====================

A sermon offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Fifth Sunday of Easter, April 24, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Acts 11:1-18; Psalm 148; Revelation 21:1-6; and St. John 13:31-35. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Dr. Robert Waldinger is the current director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development which is something called “a longitudinal cohort study” in which the same individuals are observed over a long study period. It is the longest running study of this kind in history. For 75 years researchers have tracked the lives of 724 men from all walks of life.

Dr. Robert Waldinger is the current director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development which is something called “a longitudinal cohort study” in which the same individuals are observed over a long study period. It is the longest running study of this kind in history. For 75 years researchers have tracked the lives of 724 men from all walks of life.

Last November, Dr. Waldinger gave a TED talk entitled What makes a good life? in which he drew on the results of the Harvard study. This is some of what he said:

The clearest message that we get from this 75-year study is this: Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.

We’ve learned three big lessons about relationships. The first is that social connections are really good for us, and that loneliness kills.

And we know that you can be lonely in a crowd and you can be lonely in a marriage, so the second big lesson that we learned is that it’s not just the number of friends you have, and it’s not whether or not you’re in a committed relationship, but it’s the quality of your close relationships that matters. It turns out that living in the midst of conflict is really bad for our health.

And the third big lesson that we learned about relationships and our health is that good relationships don’t just protect our bodies, they protect our brains.

Over and over, over these 75 years, our study has shown that the people who fared the best were the people who leaned into relationships, with family, with friends, with community.

The good life is built with good relationships.

So . . . last week I began my sermon by trying to sing Led Zeppelin’s classic rock song Stairway to Heaven and, in the homily, I suggested to you that, unlike the lady in the song, we do not need to buy or build such a stairway because the good news of Jesus’ Gospel is that heaven is already here: “The kingdom of heaven has come near.” (Mt 10:7) “The kingdom of God has come to you.” (Mt 12:28) It’s here; we don’t need to worry about getting there. And later in the week I got some feedback about that sermon; two people asked questions about it.

One asked, “Don’t you believe in an afterlife?” That’s the easy question to answer, “Yes, I do. But I’m not concerned about it.” I trust that Jesus was telling the thief on the other cross the truth when he said, “Today you will be with me in Paradise.” (Lk 23:4) I believe he was telling the truth to the disciples when, speaking of his own death, he told them “I go to prepare a place for you.” (Jn 14:2) I believe that the afterlife is a given and that there is nothing we need to do, indeed there is nothing we can do, to “earn” it. As the Eucharistic preface used during a requiem in the Episcopal Church says, “to [God’s] faithful people . . . life is changed, not ended; and when our mortal body lies in death, there is prepared for us a dwelling place eternal in the heavens.” (BCP 1979, page 382)

The second question was a little tougher: “What about someone whose life just sucks? How can you say to someone like that that heaven is here?” Now that’s a good question. And the answer lies in that research done by Dr. Waldinger and his colleagues and their predecessors, and in today’s Gospel lesson, particularly in Jesus’ words, “I give you a new commandment, that you love one another. Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another.” (Jn 13:34) – This is the way our New Revised Standard Version translates the Greek. There may be a better way to translate it, but let’s go with this for the moment.

Seminary professor Karoline Lewis writes of today’s Lectionary reading:

Jesus’ command to love one another is dangerously out of context. Read without its literary framework, it becomes another biblical platitude quoted by those who think it’s easy and who rarely stick to it themselves. It ends up on posters with the backdrop being some sort of idyllic scene of an ocean, snow-capped mountains, a rushing waterfall, or birds flying across a bright blue sky. It actually seems doable. (Resurrection Is Love)

But, she points out, lovely scenery and idyllic circumstances are not the context of this “new commandment.” Rather, it was given to the disciples at a time when evil seemed to be getting its way. It was spoken at the end of the Last Supper when someone Jesus and the others thought they could trust had just left to betray especially him and in reality all of them. Jesus commanded his followers to love at time “when the actions and words of others clearly [came] from hate and suspicion and prejudice;” in the words of my questioner, at a time when life sucked!

Jesus’ “new commandment,” says Prof. Lewis, “remind[s us] to choose love when evil seems to be having its way,” when life sucks. “And,” she says, “our decision to choose love does not even have to be in the face of the most overt and blatant expressions of its opposite. Our lives are full of minor incidents, if you will, when we can decide to come from a place of love rather than one of frustration and anger and judgment.”

Theologians sometimes use the word irruption when talking about the Kingdom of God. It is a word related to such ideas as eruption (a breaking out of something) and disruption (a breaking apart). Irruption means “to break into.” It conveys the idea that God’s rule, the kingdom of heaven, has broken into our reality. “The kingdom of God has come to you.” When we make the choice of love, we actualize that irruption; we make that in-breaking of heaven apparent and perceivable in a world which seems very much to the contrary.

