====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Sixteenth Sunday after Pentecost, September 4, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 18C of the Revised Common Lectionary: Deuteronomy 30:15-20; Psalm 1; Philemon 1-21; and St. Luke 14:25-33. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

“Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.”

“Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.”

Jesus just doesn’t make it easy, does he? He doesn’t make it easy to preach this Gospel of his; he doesn’t make it easy to life this life of his! He just doesn’t.

And then there’s Paul! Sending a slave back to his owner, a slave who apparently ran away and owes his owner something. And Paul doesn’t even say to the slave owner, “Set him free.” He sort of hints at it, I guess, but he doesn’t come right out and say it! He doesn’t make this any easier.

And, of course, there’s Moses: “I have set before you today life and prosperity, death and adversity.” One way or the other, black or white, yes or no, no grays, no (as my mother would have said) “ifs, ands, or buts,” no compromises, no negotiations. Take it or leave it. Decide.

They don’t make it easy.

So let’s just ignore them, OK. It’s Labor Day weekend, so let’s just not work that hard.

Labor Day, as you already know because you read the parish’s weekly email update on Friday, was created by Congress in 1894 as a “workingman’s holiday” on the first Monday of September and has remained so for 122 years. In 1909, the American Federation of Labor adopted a resolution calling on churches to observe “Labor Sunday” on the day before Labor Day, and nearly every denomination including our own did so. The prior year the Federal Council of Churches had adopted the “Social Creed of the Churches” which called for “equal rights and complete justice for all men in all stations of life,” a living wage, abatement of poverty, and numerous worker protections, including arbitration, shortened workdays, safer conditions, the abolition of child labor, regulation of women’s labor, and assistance to elderly and incapacitated workers. “Labor Sunday” fit right in with those lofty social goals.

Observance of Labor Sunday waned in the 1960s; today (to the best of my knowledge) it is an official observance only in the United Church of Christ. We, however, have paid homage to this heritage when we sang the hymn Divine Companion as our Sequence a few moments ago. It was written by Henry Van Dyke in 1909 as a “Hymn of Labor” and set to the American folk hymn melody Pleading Savior which dates from before the Civil War. Let me read again Van Dyke’s lyrics:

Jesus, thou divine Companion,

by thy lowly human birth

thou hast come to join the workers,

burden-bearers of the earth.

Thou, the carpenter of Nazareth,

toiling for thy daily food,

by thy patience and thy courage,

thou hast taught us toil is good.Where the many toil together,

there art thou among thine own;

where the solitary labor,

thou art there with them alone;

thou, the peace that passeth knowledge,

dwellest in the daily strife;

thou, the Bread of heaven, art broken

in the sacrament of life.Every task, however simple,

sets the soul that does it free;

every deed of human kindness

done in love is done to thee.

Jesus, thou divine Companion,

help us all to work our best;

bless us in our daily labor,

lead us to our Sabbath rest.

(Episcopal Hymnal 1982, No. 586)

So, I guess if we really mean it – if St. Augustine is right that the one who sings his prayer prays twice – and we expect Jesus to lead us, then I guess we really are going to have to take up our cross. We are going to have to figure out what Jesus meant when he demanded that we hate our families and our possessions. We are going to have to wrestle with whatever it was Paul was up to with Philemon and Onesimus; and we are going to have to make that decision between “life and prosperity, death and adversity.”

Deuteronomy is the last of the five books of the Law, the Torah. It is said to be Moses’ farewell discourse to the Hebrews whom he has led across the desert to the Holy Land, which they (but not he) are about to enter. He is here addressing the entire people of God. But he is not speaking to them collectively; he uses the second person singular “you” in this text. He is here speaking of a personal, not community, decision, one each person must make for him- or herself. In the words of Woodie Guthrie:

You gotta walk that lonesome valley,

You gotta walk it by yourself,

Nobody here can walk it for you,

You gotta walk it by yourself.

Moses’ advice to the Hebrews, to each individual Hebrew, is “Choose life so that you and your descendants may live, loving the Lord your God, obeying him, and holding fast to him.” Lutheran bible scholar Terrence Fretheim says of this text:

Two possible futures are laid out in this text: life and death (Deuteronomy 30:15; 30:19). Note that the future is not laid out in absolute certainty — as if God knows that future in detail and could describe it to the people right now. The future is noted in terms of possibilities. What Israel says and does will give shape to that future, but what that shape will be is not determined in advance; that future remains open to what happens within the relationship, even for God. (Working Preaching Commentary)

Fretheim points out that it is worth noting that Deuteronomy does not say how the Hebrews responded to Moses. The story is open-ended. The book, and thus the Torah, ends with uncertainty regarding what Israel’s response is or will be. Thus, this personal decision is an open-ended question not only for the Hebrews but for us today; each and every reader, every person who hears Moses read, is called to provide an response.

And that is basically what Jesus is recalling to his listeners; he is reminding the large crowd of Israelites following him on the road and he is reminding us of the stark reality of the choice Moses had set out for them and for us centuries before. He has phrased it differently, using rabbinic hyperbole, but the choice is the same: life or death; following the way of God or the way of the world symbolized by “father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters” and all of one’s possessions.

