Two weeks ago, Mark told us the story of the rich man who came to Jesus asking “What must I do to inherit eternal life?”[1] Today, in contrast, we have the story of Blind Bartimaeus.

Two weeks ago, Mark told us the story of the rich man who came to Jesus asking “What must I do to inherit eternal life?”[1] Today, in contrast, we have the story of Blind Bartimaeus.

The rich man came asking what he could do to earn salvation. Jesus gave him what turned out to be an impossible task, give up his wealth for the benefit of the poor, then come and follow Jesus. Bartimaeus, on the other hand, sits at the side of the road and simply calls out to Jesus asking for mercy. Though the crowd tries to silence him, Jesus hears him and asks what he wants. “To see again” is his reply and this request is immediately granted. “Go,” says Jesus, “your faith has made you whole.” The rich man is told to give everything up and then follow, but he goes away. Bartimaeus, in a sense, is given everything when his vision is restored and told to go away, but he follows.

The stories could not be more different and yet I believe they convey much the same message, a message lost to us because we are not Mark’s original audience and we have to really do some work to understand today’s story. In particular, we have to wonder about why Mark gives the blind man a name. Names were very important in the ancient world; they weren’t just labels; they conveyed meaning, and an odd name would capture the readers’ or listeners’ attention and add to the meaning of a story. There is a Hebrew folk saying, recorded in the Bible, to indicate that a person’s name can tell us a lot about the person: Kishmo ken hu – “As his name is, so is he.”[2] It’s not for nothing that Mark names the blind beggar. So what does the name Bartimaeus signify?

Mark’s first readers were probably educated Christians living in the city of Rome, so the first thing they might have noticed about this name is that it is not Palestinian. Nor is it Greek, nor is it Latin. In fact, it’s not really anything! Scholars are pretty certain that Mark made it up. It’s an amalgam of Palestine Aramaic and Greek. It begins with the Aramaic prefix Bar, which signifies “the son of,” attached to what might be the Greek name Timaeus. In compound names, the word bar “may also denote a smaller version of something, or someone sharing a characteristic with someone, or someone who’s acquired a certain skill or characteristic.”[3]

So calling the blind beggar “the son of Timaeus” may be much more a meaningful description than merely a name. Some scholars have suggested that the name Timaeus, although clearly not an Aramaic name, may nonetheless have Aramaic antecedents and, interestingly, they suggest two rather different and even contradictory meanings.[4] The first is that it derives from the word ?im? which means “honor” or “worth” or “highly valued.” If this is the case, the beggar is the son of fame and fortune, now fallen from that high estate. Perhaps his blindness represents an attachment to that earlier condition, to his former wealth and prestige. In this case, he is like the rich man who could not give up his wealth to follow Jesus, both blinded and in darkness because of an attachment to material prosperity. They differ in that Bartimaeus is willing to give up that attachment, even throwing off his last possession, his cloak, to find hope and new life in Christ.

The second potential Aramaic origin of the name Timaeus is word ?m? which signifies impurity, uncleanness, or an abomination, almost the direct opposite of the former suggestion. This meaning would suggest that what has blinded the beggar is not wealth but poverty, not fame but shame. In the Book of Acts, there is an incident in which a slave-girl is possessed by “a spirit of divination.” She follows Paul and Silas around the city of Caesarea Philippi constantly crying out, “These men are slaves of the Most High God.” Paul gets annoyed and commands the spirit to leave her, whereupon her owners sue him because they had profted from her fortune-telling. It was definitive of who she was and when Paul cured her, she became something else, someone else, a slave less profitable to her owners and perhaps less so for herself, as well.[5]

I wonder if Mark might be saying something similar about this roadside beggar. He may have defined himself as a beggar, as a son of poverty, a son of impurity, a son of shame. He has, until this encounter with Jesus, been unable to see himself as anything else; this is who he is and this is how he provides for himself. It may be poverty and shame, but it’s his poverty and shame, and he exploits it: it’s how he is able to buy food and stay alive, but it has blinded him to any other possibility until now. If the beggar is the “son of poverty and shame,” then his situation is almost the flip-side of the rich man’s. Both are blinded by wealth – the rich man by having it, the beggar by lacking it – and, again, what sets them apart is Bartimaeus’s willingness to give up that darkness and follow Jesus, who said of himself, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness but will have the light of life.”[6]

