====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Sunday after the Ascension, the Seventh Sunday of Easter, May 28, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are from the Revised Common Lectionary: Acts 1:6-14; Psalm 68:1-10,33-36; 1 Peter 4:12-14,5:6-11; and St. John 17:1-11. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

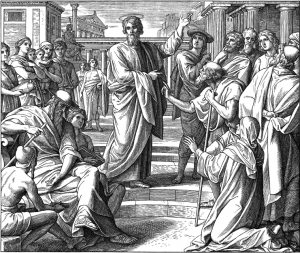

As I read our lessons for today and again as I heard them this morning, two verses in particular have leapt out at me. One from the Gospel of John in which Jesus says: “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3) The other is from the story in the Book of Acts in which, after Jesus has been lifted up and a cloud has taken him out of the apostles’ sight, two suddenly-appearing “men in white robes” (angels, one presumes) ask the apostles, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” (Acts 1:11)

As I read our lessons for today and again as I heard them this morning, two verses in particular have leapt out at me. One from the Gospel of John in which Jesus says: “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3) The other is from the story in the Book of Acts in which, after Jesus has been lifted up and a cloud has taken him out of the apostles’ sight, two suddenly-appearing “men in white robes” (angels, one presumes) ask the apostles, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” (Acts 1:11)

I want to explore the way in which these two verses are connected, but first let me ask you a question. Have you ever had a conversation that went like this?

“Hi, how are you?” asks an acquaintance.

“Fine, thanks! How are you?” you answer, but before you’ve even finished saying the word “fine” you friend has walked on and is paying not the slightest attention to you or your answer and clearly was not really interested in whether you are fine or not and is even less interested in telling you how they are doing.

What would you call the relationship such a dialogue evidences? I used the word “friend,” but that clearly overstates what such a lack of give-and-take demonstrates; I also used “acquaintance,” but I don’t think the conversation shows even that level of association. It’s more like the image in Longfellow’s The Theologian’s Tale:

Ships that pass in the night, and speak each other in passing,

Only a signal shown and a distant voice in the darkness;

So on the ocean of life we pass and speak one another,

Only a look and a voice, then darkness again and a silence.

(Tales of a Wayside Inn, 1863)

You’ve had, I suspect, many conversations of greeting like that. I know I have.

In contrast to such transient and insignificant greetings, consider the way the fictional people of the planet Pandora in the 2009 science-fiction film Avatar greeted one another. Avatar was on TV Friday night. Perhaps you saw it; I did. Avatar was a big splashy tale of the clash of cultures, rapacious exploitative humans from Earth versus the apparently primitive but wise and environmentally attuned Na’Vi of Pandora. It had lots of CGI special effects, very effective use of 3D film technology, and a good action plot that kept viewers entertained. In the midst of all that there was a story about relationships, both relationships in general and a specific relationship, the love affair between the human Jake Sully and the Na’Vi native girl Neytiri.

In the Na’Vi cosmology, all life is connected through a personalized power they call “Ey’Wa.” Ey’Wa is not God – it’s unclear whether the Na’Vi have a god, and at one point Neytiri criticizes and even ridicules Jake when he addresses a prayer to Ey’Wa – but neither is Ey’Wa the impersonal and amoral “Force” of the Star Wars saga. In the world of theology, the Na’Vi understanding is most similar to the teaching called “panentheism,” literally “all-in-God-ism.” This school of thought affirms that although God and the world are distinct, that is, not the same, and although God transcends the world, the world is, nonetheless, “in” God; God is intimately connected to the world and yet remains greater than the world. (Panentheism should not be confused with pantheism, which understands God to be the world.) Some famous theologians associated with the idea of panentheism are the Lutheran Paul Tillich, Wolfhart Pannenberg in the Reformed tradition, the Evangelical Jurgen Moltmann, and the Roman Catholic writer Karl Rahner.

In any event, the Na’Vi’s understanding of Ey’Wa and their connection to her is expressed in their greeting, “I see you.” As the Na’Vi explain in the film, this greeting doesn’t mean ordinary seeing; it means “the Ey’Wa in me sees the Ey’Wa in you; the Ey’Wa in me is connecting with the Ey’Wa in you.” That greeting conveys a much, much greater sense of relationship than any “Hi, how are you? … Fine, and you?”