But we are left, still, with a very serious question: How do we do that? If the “new commandment” is that we are to love one another, what does that mean? How are we to love one another? What are to be the manifestations of this love we are commanded to have?

Elizabeth Johnson, who teaches theology in Cameroon, points out that in John’s narrative the “new commandment” is bracketed by two stories of action. (Commentary) The first is Jesus washing the feet of his disciples about which he says: “If I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you.” (Jn 13:13-15) The second is the crucifixion about which Jesus says: “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. You are my friends if you do what I command you.” (Jn 15:13-14)

These two actions parallel and help to flesh out the meaning of the “new commandment”. On the one hand, “love one another” compels us to “heroic acts of great risk; it extends even to the point of giving one’s life for another.” On the other, “loving one another as Jesus has loved encompasses the mundane; it means serving one another, even in the most menial tasks.”

So that’s one way to understand the “new commandment” – that we are commanded to love one another and to act out that love in these sorts of ways. But some will object that love cannot be commanded, and that telling someone to love another and demanding that the one serve the other only breeds resentment and contempt. I know this from experience and I suspect you do, as well.

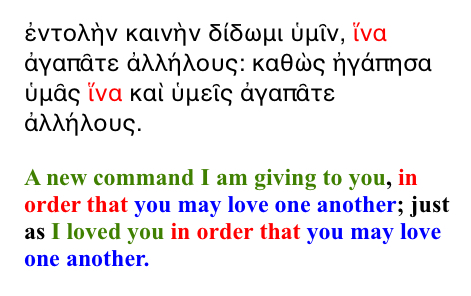

For that reason, I find the work of a Presbyterian pastor named Mark Davis compelling. Pastor Davis has a Ph.D. in theology and is very accomplished in the study and translation of Greek. He has recently made the argument that our typical translation of John is wrong and that, as a result, we haven’t properly understood the “new commandment.” It’s easier to show you his argument than it is to tell it, so I’m going to put a slide up on the big screen TV. (Commanding Love; see also ‘In Order That’ You May Love)

Here’s what we’ve got:

This is John 13:34 in the original Greek, and the lower color-coded text is Dr. Davis’s translation. The color coding helps to explain his argument.

Dr. Davis first points out that the original Greek is one sentence, not two. The translation in the New Revised Standard Version breaks it into two sentences. Second, he points out that the Greek is written in a poetic form called “parallelism,” which is the balanced and symmetrical repetition of a thought or idea in slightly different forms as a way to emphasize the message. The New Revised Standard fails to honor the parallelism and, in fact, adds an imperative that simply isn’t there. Third, he points out that the Greek word “hina” (which he has color-coded in red) has been either overlooked or possibly mistranslated.

This third point is really the most important. Pointing out that the word “hina” can be translated either as “that” or as “in order that,” and that “hina” is normally understood to specify purpose, Dr. Davis suggests the second translation, as shown here, is the better choice.

Thus, the “new commandment” is not simply “love one another.” The “new commandment” is something else that Jesus has said, done, or taught which enables us to love one another in the same way that his empowering love enables us to do so.

Therefore, Dr. Davis’ asks, “What is the new command ([of] which loving one another is the result)?” and answers his own question, “I would suggest that the whole demonstration of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet is the command.” In other words, the “new commandment” is not to love one another, it is to do what Dr. Johnson called those “mundane, menial tasks” and from that work will flow the capacity for and the actuality of loving one another, from that work will flow the actualizing and appreciation of the irruption the kingdom of God, from that work will flow the realization that “the kingdom of heaven has come near.” I know, from personal experience, that this is true.

In the spring of 1971, I was 18 years old and finishing my sophomore year of college. And I was failing, badly. So I dropped out. I went to work in a hospital where I eventually worked as an orderly, but I didn’t start out as an orderly. I started out as a janitor. Once I had learned how to clean toilets and mop floors in proper hospital fashion, I was turned loose to take care of the common areas and of the patient rooms.

Early in my employment, I became acquainted with Mr. Aronson. I have no idea what Mr. Aronson’s medical problem was . . . all I know is that whatever it was it made Mr. Aronson’s life miserable. Mr. Aronson’s digestive system was out of control. If he ate, he vomited and he had diarrhea. His doctors were trying to treat this, of course, and he had to eat to see of the treatment was working, and most of the time it seemed it wasn’t. Nearly every day I would get a call to go to Mr. Aronson’s room where I had to mop the floor of either puke or feces and to gather up soiled bed linens. I hated getting those calls. I hated going to that room. I hated mopping that smelly floor and packing up those stinking linens and, I’m sorry to say, I hated Mr. Aronson. His life sucked and it was making my life suck.

