====================

A sermon offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Third Sunday in Lent, February 28, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Exodus 3:1-15; Psalm 63:1-8; 1 Corinthians 10:1-13; and St. Luke 13:1-9. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

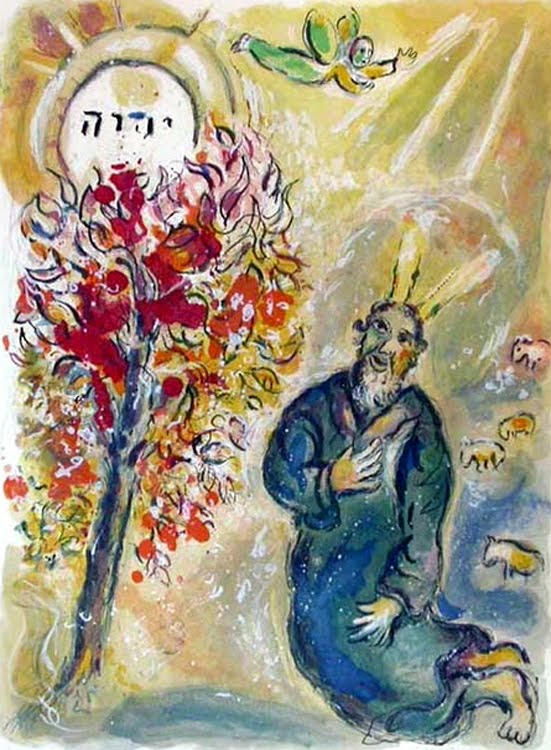

Moses is told to remove his sandals as he stands before the Burning Bush: “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” (Ex 3:5)

Moses is told to remove his sandals as he stands before the Burning Bush: “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” (Ex 3:5)

Draw away the covering that has protected you. Clear away the barrier between yourself and the earth so that your bare feet may touch and sink and take root in this holy ground. Let this living soil coat your skin. Dig in, feel your way, and find your balance here upon this mountain, so that its life becomes your life, its fire your fire, its sacred sand and loam and rock the ground of your seeing, speaking, and calling. (Anathea Portier-Young, Assoc Prof, Old Testament, Duke Divinity School, Durham, NC)

Those of us taking part in the Growing a Rule of Life Lenten study program were asked, in the second week, to consider the “soil” in which our spiritual life is rooted, to think about the people, institutions, situations, and circumstances that form the ground out which the person we are has grown. I didn’t think of it as I was working through that exercise, but perhaps we ought to have thought of metaphorically “removing our sandals” as Moses is instructed to do, of digging our toes into that rich, holy soil of our pasts in which we are planted and from which we draw much of what sustains us.

This is the metaphor that Jesus uses today when he is confronted by some of his followers about the problem known to theologians as “theodicy,” the problem so aptly put in the title of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s popular book of a few decades ago: “Why do bad things happen to good people?” (When Bad Things Happen to Good People)

Let’s back up a few verses and situate ourselves with Jesus and his followers. He has been teaching them about God’s grace (reminding them of the birds of the air and the lilies of the field), about the need for realistic preparation (telling the parable of the foolish rich man who built barns to store his excess not realizing he would soon parish and lose everything, as well as the story of the unfaithful servant caught unawares by the unexpected return of his employer), and about the divisive nature of the gospel (admonishing them that his disciples are likely to find themselves at odds with members of their own families). He has finished this series of teachings with a pointed remark about his listeners’ lack of understanding: “You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky, but why do you not know how to interpret the present time? And why do you not judge for yourselves what is right?” (Lk 12:56-57)

Apparently some of them, trying to assert their theological savvy, bring up an incident involving some Galileans who were killed while at worship in the Temple. We don’t actually have any history of this episode, but scholars surmise that these pilgrims were, perhaps, accused of some insurrection and that Pilate had sent troops into the Temple precincts who killed them as they were making their sacrifices thus “mingling” their blood with that of the animals they had offered. Such cruelty and desecration would not have been out of character for Pilate. In any event, these people bring this episode up with Jesus as if to demonstrate their understanding of sin and divine retribution.

