, that even the church is not an entirely trustworthy place. The world has places of wonder, but alleys of cruelty, too. Families cause deep pain as well as great joy. The church can be inspiringly courageous one moment and petty and faithless the next. Good mixes in with bad. “Where did these weeds come from?” is a perennial human cry. (Commentary on Matthew, The New Interpreters Bible: Volume VIII, Abingdon Press, Nashville:1995, pg 311)

Where did these people, these self-proclaimed “conservative Christians,” these poisonous weeds who cancerously distort the Gospel, blaming a devastating disease on some warped notion of “godly justice” come from?

Part of me, the part that still remembers my brother’s suffering, the part of me that sat by his death bed, would like to go root them out, pull them up root, stem, and head like the bad weeds they are, simply exterminate them. But, of course, the other part of me pays heed to the rest of the parable, to the master’s order to his servants to leave the darnels be until the harvest. This is, writes Boring, “a realistic reminder that the servants [which is to say, you and me] do not finally have the ability to get rid of the weeds and that sometimes attempts to pluck up weeds cause more harm than good.” (Ibid.)

Our gradual this morning is not taken from the Book of Psalms, as it usually is. Instead, we have a reminder from the deuterocanonical book entitled “The Wisdom of Solomon” that God, the source of righteousness, does not judge unjustly, that instead God judges with mildness and governs with forbearance. “Through such works,” we say to God as we recite the text, “you have taught your people that the righteous must be kind, and you have filled your children with good hope, because you give repentance for sins.” (Wis 12:19)

Paul writes in the same spirit in this morning’s epistle lesson. Echoing the parable’s message that the world is “not an entirely trustworthy place,” he writes, “The creation [is] subjected to futility.” (Rom 8:20) But we know that creation, and we ourselves, will one day be freed of that futility:

We know [writes Paul] that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience. (vv 23-25)

We could hope that our brothers and sisters, those so-called “conservative Christians,” could hear and learn that message. We could hope that they would stop broadcasting the perverse notion that God causes brain cancer, or earthquakes, or hurricanes, or floods, or whatever as punishment for human failings. We could hope that they would recognize what the great theologian Karl Barth stated so simply, that “God is either known by grace or he is not known at all.” (Church Dogmatics, II/1, 27)

We live in an imperfect world and we belong to an imperfect church, and there is very little we can do to change either of those facts; as much as we might wish to rip out and do away with those who distort the Christian message, the poisonous darnels among us, that isn’t our job. “We are given the task of living as faithfully and as obediently as possible, confident that the harvest is sure.” (Boring, op cit) We are to “wait for it with patience.”

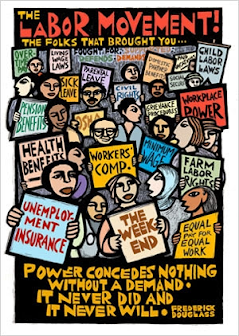

But not with passivity! The master’s prohibiting the servants from weeding the field “is not a divine command to ignore injustice in the world, violence in society, or wrong in the church.” (Ibid.) No! We must stand in witness not only against “the world, the flesh, and the devil,” but also against other self-identified “Christians” who pervert the Gospel. Whenever we hear or witness such nonsense as suggestions that Senator McCain’s brain cancer is “godly justice,” we must answer clearly that it is not! We must have the courage of our Christian convictions and proclaim the truth of our faith in the face of such distortion. What we hope these so-called “conservative Christians” hear and recognize and learn, we must say and demonstrate and teach.

In this respect, last week’s opening prayer bears repeating: When we are faced with such twisted falsehood and misrepresentation, O Lord, “grant that [we] may know and understand what things [we] ought to do, and also may have grace and power faithfully to accomplish them. Amen.” (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, Collect for Proper 10, page 231)

(Note: The illustration is a representation of glioblastoma cancer cells from Glioblastoma multiforme – stereotaxic radiotherapy brings promising results? by Aleksandra Jarocka, MD, and Anna Brzozowska, PhD.)

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Lenten Journal, Day 24

Lenten Journal, Day 24 Lenten Journal, Day 19

Lenten Journal, Day 19 Lenten Journal, Day 12

Lenten Journal, Day 12 On the third day there was a wedding in Cana of Galilee, and the mother of Jesus was there. Jesus and his disciples had also been invited to the wedding. – John 2:1-2

On the third day there was a wedding in Cana of Galilee, and the mother of Jesus was there. Jesus and his disciples had also been invited to the wedding. – John 2:1-2

A couple of months ago, I was part of a conversation among several parishioners about the set-up for our celebrations of the Nativity. We looking at our plans for Christmas services, and a member of our altar guild exclaimed, “That’s the problem! Things are always changing around here!”

A couple of months ago, I was part of a conversation among several parishioners about the set-up for our celebrations of the Nativity. We looking at our plans for Christmas services, and a member of our altar guild exclaimed, “That’s the problem! Things are always changing around here!” Recovery. It’s what they call the process that comes after surgery. A physician cuts you open, spends a few minutes or hours doing whatever needs to be done, sews (or staples or glues) you up, and they wheel you out of the surgical theater and into the recovery room. Recovery has started, but when you leave the recovery room it isn’t over. It goes on and on for days, weeks, even months.

Recovery. It’s what they call the process that comes after surgery. A physician cuts you open, spends a few minutes or hours doing whatever needs to be done, sews (or staples or glues) you up, and they wheel you out of the surgical theater and into the recovery room. Recovery has started, but when you leave the recovery room it isn’t over. It goes on and on for days, weeks, even months. When I told friends, colleagues, and parishioners I was contemplating a total knee replacement, the singular piece of consistent advice was, “Do the exercises! Keep up with the therapy!” The surgeon who was to do the deed gave me a booklet full of pre-operative exercises to do at least twice each day; that seemed doable and it was – twice a day for six weeks before surgery.

When I told friends, colleagues, and parishioners I was contemplating a total knee replacement, the singular piece of consistent advice was, “Do the exercises! Keep up with the therapy!” The surgeon who was to do the deed gave me a booklet full of pre-operative exercises to do at least twice each day; that seemed doable and it was – twice a day for six weeks before surgery. What do orange-haired casino owners, former First Ladies, Muslim refugee children, police officers, unborn babies, doctors and nurses who perform abortions, progressive hipsters, conservative Republicans, prosperity-gospel televangelists, members of Congress, transgender former athletes, Confederate-flag-waving white nationalists, Black Lives Matter activists, middle-of-the-road Democrats, and aging clergy all have in common?

What do orange-haired casino owners, former First Ladies, Muslim refugee children, police officers, unborn babies, doctors and nurses who perform abortions, progressive hipsters, conservative Republicans, prosperity-gospel televangelists, members of Congress, transgender former athletes, Confederate-flag-waving white nationalists, Black Lives Matter activists, middle-of-the-road Democrats, and aging clergy all have in common?  Again, this week, we have another familiar parable in our Gospel lesson, the story of the wheat and the weeds. I will come back to it. But first, I’d like to tell you about my older brother who died 24 years ago.

Again, this week, we have another familiar parable in our Gospel lesson, the story of the wheat and the weeds. I will come back to it. But first, I’d like to tell you about my older brother who died 24 years ago.