The conservative Roman Catholic New York Times op-ed writer Ross Douthat didn’t like Avatar at all. The week it came out (just before Christmas in 2009), he wrote a blistering critique of the philosophical underpinnings of its story, accusing the writers of offering a world-view in which human beings are nothing more than “beasts with self-consciousness, predators with ethics, mortal creatures who yearn for immortality” in an agonized and deeply tragic position from which “there is no escape upward.” (http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/21/opinion/21douthat1.html)

Now, I often find myself in disagreement with Mr. Douthat but I also often find his prose memorable and, having read his negative critique of a movie I rather enjoyed, I often think of it when I see the movie (which I did on Friday night). And his “no escape upward” quip sort of went “click” into the socket presented by that question from today’s lesson from the Acts of the Apostles: “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?”

By far my favorite artistic representation of the Ascension is Salvador Dali’s The Ascension of Christ painted in 1958. Dali said that his inspiration for the painting

. . . came from a “cosmic dream’ that he had in 1950, some eight years before the painting was completed. In the dream, which was in vivid color, he saw the nucleus of an atom, which we see in the background of the painting; Dali later realized that this nucleus was the true representation of the unifying spirit of Christ. (Dali Paintings)

The viewer’s perspective is that of apostles, looking upwards at the bottoms of Jesus’ feet.

The feet of Christ point out at the viewer, drawing the eye inwards along his body to the center of the atom behind him. The atom has the same interior structure as the head of a sunflower. (Ibid.)

Dali explained to Mike Wallace in a 1958 television interview that he was intrigued by continuous circular patterns like sunflowers because they follow the law of a logarithmic spiral, which he associated with the force of spirit. (The Mike Wallace Interview, 4/19/1958) Dali often fused his conceptions of Christianity with the science of the mid-20th Century. So the sunflower-like nucleus of the atom was Dali’s representation of the unifying spirit of Christ, which in Dali’s nuclear mysticism connects everyone.

In the distance above the sunflower is the Dove, ready to descend from the clouds as on Pentecost which the church celebrates ten days after the Feast of the Ascension. Also there is a human face, specifically Dali’s wife Gala, who is crying. Dali often used Gala’s image to portray the Virgin Mary, the Queen of Heaven, but here she seems to represent the Father weeping over the Son’s departure from the Earth from the Father’s perspective in heaven.

So when I hear those two white-clad angels asking the men of Galilee why do they stood there looking up toward heaven, I think of Dali’s painting and I know why! There was so much to see, so much to stand in awe of, so much to be overwhelmed by! And yet the angels’ question is a poignantly valid one because, despite Mr. Douthat’s critique of the movie Avatar, there is no immediately available “escape upward.” There is, instead, this world in which we “beasts with self-consciousness, [we] predators with ethics, [we] mortal creatures who yearn for immortality” must get on with the business of living. There is this world into which Jesus sent his followers just before that moment of being lifted up with the command:

Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age. (Mt 28:19-20)

There is this world in which Jesus prayed to his Father that his followers might have eternal life, “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3)

There it is; the biblical definition of “eternal life.” Eternal life is to know God and Jesus. Professor Karoline Lewis of Luther Seminary in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in her commentary on this gospel lesson asks:

What if it is that simple? How would that change what we imagine in this life? How would it affect our thoughts about and beliefs in our future life with God? How does this alter even our picture of God? Of course, what it means to “know” God is key, and to know God in the Fourth Gospel has no connection to cognitive constructions, creedal consents, or specified knowledge about God. Rather, knowing God is synonymous with being in a relationship with God. (Working Preacher Commentary, 2014)

Another commentator on this text points out that there are

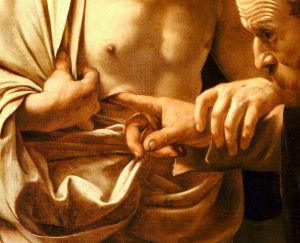

. . . four great examples of discipleship in John are the Samaritan woman in ch. 4, the blind man in chapter 9, Mary in chapter 12, and Thomas, of all people, in chapter 19? What do they have in common? They participated in ongoing relationship and encounter with Jesus. Both the Samaritan woman and the blind guy have lengthy, increasingly deep dialogue with Jesus and as they do, they understand him more and more to the point where they “know” him and understand that he is the source of their lives and loves them like no other. This leads them to worship him and testify to others about him.

