This is a picture of stone found at (and now on exhibit at) the monastic ruins of Clonmacnoise in County Offaly, Éire. In the center of the cross is a design known as a “Celtic triskele.” This symbol appears in many places and periods, it is especially characteristic of the Celtic art of the continental La Tène culture of the European Iron Age (a Celtic society which predates Celtic Ireland).

Inscribed Stone with Center Triskele from Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, Éire

This symbol was often used in the artwork of the early Irish Christians as a symbol of the Holy Trinity. Often seen in Irish art is a triskele of three conjoined spirals. Although it is considered a Celtic symbol, this type of triskele is in fact pre-Celtic; the triple spiral motif is a Neolithic symbol in Western Europe. It is found, for example, carved into the rock of a stone lozenge near the main entrance of the prehistoric Newgrange burial monument in County Meath, Ireland. Newgrange which was built around 3200 BCE, well before the arrival of the Celts in Ireland.

This is another example of an inscribed cross with a triskele in the center, also from Conmacnoise:

Inscribed Stone with Center Triskele from Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, Éire

Another familiar Celtic symbol of the Trinity is the triquetra or “Celtic Trinity knot”. One finds items of jewelry bearing this symbol for sale in all the tourist trinket shops in this country, and variations of both the triskele and the triquetra grace the Book of Kells and other Irish illuminated manuscripts.

A Triquetra Pendant

Celtic Christianity is exuberantly Trinitarian, as these designs suggest. However, getting a real “handle” on a settled Celtic theology of the Trinity is quite difficult. One of the earliest Celtic theologians was Pelagius, a 4th Century British contemporary of St. Augustine of Hippo. Unfortunately, we have few, if any, original texts by Pelagius, only Augustine’s assertions about what Pelagius taught and a few quotations from Pelagius in other sources. In any event, the heresy which now bears Pelagius’ name (whether he actually taught it or not) was quite at odds with Augustine’s own teaching of “original sin”. According to Augustine, Pelagius taught that human nature is basically good and refuted the concept of original sin; people, said Pelagius (according to Augustine), have the ability to fulfill the commands of God by exercising the freedom of human will apart from the grace of God. This teaching was condemned by the church and early Celtic theology is remembered today mostly only as the source of this heresy called “Pelagianism”. (Whether Pelagius or the Celtic church were truly Pelagian or not, it has been suggested that Pelagianism is “the besetting sin of British theology.” “British theology,” theologian Karl Barth once remarked, “is incurably Pelagian.”)

In any event, Pelagius did produce a treatise on the Trinity entitled On Faith In The Trinity: Three Books of which one scholar has said:

By the time of Pelagius then, there were two accepted doctrines which had been hammerred out against the heretics and laid down by the Church in black and white, those of the Incarnation and the Trinity. No one could, or did, accuse Pelagius of denying these two fundamental doctrines; on the contrary, his teachings show that he lost no opportunity of attacking any who had done so, and not even Augustine claimed that his christology was other than orthodox. (Pelagius: Life and Letters, B.R. Rees, 1988, pp. 24-25)

A second influential Celtic theologian was Johannes Scotus Eriugena in the 9th Century; his name means “John, the Irishman, born in Ireland.” He has been called the Celtic world’s most significant philosophical thinker; Bertrand Russell called him “the most astonishing figure of the early Medieval period.” Unfortunately, like Pelagius before him, he was condemned as a heretic. Perhaps ahead of this time, he constantly wrote of God as “nothing”; for example, Eriugena called God nihil per excellentiam (“nothing on account of excellence”) and nihil per infinitatem (“nothing on account of infinity”). By using the term “nothing” (more accuretly, “no thing”), Eriugena seems to have meant that God transcends all created being. He also insisted on describing God as “nature which creates”; this eventually got him condemned as a pantheist and a heretic, and his books were burned in the 13th Century.

Nonetheless, we do have quotations from Eriugena which show that like Pelagius, he was thoroughly a Trinitarian:

The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit consume our sins together, and by theosis convert us, as though we were a holocaust, into their unity.

and

From the deformity of our imperfection after the fall of the first human being, the Holy Trinity brings us up to the perfect human being and trains us for the fullness of Christ’s time.

From the known writings of these two important Celtic theologians, then, we know that early Celtic Christians honored the Triune God. There is a pious legend (probably dating from no earlier than the 1700s) that St. Patrick brought the doctrine of the Trinity to Ireland and explained it to his converts using the shamrock as an illustration. When I was hiking with him through the bogs of County Galway a few weeks ago, historian and archeologist Michael Gibbons scoffed at that notion. The shamrock is relatively uncommon, even though in the 19th Century it became a symbol of rebellion against the English. Gibbons suggested that if Patrick used any plant, it was probably the trifoliate bogbean, which grows in profusion.

The Celts were probably predisposed to easily accept the doctrine of the Trinity. Irish (and other Celtic) folk lore is replete with proverbs (seanfhocail) in the form of triadic sayings. Here are a few:

There are three kingdoms of the happy: the world’s good word, a cheerful conscience, and firm hope of the life to come.

Three leaderships of the happy: being good in service, good in disposition, and good in secrecy; and these are found united only in those with a noble heart.

In three things a person may be as the Divine: justice , knowledge , and mercy.

Three things lovable in a person: tranquillity, wisdom, and kindness.

Three things excellent in a person: diligence, sincerity, and humility.

Three things which show a true human: a silent mouth, an incurious eye, and a fearless face.

[There are many websites dedicated to these triads; one of the best is Trecheng Breth Féne – The Triads of Ireland.]

Other evidence of a solid Trinitarian theology in Celtic Christianity includes the hymn bearing Patrick’s name, St. Patrick’s Breastplate. This hymn is a long invocation of the Trinity in the poetic form known as a lorica, a Druidic incantation for protection on a journey. It is best known in the metrical translation by Cecil Frances Alexander found in many hymnals (including The Hymnal 1982 of the Episcopal Church). The first lines in her translation are:

I bind unto myself today

the strong Name of the Trinity,

by invocation of the same,

the Three in One, and One in Three.

This hymn also appears in Dánta Dé, where one finds these lines translated by Douglas Hyde in this way:

I arise to-day

In strong power, strong prayer to the Trinity,

And in powerful faith in the Three,

In humble pure confession of the Unity,

High Creator of all elements.

In Celtic poetry, therefore, is a strong sense of the power of the Triune God, but there is also an amazing sense of the intimacy of the Trinity. Belief in the Trinity in Celtic thought is closely bound with a sense of the closeness, the friendship of God. In Dánta Dé is a hymn described as a “folk song for the morning” in which God is addressed as a Rí na gcarad. I translate this as “the King of friends” and Dr. Hyde has rendered it “the King of friendship.” One finds a similar sense of God as companion in a morning invocation from the Carmina Gadelica, a collection of folk charms, songs, and prayers collected by Alexander Carmichael in Scotland at the end of the 19th Century. In fact, this is the piece with which Carmichael begins his collection:

I am bending my knee

In the eye of the Father who created me,

In the eye of the Son who purchased me,

In the eye of the Spirit who cleansed me,

In friendship and affection.

This sense of intimacy in and with the Holy Trinity is similar to the theology and practices of Eastern Orthodoxy with which the Celtic Christians were very familiar. When St. Augustine of Canterbury arrived in Britain at the end of the 6th Century, his missionaries found that Christianity was already there and had been since probably the late 2nd or early 3rd Century! (The martyrdom of St. Alban, first martyr of Britain, has been dated by some scholars to as early at 209; St. Patrick’s missionary activity in Ireland was accomplished in the middle of the 5th Century.)

The Roman missionaries found that the Celts used a very early system to determine the celebration of Easter, a system they had learned centuries before from Eastern Christians. They also found the Celts using an order of service for baptism similar to the Eastern Orthodox service. Furthermore, although the Celtic Christians had celibate monks and nuns, they had married priests in keeping with ancient tradition which still exists in Orthodoxy and which was reclaimed in the West by the reformed churches.

So it is not surprising that we find in Celtic Christian belief and practice a sense of the Trinity not dissimilar to that of the Eastern church. Ian Bradley in The Celtic Way writes:

The Celts saw the Trinity as a family … For them it showed the love that lay at the very heart of the Godhead and the sanctity of family and community ties. Each social unit, be it family, clan or tribe, was seen as an icon of the Trinity, just as the hearthstone in each home was seen as an altar. The intertwining ribbons of the Celtic knot represented in simple and graphic terms the doctrine of perichoresis – the mutual interpenetration of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. (The Celtic Way, 2007, p. 44)

Perichoresis is term from Eastern Orthodox theology which describes our understanding that in all actions of God each of the Persons of the Holy Trinity takes part. Anglican theologican Alister McGrath writes that it “allows the individuality of the persons to be maintained, while insisting that each person shares in the life of the other two.” (Christian Theology: An Introduction, 3rd ed., 2001, p. 325)

The word itself is a compound word with two Greek roots: peri, which means “around”, and choreia, which means “dance”. Thus, it describes the Holy Trinity as eternally dancing: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit moving and flowing together in creation, in redemption, in sanctification, and drawing life from one another in a dance of perfect love. John of Damascus, who was influential in developing the doctrine of the perichoresis, described it as a “cleaving together”. It is an image of intimate friendship.

In Dánta Dé there are two short morning hymns with which I’ve been particularly taken. The first is the one to which I alluded earlier naming God as the “King of friendship”. Ms. ní Ógáin attributes the English translation in the hymnal’s appendix to Dr. Hyde:

O King of friendship, our Saviour’s Father art Thou;

O keep me erect, until the evening shall cool my brow.

O teach and control, lest I unto any sin should bow,

Save Thou my soul from the foe who follows me now.

O King of the world, Who lightest the sun’s bright ray,

Who movest the rains that ripen the fruit on the spray;

I look unto Thee, my transgressions before Thee I lay,

O keep me from falling deeper and deeper away.

The second is entitled An Réalt (“The Star”) and is described as an “old song of Ireland”. This is my translation of the Irish:

O Jesus, be in my very heart’s memory every hour,

O Jesus, be in my very heart’s quick repentance,

O Jesus, be in my very heart’s unfailing fellowship,

O Jesus, true God, do not cut yourself off from me.

Without Jesus my thoughts are not pleasing to myself,

Without Jesus neither my writing nor the words of my mouth;

Without Jesus my actions in life are not good

O Jesus, true God, be before me and behind me.

Jesus is my very King, my friend, and my love;

Jesus is my refuge from sin and from death;

Jesus is my joy, my constant mirror,

O Jesus, true God, do not part from me forever

Jesus, always be in my heart and on my lips,

Jesus, always be first in my understanding,

Jesus, always be in my memory like readings,

O Jesus, true God, do not leave me by myself.

Inspired by these two hymns and their melodies, I’ve written new lyrics picking up some images from the originals, together with the metaphor of the dance, and set them to a combined arrangement of the music. This is my poetry and below it a link to a five-minute MP3 of the arrangement. The music is synthesized piano and a synthesized SATB choir. I have neither a piano, nor a choir, nor recording facilities in the 300-year-old farm house cottage in which I am on retreat, so a computer synthesis will have to do. Unfortunately, the synthetic sounds are not as good as I would like and the playback is a bit uneven. Still, it gives an idea of the sort of thing I’ve been working on during this sabbatical. I look forward to polishing this up and working with a real choir and accompanist on this piece.

Be in our world, O Father, our refuge and our king.

Be in our world, O Father, forever sheltering.

Before us and behind, from sin and death our souls protecting.

O Father, the source of grace, our refuge and our king.

O author of friendship, the One, Holy Trinity,

In the dance of creation you formed us for community.

With your love lead and guide us, as you invite us to the dance ev’ry day.

We follow your lead for we trust in your saving way.

Be in our hearts, O Jesus, with your unfailing power.

Be in our hearts, O Jesus; be with us ev’ry hour.

Do not leave us alone, our constant friend and our companion,

O Jesus, the Son of love, with your unfailing power.

Be in our minds, O Spirit, and always in our praise.

Be in our minds, O Spirit, our actions and our ways.

Be first upon our lips, first in our thoughts and understanding.

O Spirit, our unity, always be in our praise.

O author of friendship, the One, Holy Trinity,

In the dance of creation you formed us for community.

With your love lead and guide us, as you invite us to the dance ev’ry day.

We follow your lead for we trust in your saving way.

O Trinity of friendship, always be in our lives;

O Trinity of friendship, surrounding us with light.

Community of love forever offering us welcome,

O Trinity, our Lord and God, always be in our lives.

O author of friendship, the One, Holy Trinity,

In the dance of creation you formed us for community.

With your love lead and guide us, as you invite us to the dance ev’ry day.

We follow your lead for we trust in your saving way.

O Father of grace, Son of love, Spirit of unity,

In the dance of salvation you show what you call us to be;

As we join in the fellowship of your dance, loving you as we ought,

O Trinity of friendship always be in our hearts.

O Trinity, our Lord and God, always be in our hearts.

Click on the title, Trinity of Friendship, to listen to the synthesize piano and choir.

I confess to a certain fondness for the Galatians. I’ve never been a really big fan of Paul the Apostle and I sometimes wistfully wonder how our Christian faith might have developed if he had not been its principal post-Ascension spokesperson. What if the Johanine community that produced the Gospel of John and the three letters that also bear his name had been more prominent? What if James and his insistence on works of mercy because “faith, if it has no works, is dead” (James 2:17) had been more influential than Paul’s assertion to the Romans that salvation is “by grace, it is no longer on the basis of works” (Romans 11:6)? Well, we’ll never know . . . but apparently the Galatians were listening to someone suggest an alternative to Paul’s understanding of the Christian gospel and, as a result, he wrote them this letter. Anybody that could so upset Paul that he would call them “you foolish Galatians” (Gal. 3:1) gets high marks in my book! That the Galatians were also Celts with whom I, as an Irish-American, share an ethnic heritage gives them additional credit.

I confess to a certain fondness for the Galatians. I’ve never been a really big fan of Paul the Apostle and I sometimes wistfully wonder how our Christian faith might have developed if he had not been its principal post-Ascension spokesperson. What if the Johanine community that produced the Gospel of John and the three letters that also bear his name had been more prominent? What if James and his insistence on works of mercy because “faith, if it has no works, is dead” (James 2:17) had been more influential than Paul’s assertion to the Romans that salvation is “by grace, it is no longer on the basis of works” (Romans 11:6)? Well, we’ll never know . . . but apparently the Galatians were listening to someone suggest an alternative to Paul’s understanding of the Christian gospel and, as a result, he wrote them this letter. Anybody that could so upset Paul that he would call them “you foolish Galatians” (Gal. 3:1) gets high marks in my book! That the Galatians were also Celts with whom I, as an Irish-American, share an ethnic heritage gives them additional credit. On the second day of Christmas the church remembers a murder, the martyrdom of Stephen, and our Daily Office lectionary won’t let us forget it. Often the readings of the Daily Office seem to have nothing to do with the season and they seldom are tied to a saint’s commemoration, but today the morning and evening readings tell the whole story in gruesome detail.

On the second day of Christmas the church remembers a murder, the martyrdom of Stephen, and our Daily Office lectionary won’t let us forget it. Often the readings of the Daily Office seem to have nothing to do with the season and they seldom are tied to a saint’s commemoration, but today the morning and evening readings tell the whole story in gruesome detail. Perhaps among the most familiar words from St. John’s apocalypse, “Blessed are they who are invited to the marriage feast of the Lamb.” They are used as a fraction anthem or invitation to communion in many churches. But in this brief passage from Revelation, the most powerful image for me today is the angel saying, “I am a fellow-servant with you and your brothers and sisters.”

Perhaps among the most familiar words from St. John’s apocalypse, “Blessed are they who are invited to the marriage feast of the Lamb.” They are used as a fraction anthem or invitation to communion in many churches. But in this brief passage from Revelation, the most powerful image for me today is the angel saying, “I am a fellow-servant with you and your brothers and sisters.” The collect for today from The Book of Common Prayer:

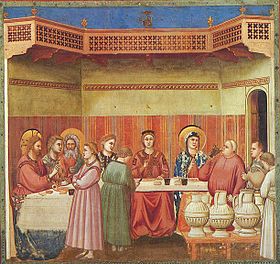

The collect for today from The Book of Common Prayer: A year ago I was in Ireland, camped out in a cottage outside of the village of Banagher, County Offaly, on sabbatical. As my study project, I was translating old Irish hymns into metrical, rhyming English such that they could be sung to the music of the original. The hymns were published in the early 20th Century in a collection titled Dánta Dé Idir Sean agus Nuadh compiled by Uná ní Ógáin. Dánta Dé includes a communion hymn which elaborates on John’s story of the wedding feast; it is entitled The Blessed Wedding at Cana and is attributed to Maighréad ní Annagáin. I found I could not directly translate the hymn, so instead I wrote a poem of my own. Reading this story today, I recall working on that piece and offer it again.

A year ago I was in Ireland, camped out in a cottage outside of the village of Banagher, County Offaly, on sabbatical. As my study project, I was translating old Irish hymns into metrical, rhyming English such that they could be sung to the music of the original. The hymns were published in the early 20th Century in a collection titled Dánta Dé Idir Sean agus Nuadh compiled by Uná ní Ógáin. Dánta Dé includes a communion hymn which elaborates on John’s story of the wedding feast; it is entitled The Blessed Wedding at Cana and is attributed to Maighréad ní Annagáin. I found I could not directly translate the hymn, so instead I wrote a poem of my own. Reading this story today, I recall working on that piece and offer it again. I’m not sure, but those may be my three favorite words in all of Paul’s writings: “You stupid Celts!” That’s what he’s saying here. The Galatians were Celts, distant cousins of the Irish, Welsh, Scots, and Bretons. They all had their origins in the Celtic homelands of the northwestern Alps and migrated to Asia Minor, the islands of Britain and Ireland, and other places. And here Paul calls the Celts of Asia Minor anoetos, a Greek word which means “lacking understanding” and is variously translated as foolish, thoughtless, senseless, or stupid. “You stupid Celts!” ~ It is generally believed that Paul is reacting against the Galatians acceptance of the suggestion of the “Judaizers” that they needed to be circumcised before they could really become Christians. But I wonder . . . . I’ve done a fair amount of study of Celtic spirituality, at least of the western (British Isles) sort; I spent a three-month sabbatical translating ancient Gaelic religious poetry. The western Celtic understanding of Christ’s work was rather different from the Pauline notion. Paul (especially as developed by Augustine but, I think pretty clearly, originally) saw Christ’s salvific work in terms of propitiation and justification: just a few more verses and he will insist to the Galatians “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law.” (v. 13) The Celts, on the other hand, thought in terms of Jesus completing the goodness of creation; they believed much like Origen did that human beings were not so much fallen or cursed by sin as immature and incomplete, striving not for redemption but for perfection. ~ Some of Origen’s views were eventually anathematized as heretical and, though he is viewed as a “Church Father”, he has not been sainted. Later Celtic theologians have suffered the same indignity. The Irishman Johannes Scotus Eriugena believed that all human beings reflect attributes of divinity and that all are capable of progressing toward perfection, a view that Paul would clearly have disputed; Eriugena’s theology was discredited as “Irish porridge” and “an invention of the devil.” The Culdee monk Pelagius (who was probably a Breton rather than Irish) taught that humans do not have inherent sinfulness, but rather have a natural sanctity and the moral capacity to choose to live a holy life; Pelagius, too, was condemned as a heretic. ~ I sometimes wonder if this pervasive western Celtic belief in the essential goodness of humankind and in the progressive divinization or completion of creation might have been shared by their eastern cousins in Galatia. If so, it might have been this which led them to be more accepting of the Judaizer’s suggestions; after all, if the Christian goal is divinization and if circumcision put the Chosen People closer to God, perhaps it ought to be considered. No wonder Paul, who didn’t believe human beings could do anything to contribute to their own sanctification, thought them stupid and foolish! How different might the Christian church today be if the views of the Galatians, Pelagius, Eriugena, and other Celts had prevailed? One will never know. ~ I do know this, however. Those Celtic views ought to be heard and considered. None of us fully knows the mind of God and the views and thoughts of all should be valued as we struggle together to understand. They may be my favorite words of Paul, but not because they are particularly beneficial; indeed, they are not. The church today would be much better off and a much more congenial society if no one ever said or wrote anything like, “You stupid Celts!”