Well, those are interesting speculations and contemplating them helps us to further understand and apply the lesson of the question asked by the rich man, but I’m not convinced that Mark would have made up a name on the basis of words from the language of an obscure, backwater of the Roman Empire. He was, after all, writing to literate citizens of the city of Rome; it is unlikely that they would have known even a little Aramaic. It is, however, certain that they would have known Greek and very likely that at least some of them would have been familiar with the literary legacy of the Greeks.

And, as it turns out, the name Timaeus is indeed a Greek name and, although rare, very well known. Some of Mark’s original readers and Mark himself would probably have been familiar with the names of Timaeus of Locri and Timaeus the historian, either one of whom might be the reason he chose to give the name “son of Timaeus” to the roadside beggar.

Timaeus the historian was an Athenean who was born about 345 BCE and died almost a century later around 250 BCE. Although some later historians would rely on his histories, others condemned him, saying that he willfully distorted the truth; in other words, he was liar. The historian Polybius derided him as an “old ragwoman,” by which he meant he was nothing more than a collector of old wives’ tales. If this historian is the Timaeus of whom the roadside beggar is a “son” or follower, Mark may be telling his readers, telling us, of the blindness that can come from untruth.

Recently, a colleague in ministry – someone from another Christian denomination – commented, “In religion and politics, one person’s truth is another person’s lie.” I could not let that stand unchallenged! I believe that is the rankest sort of nonsense. I responded,

No. Truth is truth. Lies are lies. One person’s opinion may be another person’s heresy. But truth is not subjective; it is not subject to someone’s opinion. And lies are never true. “One person’s truth is another person’s lie” is postmodernist nonsense.

When we treat lies, distortions of fact, and out-and-out falsehoods as acceptable, as someone else’s “alternative truth,” we blind ourselves to the capital-T Truth.

Yesterday, Evelyn and I attended the funeral of Fr. James Cooney who served this parish and several others in a ministry that spanned more than 60 years. He chose to have as the Gospel read at his requiem that portion of the Gospel of John in which Jesus says to the apostle Thomas, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”[7] Mark may be reminding his readers of this capital-T Truth!

If Mark is calling Timaeus the historian, the old ragwoman, the purveyor of distortions and lies to his readers’ minds, he is reminding us of Jesus’ promise, “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free.”[8] Bartimaeus, the “son” of Timaeus the liar, follower of one who distorts the truth, turns from and casts aside falsehood in favor of the capital-T Truth and, thus, receives his sight and new life. The story of Bartimaeus reminds us that “with [God] is the well of life,” as Psalm 36 says, “and in [God’s] light we see light.”[9]

It is Timaeus of Locri, though, who is the most likely candidate for Mark’s reference, certainly the most famous. He is a character in Plato’s Dialogues; in fact, one of the last of the Dialogues takes his name as its title. In that tale of a conversation between Timaeus and the philosopher Socrates, Timaeus lays out the Platonic understanding of the creation of the world and of humankind and of our place in the universe. That Bartimaeus, the “son of Timaeus,” should be blind in Mark’s Gospel is particularly poignant because in the Dialogue, Timaeus sings the praises of our sense of sight:

The sight in my opinion is the source of the greatest benefit to us, for had we never seen the stars, and the sun, and the heaven, none of the words which we have spoken about the universe would ever have been uttered. But now the sight of day and night, and the months and the revolutions of the years, have created number, and have given us a conception of time, and the power of enquiring about the nature of the universe; and from this source we have derived philosophy, than which no greater good ever was or will be given by the gods to mortal man. This is the greatest boon of sight: and of the lesser benefits why should I speak? even the ordinary man if he were deprived of them would bewail his loss, but in vain. Thus much let me say however: God invented and gave us sight to the end that we might behold the courses of intelligence in the heaven, and apply them to the courses of our own intelligence which are akin to them, the unperturbed to the perturbed; and that we, learning them and partaking of the natural truth of reason, might imitate the absolutely unerring courses of God and regulate our own vagaries.[10]

If this erudite philosopher is the referent for Mark’s tale of the blind beggar, what is it that the Evangelist is telling us? What is he warning us can cause our moral blindness?