Mary is described as one whom Jesus loved (11:5) and John makes it clear and that she, her brother Lazarus and sister Martha regularly spent time with Jesus. Thomas may be a less obvious hero, but he’s a hero nonetheless in this Gospel. He sticks with Jesus even though he discerns trouble is in store (11:16); he asks questions when he doesn’t understand (14:5); he’s not gullible or prone to flights of fancy but he’s willing to believe when confronted with raw glory (chapter 20). On the basis of all of this, Thomas comes to fully know Jesus such that he declares him to be “My Lord and My God” (20:28). (Jaime Clark-Soles, Working Preacher Commentary, 2008)

How do we do that? How do we come to know Jesus the way these four great disciples did? How can we emulate the woman at the well, the man born blind, Mary of Bethany, or Thomas who is wrongly called “the doubter”? Unlike them, we don’t have Jesus walking around here with us. But we do have each other. And we do have all those people out there for whom he died and rose again, and to whom he sent us. And we are commended by John in his first epistle to “love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God.” (1 Jn 4:7) And John continues, “No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is perfected in us. * * * God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” (1 Jn 4:12,16b)

Which brings me back to the two angels and their question, and to the Na’Vi and their greeting, “I see you.” Jay Michaelson, a writer for The Huffington Post, in an editorial reply to Mr. Douthat’s criticisms suggested that the Na’Vi greeting is equivalent to the Hindu Sanskrit greeting, “Namaste.” Namaste literally means, “I bow to you” and is often translated to mean more fully, “The divine in me bows to the divine in you.” That is pretty similar to the Na’Vi explanation that “the Ey’Wa in me sees the Ey’Wa in you” and I suppose the screenwriters could definitely have had that in mind.

But there is another culture in our world which uses a more direct equivalent of the Na’Vi greeting, the Samburu people of Africa’s Serengeti about whom life-coach Terry Tilman writes in his essay entitled Connecting to the Soul:

About 20 years ago I was on a safari in Africa (Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda). As we traveled through the villages and Serengeti savanna I noticed a recurring event. When one of the indigenous people would approach another, they would pause, face each other, look directly in each others eyes for 5 -15 seconds, say something and then continue on their way. This would happen in populated villages and in very remote areas where there may be only one human every 20 square miles.

After a couple weeks of noticing this I asked one of our guides from the Samburu tribe what the natives were doing. He said they were greeting each other. “How are they doing that? What are they saying?” I asked.

“One of them says, ‘I see you.’ Connecting through the eyes, the other replies, ’I am here.’”

****

My Samburu guide told me something else that I didn’t get at first. He said that in their language the greeting also meant something like, “Until you see me I do not exist. When you see me, you bring me into existence.” This speaks toward our deep connectedness and that we are in fact All One.

If you have seen Avatar, you know that the human character Jake Sully is a disabled Marine; he is confined to a wheelchair in his “real” human life. But his avatar, a synthetic body into which his conscience is temporarily transferred, is a fully functional Na’Vi male body. At the end of the movie, after Jake has rebelled against his superiors and championed the Na’Vi’s cause against Pandora’s exploitation by Earth, Jake’s crippled body is trapped in a damaged mobile laboratory. Neytiri finds him, breaks into the lab, and rescues him: “In the end, the real Jake is not his avatar. The real Jake is a man, unshaven and unkempt, without functional legs. And Neytiri sees this. As she holds the dying Jake, she tells him ‘I see you.’ This is what love is. Love is not trying to change the other person, to make them perfect, or to focus on their weaknesses. Love is seeing a person for who they are and embracing that person.” (The Everyday Thomist) Jake, of course, doesn’t die. Through a Na’Vi ritual and the connection with and through Ey’Wa, his consciousness is permanently transferred into the synthetic Na’Vi avatar, and he and Neytiri live happily ever after (one supposes).

If you have seen Avatar, you know that the human character Jake Sully is a disabled Marine; he is confined to a wheelchair in his “real” human life. But his avatar, a synthetic body into which his conscience is temporarily transferred, is a fully functional Na’Vi male body. At the end of the movie, after Jake has rebelled against his superiors and championed the Na’Vi’s cause against Pandora’s exploitation by Earth, Jake’s crippled body is trapped in a damaged mobile laboratory. Neytiri finds him, breaks into the lab, and rescues him: “In the end, the real Jake is not his avatar. The real Jake is a man, unshaven and unkempt, without functional legs. And Neytiri sees this. As she holds the dying Jake, she tells him ‘I see you.’ This is what love is. Love is not trying to change the other person, to make them perfect, or to focus on their weaknesses. Love is seeing a person for who they are and embracing that person.” (The Everyday Thomist) Jake, of course, doesn’t die. Through a Na’Vi ritual and the connection with and through Ey’Wa, his consciousness is permanently transferred into the synthetic Na’Vi avatar, and he and Neytiri live happily ever after (one supposes).

