====================

This sermon was preached on the Fourth Sunday in Lent, March 30, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: 1 Samuel 16:1-13; Psalm 23; Ephesians 5:8-14; and John 9:1-41. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Two weeks ago our Gospel lesson was the story of Nicodemus with whom Jesus discussed birth. Jesus talked about being born anew, being born of spirit, but Nicodemus could only think of physical birth and talked about crawling back into his mother’s womb. The words were all about birth, but the lesson wasn’t really about birth, at all. It was, as we all know, about a new life in Christ, about becoming a new person through the power of God.

Two weeks ago our Gospel lesson was the story of Nicodemus with whom Jesus discussed birth. Jesus talked about being born anew, being born of spirit, but Nicodemus could only think of physical birth and talked about crawling back into his mother’s womb. The words were all about birth, but the lesson wasn’t really about birth, at all. It was, as we all know, about a new life in Christ, about becoming a new person through the power of God.

Last week, we heard the story of the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well. Jesus asked her for a drink and they talked about water. Jesus said that he could supply living water and that whoever drank it would never be thirsty and would live forever; she thought he was talking about physical water, so she asked for some so that she wouldn’t have to come to the well everyday. The words were all about water, but the lesson wasn’t really about water, at all. It was, as we all know, about sustaining the life of begun in new birth, about the constant refreshment of one’s spirit through the power of God.

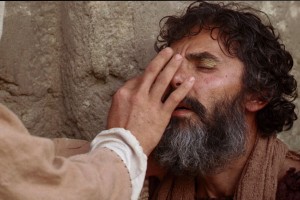

Today, we have the story of the man born blind whom Jesus cures by applying a poultice of mud made with dust and spittle. The disciples want to know why he is blind: is it because he sinned or because his parents sinned. The people who knew the man as a blind beggar want to know if it’s really him: they don’t recognize him when he comes back to them sighted. The Pharisees want to know if any law was broken when his sight was restored: it happened on a sabbath and the healing might have constituted work. The words are all about blindness and sight, but . . . guess what? . . . the lesson isn’t really about sight or blindness, at all. So what’s this story about?

Let’s leave that question for a moment and remember what day this is, why it is we have flowers on the altar in the middle of Lent, why (if we had them) we would be using rose colored vestments today, and why (if we were the Crawleys of Downton Abbey) the servants would be away today. The answer to all those questions is that today is Mid-Lent, the fourth Sunday of the season, sometimes called Laetare Sunday or Refreshment Sunday or Mothering Sunday.

That Latin name (which means “Rejoicing Sundy”) comes from the practice of the medieval church which used, on Fourth Lent, an opening sentence derived from the Prophet Isaiah to begin the Mass

Laetare Jerusalem: et conventum facite omnes qui diligitis eam . . . .

Rejoice, O Jerusalem: and come together all you that love her . . . .

With this admonition to “rejoice,” the sobriety of Lent was lessened which was liturgically symbolized by replacing the penitential purple or violet vestments with rose colored garb for the clergy. Of interest to us in connection with our Gospel lesson, however, is the second admonition of the medieval introit: “Come together all you who love her.” Keep that in mind.

The name “Mothering Sunday” may come from the traditional epistle lesson read on this Sunday prior to the advent of the new lectionaries. In the English church, that lesson came from the Letter to the Galatians in which St. Paul refers to Jerusalem as “our mother” (Gal. 4:26). Perhaps because of that lesson, a tradition began in the early Renaissance (if not earlier) of people returning to their mother church, either the place where they were raised or the cathedral of their diocese. This was a particularly British and Irish tradition, but it was also observed in some places in continental Europe. Those who made the trek were commonly said to have gone “a-mothering,” hence the name Mothering Sunday. As the tradition continued, it became a custom of the aristocracy to give the day to their domestic servants as a day off to visit their mother church, and their own mothers and families. It also became a tradition for children to pick wild flowers along the way to place in the church or to give to their mothers, so we have flowers in church. Visiting one’s place and family of origin, then, is another hint, I think, to the meaning of today’s Gospel lesson.

Because of the gathering of families on Mothering Sunday, the Lenten fast was relaxed and it became known as “Refreshment Sunday.” There are special baked treats made for this day called “Simnel Cakes” and “Mothering Buns.” The first is an almond paste and candied fruit bread similar to, but not as heavy as, fruitcake. The second are sweet rolls topped with white icing and multi-colored sprinkles known in England as “the hundreds and thousands.” It’s believed that both traditions, like others I’ve mentioned, stem from a biblical passage traditionally used on this Sunday, in this case the feeding of the five thousand (John 6:5-14). Another old name for this day is “the Sunday of the Five Loaves” which these cakes represent.

A last “fun fact” about the Fourth Sunday in Lent. There is, for example, a very peculiar English custom associated with it called “clipping the church.” The word “clipping,” however, has nothing to do with cutting or with coupons in the newspaper; it is apparently from the an old Anglo-Saxon word meaning to clasp or to embrace. In “clipping the church,” the congregation form a ring around their church building and, holding hands, embrace it. If the weather were better (and the building smaller), I’d suggest we do that! (Apparently, “clipping the church” is also done on Shrove Tuesday and on the Monday of Easter week. I’m not sure why it’s ever done!)