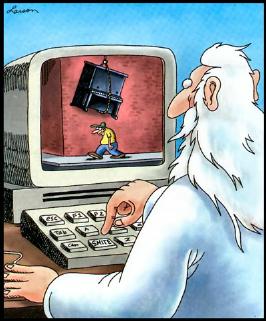

Some years ago the cartoonist Gary Larson published a cartoon of an old white-bearded judgmental God sitting at his computer terminal watching the live-streaming video of some feckless and unsuspecting sinner walk under a piano suspended from a crane while God’s finger is poised over a button on the keyboard labeled “Smite”. This seems to be the God these folk are describing to Jesus, a bookkeeper god who keeps a running tally of the good things and bad things we may do and then at some arbitrary point pushes the “Smite” button and puts paid to our cosmic account. This is the god of those who ask “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” when something bad happens to them. This is the god of those who say “Everything happens for a reason” when something bad happens to someone else. This is the picture of God that Jesus rejects utterly and completely.

Some years ago the cartoonist Gary Larson published a cartoon of an old white-bearded judgmental God sitting at his computer terminal watching the live-streaming video of some feckless and unsuspecting sinner walk under a piano suspended from a crane while God’s finger is poised over a button on the keyboard labeled “Smite”. This seems to be the God these folk are describing to Jesus, a bookkeeper god who keeps a running tally of the good things and bad things we may do and then at some arbitrary point pushes the “Smite” button and puts paid to our cosmic account. This is the god of those who ask “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” when something bad happens to them. This is the god of those who say “Everything happens for a reason” when something bad happens to someone else. This is the picture of God that Jesus rejects utterly and completely.

Probably to his listeners’ surprise, Jesus does not congratulate them on their understanding. Instead, he challenges them. “What?” he asks, “Do you think those people cut down in the Temple were worse sinners than all other Galileans?” And he ups the ante by mentioning another story that might have been running in the current edition of the local equivalent of the Medina County Gazette, the local tragedy of eighteen people killed with an old and poorly-constructed stone tower fell on them. “What about them?” he asks, “Were they any less righteous than all other Jerusalemites?”

And he answers his own questions, “No, they weren’t. They were no worse than anyone else and, guess what, you’re no better.” If there were bumper stickers in ancient Israel, Jesus might have quoted one that has been popular in our country for several years: in two words it says, sort of, “Stuff happens.” That is Jesus’ message to his listeners, the consoling news that when bad stuff happens, it is not punishment for our sins or for anyone else’s. Of course, that carries with it the corollary that when good stuff happens, it is not a reward for our righteousness. Stuff – good, bad, and indifferent stuff – just happens. And we need to be ready for it . . . that, I think, is the meaning of Jesus’ less-than-consoling follow-up comment: “Unless you repent, you will all perish as they did.”

Is Jesus threatening them or us with a suddenly collapsing roof or homicidal security forces? I don’t think so. Rather, he is encouraging us, as he had in the conversation which led up to this discussion, to prepare, to repent, to get ready, else like those who died in the Temple or under the falling tower, we will die (in the words of the Great Litany) “suddenly and unprepared.” We will die, not because of our sinfulness, but still mired in it, still not ready for whatever it is that will come after. “Stuff happens; be ready for it,” is Jesus’ message.

The consolation Jesus offers is in the parable of the fig tree which he then adds. It’s a parable we are all familiar with and one which, I’m sure, we’ve heard interpreted in the way in which Professor R. Alan Culpepper summarizes the teaching of many Christian interpreters who “have been quick to see allegorical meanings in the parable. The fig tree and the vineyard represent Israel, the owner is God, the gardener is Jesus, and the three years refer to the period of Jesus’ ministry.” (New Interpreter’s Bible, Abingdon:Nashville, 1995, Vol. IX, p 271) In fact, I found just such an interpretation in the commentary of a Baptist theologian who wrote:

We can surmise that the barren fig tree represents the people of God, including Jesus’ listeners, who are not bearing the fruit of repentance. *** God is frustrated with the lack of repentance that characterizes his people, and he is losing patience with them. Jesus may take on the role of the gardener who urges forbearance and one more chance for change and growth. His presence among them, including his teachings and miraculous works, are like the extra attention the gardener gives to the tree by digging around its base and spreading manure to nourish the soil and the roots. However, even the gardener recognizes time is limited. (Dr. Angela Reed, Asst Prof, Practical Theology, George W. Truett Theological Seminary, Waco, TX)

That’s certainly the sort of understanding of this parable that I learned in Sunday school, and if we divorce it from its context, if we don’t take into account the conversation that preceded it, that interpretation sort of makes sense. But Jesus’ has just finished telling us that God doesn’t operate that way, that God doesn’t cut down fruitless trees, that God doesn’t crush unproductive vines, that God doesn’t keep accounts and pay back sinfulness or lack of righteousness with calamities as punishment. So, I don’t think that allegorical reading makes any sense.