Mr. Douthat complained that the panentheism of Avatar encourages us to avert our gaze from the “escape upward” that the Christianity of his conservative understanding affords, but that is precisely what the angels’ question and Jesus’ prayer encourage us to do. Eternal life is not found in “looking up toward heaven.” Eternal life is found when we see and know God and Jesus in those around us. Eternal life comes from knowing that we are not “ships that pass in the night, and speak each other [only] in passing,” but that we are, instead, deeply connected, that (as John wrote) “God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” Eternal life comes from knowing that we are all – as Jesus prayed and as Jesus taught – one, as he and the Father are one. (Jn 17:11)

I see you.

Amen.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Our kids this week have been “Shipwrecked,” but they’ve also been “rescued by Jesus.”[1] They’ve been learning the truth of that promise emblazoned on neon crosses at innumerable inner-city rescue missions in nearly every English-speaking country in the world, “Jesus saves,” through the metaphor of being lost at sea and washed up on a deserted island. That’s something that happened to St. Paul at least three if not four times![2]

Our kids this week have been “Shipwrecked,” but they’ve also been “rescued by Jesus.”[1] They’ve been learning the truth of that promise emblazoned on neon crosses at innumerable inner-city rescue missions in nearly every English-speaking country in the world, “Jesus saves,” through the metaphor of being lost at sea and washed up on a deserted island. That’s something that happened to St. Paul at least three if not four times![2] What do you suppose it was like in Jerusalem on that Pentecost morning so long ago?

What do you suppose it was like in Jerusalem on that Pentecost morning so long ago? Our gospel lesson today is from John’s story of the last supper. This is part of a long after-dinner speech that Jesus gives including a section known as the “high priestly prayer.” In it, among other petitions, Jesus asks God the Father to look after his disciples. He prays:

Our gospel lesson today is from John’s story of the last supper. This is part of a long after-dinner speech that Jesus gives including a section known as the “high priestly prayer.” In it, among other petitions, Jesus asks God the Father to look after his disciples. He prays: Every year, for as long as any of us can remember, on the Second Sunday of Easter the church has told the story of Thomas, Thomas the Doubter, “Doubting Thomas” who wouldn’t believe that Jesus had risen, the poster child for those who are uncertain. But, believe me, Thomas gets a bad rap! He was no worse a doubter or disbeliever than any of the others, including Peter!

Every year, for as long as any of us can remember, on the Second Sunday of Easter the church has told the story of Thomas, Thomas the Doubter, “Doubting Thomas” who wouldn’t believe that Jesus had risen, the poster child for those who are uncertain. But, believe me, Thomas gets a bad rap! He was no worse a doubter or disbeliever than any of the others, including Peter! A couple of months ago, I was part of a conversation among several parishioners about the set-up for our celebrations of the Nativity. We looking at our plans for Christmas services, and a member of our altar guild exclaimed, “That’s the problem! Things are always changing around here!”

A couple of months ago, I was part of a conversation among several parishioners about the set-up for our celebrations of the Nativity. We looking at our plans for Christmas services, and a member of our altar guild exclaimed, “That’s the problem! Things are always changing around here!” Christmas is now done. It ended Friday on Twelfth Night. I am sure than none of you, good Anglican traditionalists that we all are, put away any of your decorations before then, but have by now put them all away.

Christmas is now done. It ended Friday on Twelfth Night. I am sure than none of you, good Anglican traditionalists that we all are, put away any of your decorations before then, but have by now put them all away.  Almighty God, on this day you opened the way of eternal life to every race and nation by the promised gift of your Holy Spirit who empowered the disciples to proclaim the Good News to peoples from many lands speaking many tongues: we now pray for those in many lands speaking many languages who have been hurt or killed by terrorist violence in the past fortnight in: London (England), Kabul (Afghanistan), Mosel (Iraq), Minya (Egypt), Khost (Afghanistan), Mastung (Pakistan), Gao (Mali), Borno State (Nigeria), Raqqa (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia), rural Colombia, Manila (Philippines), Baghdad (Iraq), Basra (Iraq), Portland (Oregon, USA) and Manchester (England). May God grant eternal rest to the departed, healing to the injured, and comfort to those in grief. And since Jesus taught us to love and pray for our enemies, we pray also for those who have committed these violent acts, and for those who may be contemplating additional violence. May God change their hearts and shed abroad the gift of peace throughout the world by the preaching of the Gospel, that it may reach to the ends of the earth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Almighty God, on this day you opened the way of eternal life to every race and nation by the promised gift of your Holy Spirit who empowered the disciples to proclaim the Good News to peoples from many lands speaking many tongues: we now pray for those in many lands speaking many languages who have been hurt or killed by terrorist violence in the past fortnight in: London (England), Kabul (Afghanistan), Mosel (Iraq), Minya (Egypt), Khost (Afghanistan), Mastung (Pakistan), Gao (Mali), Borno State (Nigeria), Raqqa (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia), rural Colombia, Manila (Philippines), Baghdad (Iraq), Basra (Iraq), Portland (Oregon, USA) and Manchester (England). May God grant eternal rest to the departed, healing to the injured, and comfort to those in grief. And since Jesus taught us to love and pray for our enemies, we pray also for those who have committed these violent acts, and for those who may be contemplating additional violence. May God change their hearts and shed abroad the gift of peace throughout the world by the preaching of the Gospel, that it may reach to the ends of the earth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. As I read our lessons for today and again as I heard them this morning, two verses in particular have leapt out at me. One from the Gospel of John in which Jesus says: “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3) The other is from the story in the Book of Acts in which, after Jesus has been lifted up and a cloud has taken him out of the apostles’ sight, two suddenly-appearing “men in white robes” (angels, one presumes) ask the apostles, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” (Acts 1:11)

