There’s something about old monastic ruins and the tumble-down wrecks of old stone churches that appeals to me. I’m not sure why, but there is. When we visited Ireland in 2005 and again in 2007, I dragged my poor wife Evelyn to and through so many religious ruins that I’m sure she’s seen more than enough of them.

But not me!

Today I drove from Clovenfords to Melrose, visited Melrose Abbey and Harmony Gardens, then drove on to Jedburgh and visited Jedburgh Abbey. After that, I turned toward Holy Island (Lindisfarne) and wandered through the Scottish Borders and Northumberland countrysides taking very small country roads across northeaster England. And when I got to the Holy Island, I made a preliminary visit to Lindisfarne Priory to which I will return tomorrow. Three monastic ruins in one day!

It was a very full day with lots to consider, lots to think about, and lots to relate. So let us return to Clovensford Country Hotel for the moment and consider the “full Scottish breakfast.” The full Irish, it ain’t! At least as served at Clovensford. Don’t get me wrong; it was a lovely breakfast, but it wasn’t what I was expecting.

It was a very full day with lots to consider, lots to think about, and lots to relate. So let us return to Clovensford Country Hotel for the moment and consider the “full Scottish breakfast.” The full Irish, it ain’t! At least as served at Clovensford. Don’t get me wrong; it was a lovely breakfast, but it wasn’t what I was expecting.

In the breakfast room (the same restaurant where I’d had dinner the night before), the bar was set with cereals (for types in individual boxes), a basket of various sorts of croissants, muffins, and breakfast rolls, some packets of marmalade and jam, and four pitchers – one of milk, three of juice (orange, grapefruit, and cranberry). I was greeted by the same young woman who had served dinner and told to take any set table, which I did after selecting a cereal (Kellogg’s Fruit & Fibre), a croissant, and a packet of marmalade, and pouring a glass of orange juice.

She then asked if I wanted tea or coffee… Coffee, of course! …and handed me the breakfast menu. There were four options the first of which was the “full Scottish breakfast.” I don’t remember now what the others were, though I do recall that one was vegetarian and one involved smoked salmon. I ordered the “full Scottish” and requested my egg over-medium, which she confirmed. When it came, it was sunny-side up. No problem.

The rest of the plate consisted of grilled mushrooms (some exotic sort with long stems), two rashers of English (or, I suppose, Scottish) bacon which is much meatier than American bacon (more along the lines of so-called Canadian bacon), a sausage link, a grilled tomato half, what looked for all the world like one of those triangular hash-brown things you get at McDonald’s, about a half-cup of baked beans (exactly like Campbell’s pork-and-beans), and a round patty of what was billed as haggis, obviously cut from a canned product. She also delivered a rack of eight triangular pieces of toasted white bread (it could have been Wonder Bread).

The full Irish is described elsewhere on this blog and, while similar, the Scottish version just seemed skimpy … only one small egg, one banger, and haggis is no substitute for black pudding!

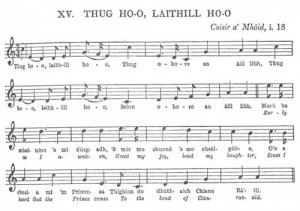

As I drove off after the breakfast, feeling somewhat dissatisfied with the whole thing, I recalled a short hymn from the Pentecost hymns section of Dantá Dé which is simply entitled Hymn of Mael-Isu, the author of the lyrics being identified as Mael-Ísú Ó Brolchám, an 11th Century poet one assumes since the hymn is dated 1038. (Textual notes indicate that Ní Ógáin found it in a musical manuscript from 1756 by “G. Flood, Dr. Mus.”) The Irish of the hymn is

An Spioraid Naomh, umainn, ionainn agus againn,

An Spioraid Naomh chugainn go dtige, a Chriost, go h-obann.An Spioraid Naomh d’áitreabh ár gcuirp is ár n-anma,

Dár gcúmhdach go lághach ár ghuaisibh ‘s ar ghalraibh.Ar bheamhnaibh, ar pheacaidh’, ar ífrionn ‘s ar fhíor-loit,

A Íosa, go naomhaighe, go saoruigh’ inn Do Spioraid.

The English translation by Ní Ógáin is

May the Holy Spirit be about us, in us, and with us,

May the Holy Spirit, O Christ, come to us speedily.May the Holy Spirit dwell in our bodies and our souls,

May He protect us generously against perils, against diseases;Against demons, against sins, against hell, against real woundings;

O Jesu, may Thy Spirit hallow us, deliver us.

I don’t know why this particular bit of the hymnal came to mind, this sort of mini-lorica*, but it did. As I recited it while driving, as I thought on the prayer in this hymn, I knew that my breakfast, although it hadn’t lived up to my expectations (which were unrealistic – who am I to say what “the full Scottish” ought to be?), was more than enough to get me on my way for the day. It was plenty, more than enough really. What’s more important than breakfast is the presence and protection of the Lord, and the hymn reminded and reassured me of that. So, filled with good Scottish nourishment and assured of God’s blessing, I had a lovely day of visiting monastic ruins and tumble-down wrecks of old churches!

I’ll have more to say in other posts today about the abbeys, the gardens, the countryside, and Holy Island, and there are photos of all that on the Flickr page.

(* lorica – an Irish verse-form prayer for God’s protection. According to Wikipedia, “In the Christian monastic tradition, a lorica is a prayer recited for protection. The Latin word lorica originally meant ‘armor’ or ‘breastplate.’ Both meanings come together in the practice of placing verbal inscriptions on the shields or armorial trappings of knights, who might recite them before going into battle.” Perhaps the most famous lorica is St. Patrick’s Breastplate.)

Last evening as I walked the dog after sunset, the sky still a fairly bright blue with plenty of light to see, I looked into the darkness of the woods behind our house and saw that the fireflies were beginning to flash their mating signals. I realized that I’m leaving Ohio at one of my favorite times of the year – firefly time! I love fireflies!

Last evening as I walked the dog after sunset, the sky still a fairly bright blue with plenty of light to see, I looked into the darkness of the woods behind our house and saw that the fireflies were beginning to flash their mating signals. I realized that I’m leaving Ohio at one of my favorite times of the year – firefly time! I love fireflies!