And he knew it. He knew his life miserable and that his misery was negatively impacting everyone around him. But he must have known something else because he never acted that way. He was always gracious and he was always grateful. I’d show up with my 18-year-old “I hate being here” attitude, and if he was awake he would greet me courteously. I’d mop up his puke and his diarrhea, and stuff his soiled linens into a laundry bag, and he’d thank me. I didn’t want to be there; I didn’t want to deal with his mess or his smelly sheets; and I didn’t want his gratitude. But, when you’re employed as a hospital janitor, that’s what you do.

And after several days of doing that, you stopped noticing the smell and the misery. Instead, you looked forward to the greeting and you were grateful for the gratitude. And when, after a few weeks, Mr. Aronson died because they couldn’t fix whatever was wrong with him, you wept because, you discovered, you no longer hated Mr. Aronson. You loved Mr. Aronson; he had become your friend, and your friend was gone.

Mr. Aronson, it turned out, was the rabbi of the local Reform Jewish synagogue. His wife invited all of the hospital employees who had taken care of him, even us janitors, to attend his funeral, and it was there that I first heard and first recited the prayer called The Mourner’s Kaddish:

Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name throughout the world

which He has created according to His will.

May He establish His kingdom in your lifetime and during your days,

and within the life of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon;

and say, Amen.

May His great name be blessed forever and to all eternity.

Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored,

adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He,

beyond all the blessings and hymns, praises and consolations that

are ever spoken in the world; and say, Amen.

May there be abundant peace from heaven, and life, for us

and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

He who creates peace in His celestial heights,

may He create peace for us and for all Israel;

and say, Amen.

I think that what Mr. Aronson knew that allowed him to be gracious and grateful is what I have come to know and believe: that if we will just take care of one another doing whatever mundane, menial tasks are needed, God will establish his kingdom in our lifetime and there will be abundant peace from heaven and life for all of us. From those mundane, menial tasks flows the capacity for and the actuality of loving one another, and that from that love flows the realization that “the kingdom of heaven has come near.”

Whether we understand the “new commandment” to be “love one another” or to be “do these things in order that love for one another can grow,” the point of Jesus’ “new commandment” is to foster good relationships between people, those good relationships that Dr. Waldinger’s research has shown are the foundation of a good life. I have faith that sometime in the future the kingdom of heaven will be complete and God will exercise a gracious and just control over everything in (and outside of) time and space, but I know that right now heaven is close at hand through Christians and other good people, individually and collectively, engaging the world in acts of love, both mundane and heroic.

Jesus insists that the kingdom of heaven is close at hand when we love one another. Medical science has proved it: “The good life is built with good relationships.” So I can say with confidence that heaven is here now, even for the person whose life sucks. Mr. Aronson taught me that. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

There’s a lady who’s sure

There’s a lady who’s sure In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.

In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.  Every year on the Second Sunday of the Easter season, we read the story from John’s Gospel of Thomas’s refusal to accept the testimony of his fellow disciples, but in each year of the Lectionary Cycle, it is coupled with different lessons from the Book of Acts and a different epistle lesson. So this year, in Year C of the cycle, we have heard of the confrontation between Peter and the high priest about the apostles’ teaching in the Temple, and we have heard part of the introduction of John of Patmos’ Revelation.

Every year on the Second Sunday of the Easter season, we read the story from John’s Gospel of Thomas’s refusal to accept the testimony of his fellow disciples, but in each year of the Lectionary Cycle, it is coupled with different lessons from the Book of Acts and a different epistle lesson. So this year, in Year C of the cycle, we have heard of the confrontation between Peter and the high priest about the apostles’ teaching in the Temple, and we have heard part of the introduction of John of Patmos’ Revelation.  We’ve heard this Gospel story before. We all know what happens (at least in the Synoptic Gospels) after Jesus is baptized: a voice is heard from heaven, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Lk 3:22) and then Jesus goes into the desert for forty days of retreat where he grapples with temptations.

We’ve heard this Gospel story before. We all know what happens (at least in the Synoptic Gospels) after Jesus is baptized: a voice is heard from heaven, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Lk 3:22) and then Jesus goes into the desert for forty days of retreat where he grapples with temptations.  I get letters. Sometimes they’re really nice letters. And sometimes they’re not. Today, I want to tell you about a letter and how it caused me to rethink the two stories of women in today’s lectionary readings: First, the end of the story of Ruth from the biblical book named for her, and second, the story of Jesus watching and commenting upon the sacrificial giving of a widow in the Jerusalem temple.

I get letters. Sometimes they’re really nice letters. And sometimes they’re not. Today, I want to tell you about a letter and how it caused me to rethink the two stories of women in today’s lectionary readings: First, the end of the story of Ruth from the biblical book named for her, and second, the story of Jesus watching and commenting upon the sacrificial giving of a widow in the Jerusalem temple.