So who might the owner, the gardener, and the tree be . . . ?

When Lent began, we were reminded of this claim of ownership: “And the devil said to [Jesus], ‘To you I will give their glory and all this authority; for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please.’” (Lk 4:6) Now, granted, the devil is “the father of lies” (Jn 8:44) and we can’t trust a thing he says, but the author of the Second Letter to the Corinthians seems to confirm Satan’s claim when he calls him “the god of this world [who] has blinded the minds of the unbelievers.” (2 Cor 4:4)

There’s your vineyard owner: Satan. It’s Satan, not God, who is the bookkeeper. It was that wily old serpent in the Garden who suggested to Adam and Eve that it wasn’t fair that only God should have the knowledge of good and evil, that they should balance things out by eating the fruit and becoming like God. It was Satan, going to and fro in the world, who argued that Job would answer calamities with curses, balance books between him and God. It is Satan who convinces humankind that the universe should make sense, or . . . if you don’t need that personification of evil, it’s our own human desire for the cosmos to balance on scales of our own creation. We want the world to make sense on our terms. Cancer kills innocent children and we demand that there be a reason for that: it’s not comfortable to face the chaotic and unpredictable reality that “Stuff happens.” Religious fanatics bomb innocent civilians out of their homes and the world is awash in refugees and we want someone to pay the price. Playground bullies grow up to be successful real estate tycoons and powerful politicians, and we want that to make sense.

We long for a universe in which the cosmic spreadsheet tallies up the good and adds up the bad and somehow comes out at least balanced or, preferably, maybe a little bit to the good. It is our own sense of fairness, our own need for equilibrium that owns the garden. But a world of equilibrium, where everything balances according to our human sense of fairness or good bookkeeping would not be the natural world. At best, it would be a mechanistic cosmos, a machine churning out rewards and retributions, a universe fit for automata but not for flesh-and-blood human beings. I was reminded recently of a poem by D.H. Lawrence entitled The Healing:

I am not a mechanism; an assembly of various sections.

And it is not because the mechanism is working wrongly, that I am ill.

I am ill because of wounds deep to the soul, to the deep emotional self

and the wounds to the soul take a long, long time, only time can help

And patience, and a certain difficult repentance,

Long difficult repentance, realization of life’s mistake, and the freeing oneself

from the endless repetition of the mistake

Which mankind at large has chosen to sanctify.

We are all ill from wounds to the soul and we have all sanctified that same mistake: the self-destructive mistake of yearning for and trying to create the balance-sheet world of “fairness.” To paraphrase cartoonist Walt Kelly’s Pogo the possum, “We have met the bookkeeper, and he is us.”

We are the ones who would chop down the fruitless tree and uproot the unproductive vine. The tragedy is that we are also the tree! Standing there with our account books in hand, it is our own lives over which we stand in judgment: “Why me? What did I do to deserve this? Everything happens for a reason!” So disappointed are we in the stuff that happens (or doesn’t happen) that we are so often ready to uproot everything, chop it all down, start over in hopes that next time the accounts will show a profit, or at least be in balance. That’s when God the gardener steps in and says to the garden owner in us, “Hold on! Give it another year.” That’s when God says to the tree in us, “Take off your sandals; you are standing on holy ground. Dig your toes into the soil of your life. I’ll add some things here to nourish you: people who love you, a church community that supports you, a natural environment to sustain you. Take root; be nurtured; bear fruit!”

That’s when we realize that, indeed, our souls thirst for God, our flesh faints for God, that we have been like trees in a barren and dry land where there is no water. (Ps 63:1) But, with our shoes removed, our toes digging into the soil of God’s holy place, finding our balance upon God’s holy mountain, we realize that, in the midst of all the stuff that happens, the great I AM, God who is who God is, the Lord, the God of our ancestors, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, will be with us, not just for a year or three years, but for all generations. (Ex 3:15) “God is faithful, and he will . . . provide the way [for us] to endure.” (1 Cor 10:13) In the midst of all the stuff that happens, God will dig into the soil of our lives, and put nutrients on our roots, and we will bear fruit.

“Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” (Ex 3:5) Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra!

Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra! For the past several days, the Daily Office Lectionary has required us to read sections of the Book of Joshua detailing the conquest of the land “from the Jordan to the Great Sea in the west.” I have dutifully read those lessons every day. I have been deeply troubled by them and by the suggestion (which I have seen some make on Facebook and other online sources) that the “history” set out in the Book of Joshua demonstrates God’s approval of the conquest of “biblical Israel” by the modern state of Israel. I have avoided writing anything about these lessons in these daily reflections on this blog.

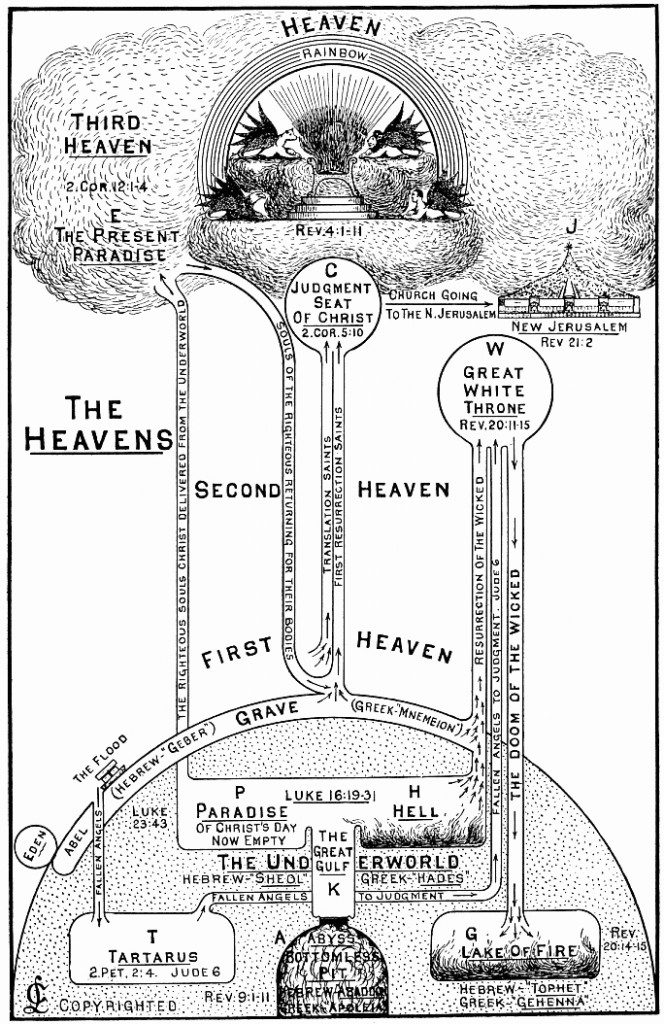

For the past several days, the Daily Office Lectionary has required us to read sections of the Book of Joshua detailing the conquest of the land “from the Jordan to the Great Sea in the west.” I have dutifully read those lessons every day. I have been deeply troubled by them and by the suggestion (which I have seen some make on Facebook and other online sources) that the “history” set out in the Book of Joshua demonstrates God’s approval of the conquest of “biblical Israel” by the modern state of Israel. I have avoided writing anything about these lessons in these daily reflections on this blog. The third heaven? Secret unrepeatable knowledge? What sort of theology are we to create out this?

The third heaven? Secret unrepeatable knowledge? What sort of theology are we to create out this? The simple answer is that fasting is going without some or all food or drink or both for a defined period of time. An absolute fast is abstinence from all food and liquid for a period of at least one day, sometimes for several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive, limiting particular foods or substance. The fast may also be intermittent in nature; for example, Muslims fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan which is intended to teach Muslims patience, spirituality, humility, and submissiveness to God. Fasting as a spiritual practice is common to all major religions. Mahatma Gandhi once noted:

The simple answer is that fasting is going without some or all food or drink or both for a defined period of time. An absolute fast is abstinence from all food and liquid for a period of at least one day, sometimes for several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive, limiting particular foods or substance. The fast may also be intermittent in nature; for example, Muslims fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan which is intended to teach Muslims patience, spirituality, humility, and submissiveness to God. Fasting as a spiritual practice is common to all major religions. Mahatma Gandhi once noted: