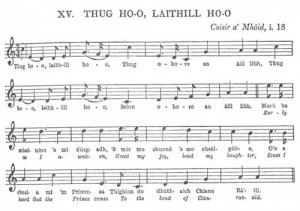

Between the steps outlined in my last two posts, there is the matter of music. The metre, the accents, the stressed syllables … all that has to be considered. Hymn metres are often described numerically by the number of syllables in each line. For example, the great Lutheran hymn A Mighty Fortess Is Our God is metrically described “87 87 87 66 7” – this means that in each nine-phrase stanza, the first line has eight syllables, the second seven, the third eight, and so on.

I look over the music in Dánta Dé and determine, using this syllable-count scheme, what the metre of the translation should be, how the music fits the Irish lyrics and how best an English re-working might fit. And then, working from the literal translations of ní Ógáin and my own literal translation, I begin crafting a metrical paraphrase.

One of my favorite pieces in the hymnal is entitled The Heavenly Habitation, written by Donnchad Mór Ó Dálaigh in the 13th Century. Here it is in three versions – the original archaic Gaeilge, ní Ógáin’s translation, and my final metrical, rhyming paraphrase.

The original Irish Gaelic:

Áluinn Dún Mhic Mhuire,

An Dún is gluine blat;

Aoibhneas ann agus ceo,

Ní fhaicthear brón go brat.Ní fhaicthear ann cean crom,

Tuirse trom ann nó cás,

Ní fhaicthear cúis no coir,

Ar aon neach ann go brat.Do chídhtear ann do shíor,

Aoibhneas Ríogh na ngrás;

Do chídhtear sin san Dún

Soillse nach múcann smal.An Spioraid Naomh go taithneamhac

Mar gaethibh siúbhlac’ gréine,

Is É ag scaoileadh go ceathannach

[Glé-] grása Ríogh na Féile.San mbrúgh suaithneach solus-bhlát,

– Óir ‘s ionann lá is oidhche –

Ó chorraibh ‘n bhrógha bháin-ghil

Tig deallradh lán do’n aoibhneas.Tá mile ógh is máirtireach

Fuair san tsaoghal gach dochar,

Lán dá n-aoibhneas taithniomhach

Ann go sámh glan socair.Gorta is iota is ocras

‘S gach uile galar claoidhte,

Deoch as tobar na trócaire

D’fhóirfeadh iad sin choidhche.Iompuighmíd ar ár n-ais arís,

Go bhfeicmid Ri na ngrása,

Is iarrmaoid ar ár nglúine

Ár leigean ‘san Dún is áilne.

Úna ní Ógáin’s direct translation:

Beauteous the Dún of the Son of Mary,

The Dún of purest bloom;

Delight is there and music,

And sorrow ne’er shall be seen there.Ne’er shall be seen there a head bowed down,

Heavy weariness nor care;

Never sorrow nor crime

On anyone there for ever.For ever is seen there

The loveliness of the King of the graces;

This is seen in that Dún,

Light that no cloud shall quench.The Holy Spirit radiantly

Like moving beams of the sun,

And He shedding in showers

The graces of the King of generosity.In the Fortress colour-full, light-blossoming,

– For there day and night are the same , –

From the pinnacles of the fair bright Fortress

Comes radiance full of delight.A thousand virgins and martyrs

Who received in the world all hardships,

Filled with joyful delight

Are there, peaceful, pure, safe.Famine and thirst and hunger,

And every wearing disease, –

A drink from the Well of Mercy

Would relieve them for ever.We will return back again

That we may see the King of the graces,

And beseech him on our knees

To take us into the Dwelling most beauteous

My work based on this hymn:

How wondrous bright the glorious dún

of Jesus Christ our King;

Delight is there for ev’ryone,

and there the martyrs sing.No head is bowed with sorrow there,

no heavy weariness known;

No crime, no cloud, no toilsome care,

bedims that heav’nly home.The beauteous mansions of God’s Son

all sound with music bright;

The radiant Spirit, like the sun,

Fills them with glorious light.The graces of the King are spread

and purest loveliness blooms

on all the holy, faithful dead

who now live in God’s rooms.The many virgins, martyrs, saints

who hardship all endured

are filled with joy, delight, and grace;

blest, peaceful, and secure.From famine, suff’ring, thirst, disease,

the Well of Mercy has giv’n

release and comfort to all these

who now dwell in God’s heav’n.That heav’nly habitation we

all live in hope to share;

The King of all the graces we

beseech to take us there.Upon our knees, the King we pray

will there make welcome our souls,

where ev’ry night is bright as day,

and ev’ry life made whole.How wondrous bright, the glorious dún

of Jesus Christ our King;

Delight is there for ev’ryone,

and there we all shall sing.There ev’ry soul is pure and bright,

and ev’ry loveliness known;

There joy, and peace, and pure delight

bless our eternal home.

There are about eighty ancient Gaelic hymns in the hymnal (there are also Gaelic translations of familiar hymns, especially Christmas carols, which I will be ignoring). My sabbatical project will be to work on these metrical, rhyming English paraphrases for as many as I can complete during my time on leave.