So what do all these traditions of the Fourth Sunday in Lent have in common: an introit admonishing those who love Jerusalem to gather together; a tradition of return home and gathering with one’s family; special cakes commemorating the feeding of 5,000 people on a hillside in the Holy Land; and the members of a congregation holding hands and embracing their church building. If I were to suggest one word to name the commonality, it would be “community.” And I want to suggest to you that community is what the story of the healing of the man blind from birth is all about, although everyone in the story (other than Jesus) is unable to appreciate that, just as Nicodemus did not appreciate that the conversation about birth was not about birth and the Samaritan woman did not understand that the discussion of water was not about water.

So it’s about community in a sort of negative way . . . when the blind man is healed he goes back home to his neighborhood, and what happens?

The neighbors and those who had seen him before as a beggar began to ask, “Is this not the man who used to sit and beg?” Some were saying, “It is he.” Others were saying, “No, but it is someone like him.” He kept saying, “I am the man.” But they kept asking . . . . (Jn. 9:8-10)

They don’t even recognize him! Without the defining characteristic of his handicap, they can’t relate to him; they don’t even know who he is! Some community, huh?

And then, once he convinces them that he is who he says he is, what do they do? They question the process and the procedure and the legality of the healing. They take him to the Pharisees, to whom he has to give a detailed explanation of the mud, and even with that the Pharisees suggest that he’s lying to them, or that his parents were lying, that he wasn’t ever really blind: “The Jews did not believe that he had been blind and had received his sight until they called the parents of the man who had received his sight and asked them.” (Jn 9:18) And when they are finally convinced that he was blind and has been given his sight, they say it isn’t legal because Jesus did it on the Sabbath. And, in the end, this poor man, whose healing should be a source of rejoicing and celebration, is not embraced by his community; he is expelled! “And they drove him out.” (Jn. 9:34)

It’s really quite sad. This miraculous thing happens in their midst — “Never since the world began has it been heard that anyone opened the eyes of a person born blind” (Jn. 9:32) — and not a single one of them praises God for the healing. No one says, “Hallelujah!” No one congratulates the man who now has his sight! No one, not even his parents, says, “That’s great! We’re pleased.” The eyes of one man were opened . . . but because those around him could not see the wonder there was nothing but turmoil. Some community, huh?

In this awful way, this negative way, this story is not about blindness; it’s not about sight. It’s about community or, really, the failure of community. It underscores by their pronounced absence the terrible important of all the things the old medieval and renaissance traditions of this Fourth Sunday of Lent emphasize: gathering with family, rejoicing with friends, embracing the church, being in community.

Let us pray:

Heavenly Father, open our eyes that we may see you in our families, in our churches, in our communities, in the lives of all our sisters and brothers; open our minds that we may understand their sorrows and their pain, their hopes and their dreams, their triumphs and their joys; open our hearts to give generously of ourselves; grant us wisdom to respond effectively to the needs of your people with grace and compassion, to their blessings with thanksgiving and delight; give us the courage to speak your words of life, peace, love, mercy, gratitude, and human community; through him with whom in the company of the Holy Spirit you form the community we call the Trinity, our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

My parish is currently undertaking a building renovation which will include redoing some of the concrete pathways and landscaping. In the process of overseeing this work, I’ve learned a new word – hardscape – which means the area of a designed landscape made up of hard wearing materials such as stone, concrete, and similar construction materials. I’ve been thinking about rocks and stones for the better part of a month. That’s why I haven’t written one of these meditations . . .

My parish is currently undertaking a building renovation which will include redoing some of the concrete pathways and landscaping. In the process of overseeing this work, I’ve learned a new word – hardscape – which means the area of a designed landscape made up of hard wearing materials such as stone, concrete, and similar construction materials. I’ve been thinking about rocks and stones for the better part of a month. That’s why I haven’t written one of these meditations . . .  I often find myself intrigued by the lesser characters we find in the Bible. At one time I started a project of writing short stories, sort of fictional midrash about some of them, but that project never went very far. Still, when a reading includes mention of someone I’ve not noticed before, it stirs my curiosity and my imagination.

I often find myself intrigued by the lesser characters we find in the Bible. At one time I started a project of writing short stories, sort of fictional midrash about some of them, but that project never went very far. Still, when a reading includes mention of someone I’ve not noticed before, it stirs my curiosity and my imagination. This advice not to worry about his donkeys is given by Samuel to Saul when Saul arrives at Ramah. It seems oddly out of place. Saul has been sent by God to Samuel, and God has informed Samuel that the man he will have sent to him is to be king over Israel. So Saul has had his cook set aside a special portion of meat and otherwise prepared to meet and anoint the man who would one day rule the country. Samuel comes to the town where he expects to find the man of God, and this statement is part of their first conversation:

This advice not to worry about his donkeys is given by Samuel to Saul when Saul arrives at Ramah. It seems oddly out of place. Saul has been sent by God to Samuel, and God has informed Samuel that the man he will have sent to him is to be king over Israel. So Saul has had his cook set aside a special portion of meat and otherwise prepared to meet and anoint the man who would one day rule the country. Samuel comes to the town where he expects to find the man of God, and this statement is part of their first conversation: “. . . the duties of the priests to the people . . . ”

“. . . the duties of the priests to the people . . . ”  Today, it is the evening psalm that I ponder.

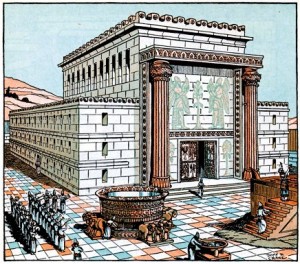

Today, it is the evening psalm that I ponder. On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated.

On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated. Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world.

Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world.