We, and I’m sure Jesus’ first listeners, are shocked by this language of “hate.” We cannot help but think of the fifth Commandment: “Honor your father and your mother” (Exod. 20:12; BCP 1979, Pg. 350) and this hardly seems consonant. We are naturally affectionate toward our parents, our siblings, and our children. But Greek scholar D. Mark Davis points out that in many instances in the Bible, in both Old and New Testaments, “hate” is used without the emotional content we habitually invest in it. Davis writes:

This use of “hate,” where there are two possibilities and one must choose decisively, seems to be the dynamic at work in our text. The full commitment to one possibility means the severance of commitment to another possibility. (Left Behind and Loving It: Holy Hating)

What is demanded by Jesus is not enmity and malice, but rather detachment. How is this to be acted out? Davis suggests:

[T]his call to discipleship is radical, implying that those who follow Jesus are not going to be making decisions based on “what’s best for me,” or even “what’s best for our marriage/family/children.” It may mean living in that “dangerous neighborhood” or attending a less achieving school, because a gracious presence is needed there. It may mean living more simply because one’s resources can be used better for others. It may mean making unpopular choices despite the protests of one’s family. This is real and critical engagement that Jesus is talking about, a stark contrast to the typical depiction of “the happy Christian home” where one’s faith is demonstrated by how committed on is to providing every possible advantage to one’s own. That kind of choosing, it seems to me, has to be cast in the strongest language possible, because we will domesticate the gospel and make it a matter of enhancing ourselves and our families until we hear this kind of extreme language and let it shake us. (Ibid.)

Using parallel structure, Jesus offers a second metaphor to explain his expectations: “Whoever does not carry the cross and follow me cannot be my disciple.” Again, we must wrestle with what this means, especially because it is so often twisted by the popular expression, “It’s my cross to bear,” making it almost equivalent to another popular expression which twists Paul’s complaint of “a thorn in my flesh.” (2 Cor 12:7) But as seminary professor Karoline Lewis reminds us, carrying the cross “cannot only be located in suffering and sacrifice when the biblical witness suggests otherwise.” (Dear Working Preacher: Carrying the Cross) In terms echoing Mark Davis’ interpretation of what it means to “hate” our families, Lewis says:

[C]arrying your cross is a choice and ironically, it is a choice for life and not death. But here is the challenge. We tend toward saying the cross is a choice for life because it leads to resurrection. Yes. And no. Yes, this is what God has done – undone death for the sake of life forever. But no, if that reality has no bearing on your present. (Ibid.)

Thus, to “carry the cross”

. . . could mean to carry the burdens of those from whom Jesus releases burdens. It could mean to carry the ministry of Jesus forward by seeing those whom the world overlooks. It could mean favoring and regarding the marginalized, even when that action might lead to your own oppression. (Ibid.)

It might mean defending equal rights and complete justice for all people in all stations of life, a living wage, abatement of poverty, worker protections, arbitration, shortened workdays, safer working conditions, the abolition of child labor, protection of voting rights, and assistance to the elderly and incapacitated, even if that might lead to higher taxes.

And that is the reality that Paul lays before Philemon in his letter returning the slave Onesimus to his household. Paul addresses Philemon as a “dear friend and co-worker,” as a leader of a church group that meets in his home, as someone filled with “love for all the saints and . . . faith toward the Lord Jesus.” And then like Moses addressing each of the Hebrews individually, like Jesus addressing the Israelites following him on the road, Paul says to Philemon, “You have a choice to make.” In his case, of course, the choice is whether to free Onesimus.

The traditional understanding of the situation addressed in this letter is that Onesimus (whose name means “Useful,” by the way) had run away, had somehow come into Paul’s service during Paul’s imprisonment, and was now being sent back to his owner. The letter doesn’t actually describe the situation that way, but verse 18 (“If he has wronged you in any way, or owes you anything, charge that to my account.”) is taken to support that view. Another interpretation of the text, however, is that Philemon had sent Onesimus to Paul for a period of time and Paul, honoring that time limit, is returning him: “I am sending him, that is, my own heart, back to you,” writes the apostle.

In any event, Onesimus is a slave who, like his master, has become “a beloved brother … in the Lord.” Onesimus in his conversion, in his “transformation is a vivid embodiment of the gospel. He is a walking reminder of the power of the good news.” (Eric Barreto, Commentary)

According to seminary professor Eric Barreto,

For Paul, what happens in these Christian communities [like the one that meet is Philemon’s home] is a matter of life and death. His letters are not just doctrinal. He’s not just concerned with ideas, with the right Christological or theological or eschatological perspective. Paul is a pastor, remember. He cares for these communities because these communities are seeds of the resurrection, sites where the resurrected life can already flourish, places of resistance to an empire that would place us in rank according to social status. (Ibid.)

And so he places before Philemon a choice, not unlike the decision Moses laid before the Hebrews, not unlike the choice Jesus gave those folks following him on the road. It no longer matters who Onesimus’ or Philemon’s father or mother may have been, who their children or their siblings are. It no longer matters what they possess; what matters is who possesses them. They have both been baptized into the Body of Christ; they are both belong to the Lord of life.

Professor Fretheim pointed out that we are not told what decision the Hebrews made and so their choice becomes an open-ended question. Likewise, we are not told what the people on the road with Jesus chose, nor do we know what Philemon decided to do. In each story, the choice is the same – life or death – and each story calls us to make the same choice.

For generations, the Jews have had a toast: “L’Chaim!” It simply means “To Life!” Every time I read this letter, I can almost see Paul putting down his pen as he finishes writing, reaching for his cup, lifting it up to the absent Philemon, and offering the toast unspoken in the letter itself: “L’Chaim! Choose life! Take up your cross! Set Onesimus free!”

Every task, however simple,

sets the soul that does it free;

every deed of human kindness

done in love is done to thee.

Jesus, thou divine Companion,

help us all to work our best;

bless us in our daily labor,

lead us to our Sabbath rest.

Let us pray:

Almighty God, you have so linked our lives one with another that all we do affects, for good or ill, all other lives: So guide us in the work we do, that we may do it not for self alone, but for the common good; and, as we seek a proper return for our own labor, make us mindful of the rightful aspirations of other workers, and arouse our concern for those who are out of work; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. (BCP 1979, Pg. 261)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

When I was practicing law and serving as the chief legal officer of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, there was a church member (of another congregation than mine) who always greeted me with a lawyer story. “What’s the difference between a lawyer and ….? ” “There was a lawyer who went to heaven ….” I think I’ve heard all the lawyer jokes, and I considered starting with one this morning. If I had had more than a passing acquaintance with Jim McKee, I might have done so. But I didn’t know Jim, so I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll begin with some poetry.

When I was practicing law and serving as the chief legal officer of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, there was a church member (of another congregation than mine) who always greeted me with a lawyer story. “What’s the difference between a lawyer and ….? ” “There was a lawyer who went to heaven ….” I think I’ve heard all the lawyer jokes, and I considered starting with one this morning. If I had had more than a passing acquaintance with Jim McKee, I might have done so. But I didn’t know Jim, so I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll begin with some poetry. What is Jesus up to? Why is he doing this?

What is Jesus up to? Why is he doing this? As many of you know, Evie and I were privileged to make a pilgrimage to the holy places of Palestine summer before last and one of the sites we visited was Mt. Tabor, the traditional “Holy Mountain” on which the Transfiguration is believed to have taken place.

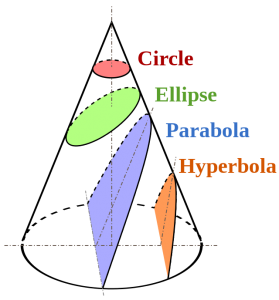

As many of you know, Evie and I were privileged to make a pilgrimage to the holy places of Palestine summer before last and one of the sites we visited was Mt. Tabor, the traditional “Holy Mountain” on which the Transfiguration is believed to have taken place. Before we tackle today’s lessons from Scripture, we’re going to recall (or perhaps learn for the first time) something from geometry class. First, I want you to envision a cone. You know what a cone is: A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base to a point called the apex or vertex; or another way of defining it is the solid object that you get when you rotate a right triangle around one of its two short sides. So, envision one of those.

Before we tackle today’s lessons from Scripture, we’re going to recall (or perhaps learn for the first time) something from geometry class. First, I want you to envision a cone. You know what a cone is: A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base to a point called the apex or vertex; or another way of defining it is the solid object that you get when you rotate a right triangle around one of its two short sides. So, envision one of those.  As I read the lessons for today, I had one of those weird little flashes of memory when some small bit of trivial knowledge you had forgotten you knew floats to the surface . . . . In this case it was something from my 9th Grade American History class. My American History teacher loved to fill us up with the minutiae of our country’s past and the one that came to mind is the debate over what to call the President of the United States: the Founders had to determine how the president was to be introduced. There were, apparently, some who favored “His Democratic Majesty, by the Grace of God, President of the United States.” Other senators recommended “His Elective Majesty” and John Adams recommended the title: “His Highness, the President of the United States and Protector of their Liberties.” All of this embarrassed George Washington who would have none of it; he wanted simply to be called “the President of the United States” and to be addressed as “Mr. President.” And thus it has been since then. The American president doesn’t even get “Your Excellency” as the presidents of other nations do.

As I read the lessons for today, I had one of those weird little flashes of memory when some small bit of trivial knowledge you had forgotten you knew floats to the surface . . . . In this case it was something from my 9th Grade American History class. My American History teacher loved to fill us up with the minutiae of our country’s past and the one that came to mind is the debate over what to call the President of the United States: the Founders had to determine how the president was to be introduced. There were, apparently, some who favored “His Democratic Majesty, by the Grace of God, President of the United States.” Other senators recommended “His Elective Majesty” and John Adams recommended the title: “His Highness, the President of the United States and Protector of their Liberties.” All of this embarrassed George Washington who would have none of it; he wanted simply to be called “the President of the United States” and to be addressed as “Mr. President.” And thus it has been since then. The American president doesn’t even get “Your Excellency” as the presidents of other nations do.