As I read our lessons for today and again as I heard them this morning, two verses in particular have leapt out at me. One from the Gospel of John in which Jesus says: “And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3) The other is from the story in the Book of Acts in which, after Jesus has been lifted up and a cloud has taken him out of the apostles’ sight, two suddenly-appearing “men in white robes” (angels, one presumes) ask the apostles, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” (Acts 1:11) If you have seen Avatar, you know that the human character Jake Sully is a disabled Marine; he is confined to a wheelchair in his “real” human life. But his avatar, a synthetic body into which his conscience is temporarily transferred, is a fully functional Na’Vi male body. At the end of the movie, after Jake has rebelled against his superiors and championed the Na’Vi’s cause against Pandora’s exploitation by Earth, Jake’s crippled body is trapped in a damaged mobile laboratory. Neytiri finds him, breaks into the lab, and rescues him: “In the end, the real Jake is not his avatar. The real Jake is a man, unshaven and unkempt, without functional legs. And Neytiri sees this. As she holds the dying Jake, she tells him ‘I see you.’ This is what love is. Love is not trying to change the other person, to make them perfect, or to focus on their weaknesses. Love is seeing a person for who they are and embracing that person.” (

If you have seen Avatar, you know that the human character Jake Sully is a disabled Marine; he is confined to a wheelchair in his “real” human life. But his avatar, a synthetic body into which his conscience is temporarily transferred, is a fully functional Na’Vi male body. At the end of the movie, after Jake has rebelled against his superiors and championed the Na’Vi’s cause against Pandora’s exploitation by Earth, Jake’s crippled body is trapped in a damaged mobile laboratory. Neytiri finds him, breaks into the lab, and rescues him: “In the end, the real Jake is not his avatar. The real Jake is a man, unshaven and unkempt, without functional legs. And Neytiri sees this. As she holds the dying Jake, she tells him ‘I see you.’ This is what love is. Love is not trying to change the other person, to make them perfect, or to focus on their weaknesses. Love is seeing a person for who they are and embracing that person.” ( A couple of years ago Pope Francis made a cogent observation about praying for those who are hungry: “You pray for the hungry. Then you feed them. That’s how prayer works.” (

A couple of years ago Pope Francis made a cogent observation about praying for those who are hungry: “You pray for the hungry. Then you feed them. That’s how prayer works.” ( It’s the Fourth Sunday of Easter and that means it’s “Good Shepherd Sunday.” And that means that clergy throughout the church have, for the last week, been scratching their heads thinking, “This again? What can I do this time with the sheep-and-shepherd simile?” But, I’m not among them. For three days this past week, the clergy of this diocese have been in conference with our bishop, with a retired seminary president, and with a retired cathedral dean exploring exactly what we understand our ordinations to the diaconate and to the presbyterate to mean. That has kind of taken my attention off the “Good Shepherd” metaphor.

It’s the Fourth Sunday of Easter and that means it’s “Good Shepherd Sunday.” And that means that clergy throughout the church have, for the last week, been scratching their heads thinking, “This again? What can I do this time with the sheep-and-shepherd simile?” But, I’m not among them. For three days this past week, the clergy of this diocese have been in conference with our bishop, with a retired seminary president, and with a retired cathedral dean exploring exactly what we understand our ordinations to the diaconate and to the presbyterate to mean. That has kind of taken my attention off the “Good Shepherd” metaphor.