I would suggest that it is, perhaps, self-reliance and individualism, that it is the notion that through our own faculties unaided by faith we can discern the “intelligence in the heaven,” apply it to ourselves, and “regulate our own vagaries.” Our belief in our own self-sufficiency can and often does blind us to the guidance of God and of God’s people, to the fact that salvation is promised not to individuals but to the community, that is not individuals but the entire people whom God will (in the words of Jeremiah) “bring . . . from the land of the north, and gather . . . from the farthest parts of the earth,”[11] that it is not for each of us but for all of us that Christ the High Priest “lives to make intercession . . . exalted above the heavens.”[12]

We live in a world which is sinking into darkness, in which we are becoming increasingly blind to the evils around us. We are blinded by wealth, whether we possess it or not; if we have it, we are blinded by its presence; if we don’t, we are blinded by its want. We are blinded by lies and distortions of the truth which have taken center stage in our communal, corporate, and political life. The lie of racial difference and the blindness of racial animus erupted into the news again this week as a gunman sought to enter a black church in Kentucky and, when thwarted, turned instead to a supermarket and killed two people of color in its parking lot, and yesterday when another gunman shouting “All Jews must die” killed eleven people and wounded several others in a synagogue in Pittsburgh. The blindness of political difference and the lie that violence is a solution to our disagreements seem to have led a Florida man to attempt the killing of at least fourteen political leaders with pipe bombs sent through the mail, endangering not only those politicians but hundreds if not thousands of innocent mail and transportation workers. The blindness of individualism and the myth of self-sufficiency are the subtext of nearly every political advertisement with which we are bombarded during this campaign season: we should vote, we are told again and again, based solely on and only for our own, individual interests.

We live in a world which is sinking into darkness, in which we are becoming increasingly blind to the evils around us. We are all the rich man seeking salvation; we are all blind Bartimaeus sitting with our begging bowls and our cloaks by the side of the road. Jesus is coming by. What shall we do? Will we be like the rich man holding on to whatever blinds us and turning back into the darkness? Or will we be like Bartimaeus?

Whatever it is that Bartimaeus represents, whatever it is that may be blinding us – wealth or poverty or shame, lies or complacency or postmodernist nonsense, politics or racial animus or the myth of self-sufficiency, or something else entirely – whatever it is, let us turn away from it! Let us call out, “Jesus, son of David, have mercy!” and let us pray that God will restore truth and light and sight and vision to our world.

Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost, October 28, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

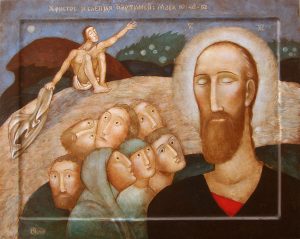

The illustration is Christ and Bartimaeus (Mark 10:46-52) by Julia Stankova (Bulgarian, 1954–), 36 x 45 cm, painting on wooden panel (2017). It may be viewed here.

The lessons used for the service (Proper 25B) are Jeremiah 31:7-9; Psalm 126; Hebrews 7:23-28; and St. Mark 10:46-52. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Mark 10:17

[2] 1 Samuel 25:25

[3] Biblical Name Vault, Abarim Publications, online

[4] See Gareth Hughes, The Name, Fame and Shame of Bartimaeus, Ad Fontes: Politics, Theology, and Christian Humanism, 26 October 2009, online

[5] See Acts, Chapter 16

[6] John 8:12

[7] John 14:6

[8] John 8:32

[9] Psalm 36:9 (BCP Version)

[10] Dialogues of Plato: Timaeus, Benjamin Jowett translation (1871), Internet Sacred Text Archive, online

[11] Jeremiah 31:8

[12] Hebrews 7:25-26

Leave a Reply