I’m not sure, but those may be my three favorite words in all of Paul’s writings: “You stupid Celts!” That’s what he’s saying here. The Galatians were Celts, distant cousins of the Irish, Welsh, Scots, and Bretons. They all had their origins in the Celtic homelands of the northwestern Alps and migrated to Asia Minor, the islands of Britain and Ireland, and other places. And here Paul calls the Celts of Asia Minor anoetos, a Greek word which means “lacking understanding” and is variously translated as foolish, thoughtless, senseless, or stupid. “You stupid Celts!” ~ It is generally believed that Paul is reacting against the Galatians acceptance of the suggestion of the “Judaizers” that they needed to be circumcised before they could really become Christians. But I wonder . . . . I’ve done a fair amount of study of Celtic spirituality, at least of the western (British Isles) sort; I spent a three-month sabbatical translating ancient Gaelic religious poetry. The western Celtic understanding of Christ’s work was rather different from the Pauline notion. Paul (especially as developed by Augustine but, I think pretty clearly, originally) saw Christ’s salvific work in terms of propitiation and justification: just a few more verses and he will insist to the Galatians “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law.” (v. 13) The Celts, on the other hand, thought in terms of Jesus completing the goodness of creation; they believed much like Origen did that human beings were not so much fallen or cursed by sin as immature and incomplete, striving not for redemption but for perfection. ~ Some of Origen’s views were eventually anathematized as heretical and, though he is viewed as a “Church Father”, he has not been sainted. Later Celtic theologians have suffered the same indignity. The Irishman Johannes Scotus Eriugena believed that all human beings reflect attributes of divinity and that all are capable of progressing toward perfection, a view that Paul would clearly have disputed; Eriugena’s theology was discredited as “Irish porridge” and “an invention of the devil.” The Culdee monk Pelagius (who was probably a Breton rather than Irish) taught that humans do not have inherent sinfulness, but rather have a natural sanctity and the moral capacity to choose to live a holy life; Pelagius, too, was condemned as a heretic. ~ I sometimes wonder if this pervasive western Celtic belief in the essential goodness of humankind and in the progressive divinization or completion of creation might have been shared by their eastern cousins in Galatia. If so, it might have been this which led them to be more accepting of the Judaizer’s suggestions; after all, if the Christian goal is divinization and if circumcision put the Chosen People closer to God, perhaps it ought to be considered. No wonder Paul, who didn’t believe human beings could do anything to contribute to their own sanctification, thought them stupid and foolish! How different might the Christian church today be if the views of the Galatians, Pelagius, Eriugena, and other Celts had prevailed? One will never know. ~ I do know this, however. Those Celtic views ought to be heard and considered. None of us fully knows the mind of God and the views and thoughts of all should be valued as we struggle together to understand. They may be my favorite words of Paul, but not because they are particularly beneficial; indeed, they are not. The church today would be much better off and a much more congenial society if no one ever said or wrote anything like, “You stupid Celts!”