In the beginning, God said . . . and there is creation.[1] In the beginning was the Word, and the Word became flesh . . . and there is salvation.[2] When we cry “Abba! Father!” it is not us but the Spirit who speaks through us . . . and there is sanctification.[3] At the core of our faith is communication and personal relationship, and how we express that is vitally important. It is more than an intellectual enterprise. Choosing, using, hearing, reading, interpreting, and translating our words and those of scripture is a spiritual and existential exercise, as well. To demonstrate this, I have brought a prop to use this morning: this. [Bottle of Mountain Dew]

In the beginning, God said . . . and there is creation.[1] In the beginning was the Word, and the Word became flesh . . . and there is salvation.[2] When we cry “Abba! Father!” it is not us but the Spirit who speaks through us . . . and there is sanctification.[3] At the core of our faith is communication and personal relationship, and how we express that is vitally important. It is more than an intellectual enterprise. Choosing, using, hearing, reading, interpreting, and translating our words and those of scripture is a spiritual and existential exercise, as well. To demonstrate this, I have brought a prop to use this morning: this. [Bottle of Mountain Dew]

What is this? I mean, generically what is this beverage called? You might call it “pop” or “soda” or (despite the fact that it is not a cola and not a product of the Coca-Cola Company) if you were from some parts of the American South you might call it a “coke.” If you were from Great Britain or Ireland, you might call it a “fizzy drink.” If a man we have just met describes Mountain Dew as his favorite kind of Coke or calls it his favorite fizzy drink, we will automatically know something about him and we will assume much, much more, and what we know, what we think we know, and what we assume will all color our relationship with our new acquaintance.

In Greece, there are two words for these sorts of beverages. One is anapsiktiko; the other is gazoza.[4] The first means “refresher.” The second derives from the word “gaseous” and is the brand-name for a clear beverage sort of like 7-Up, but in some parts of Greece it has become a generic for all fizzy drinks.

Suppose the Gospels (written originally in Greek, as you know) recorded that Jesus drank a soft drink, and suppose that Mark told the story first and used gazoza but when Luke wrote the story he used anapsiktiko. Now suppose you are tasked with translating the Greek into English . . . what term will you use? Soft drink? Pop? Soda? Refresher? Coke? Fizzy drink? Now suppose you are a reader and you read that Jesus drank pop. Does that say something different to you than when you read that Jesus drank a soda, or a fizzy drink, or a coke? What if your translator chose to be very literal and have Mark report that Jesus drank a “gaseous drink,” and Luke say that he consumed a “refresher,” what would that communicate to you? Whatever it might be, you can bet your bottom dollar that scholars would spend decades debating the significance of Jesus’ soft drink consumption and the spiritual meaning of the evangelists’ descriptions.

OK. I know. That’s all rather silly, but it illustrates how difficult it is to translate thoughts initially expressed in one language into another, and how our understanding of the biblical text we hear in English translation can be fixed, narrowed, and limited by the word choices of interpreters. That’s important because our understanding of scripture directly impacts our relationship with God. So, I want to explore with you how that happens with one verse in today’s gospel lesson, verse 5 of the first chapter of John: “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.”[5]

Last Christmas, after I’d retired, a friend of mine who is a scholar of all things Scottish sent as his Christmas greeting this verse translated into that variant of English which Robert McNeil called “the guid Scots tongue,” the language of Robert Burns’s poetry and some of Walter Scott’s prose: “An, aye, the licht shon i the mirk, an the mirk dinnae slacken it nane.”[6] I said to myself, “If I ever again get to preach on the prologue to John’s gospel, I’m going preach about that translation.” So, today, I get my chance to explore this verse with you through the lens of the Scots translation.

It turns out, that my friend’s version is from a translation into what’s called “leid Scots,” the Scots spoken in and around Glasgow and also amongst the Scots-Irish of Northern Ireland, done by William Laughton Lorimer, Professor of Greek at the University of St. Andrews, and published in 1983 after his death. There is another, somewhat different version translated in 1901 by the Scottish-born Canadian clergyman and poet William Wye Smith. This earlier version is in what’s known as “braid Scots”: “And the licht glintit throwe the mirk! but the mirk failed to tak haud o’t.”[7]

The word that first caught my attention and encouraged me to preach about this verse is mirk. This wonderful, archaic-sounding word found in both Scots versions is the origin of our modern English murky and I think that offers a great perspective for our understanding of the light shining in the darkness!

All too often, I think, we read this verse and its theological meaning as if “darkness” were capitalized, as if the referent were some sort of powerful, personalized, cosmic evil, like the Black Archon of C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra trilogy,[8] or the Black Thing of Madeleine L’Engle’s Time Quartet.[9] And, then, of course, we move on to the unspoken, frequently unrecognized, and plainly inaccurate conclusion that it has nothing to do with us. We act as if “Darkness” is something removed from us, something vast and enormous over which we have no control and with which we have no dealings, something eternal, separate and apart from our own lives.

One of the frankly amusing things about Mr. Lorimer’s Scots translation is that while Jesus and the Apostles and nearly everyone else speak Scots, in the story of Christ’s temptations the Devil speaks the Queen’s English. In fact, Satan is the only character in the entire New Testament who speaks English. This makes Darkness and its Prince utterly unlike us, the Scottish readers of the text. The Devil is English, his darkness has nothing to do with any of us! But, now, mirk, murkiness . . . that’s another matter.

Murkiness suggests something that is both more than and simpler than darkness, something more human, less cosmic. The word connotes cheerlessness and confusion, and those are definitely characteristics we all share from time to time. We are often confused about darkness, about evil, about our own need for light and clarity. We are often cheerless, sometimes right in the midst of the most joyous of circumstances: consider, for a moment, all those people for whom this season of Christmas is, for whatever reason, a time of sadness and depression. We are too often gloomy and grief-stricken.

Yes, darkness is cosmic and universal, and the problem of evil in the world is huge. But render our verse with these alternative meanings of darkness, of mirk, of murkiness, and John’s Prologue takes on a new and immediate meaning, an intimate and personal meaning: “The light shines in our cheerlessness and confusion, but our grief and gloom do not overcome it.”

Just as I think we tend to universalize the darkness, to act as if it is some great issue that has little or nothing to do with our everyday lives, we do the same with the light. I know that as a child, when I heard this verse about the light shining in the darkness I thought it meant the Star of Bethlehem, and I don’t think I’m alone in that. That’s the problem of conflation, of course, the issue that arises because so often we don’t hear the gospel of God’s incarnation in any one its four separate and very different iterations, but rather as an amalgam of the Synoptics – a sort of stew of Matthew, Mark, and Luke (mostly Luke) all mixed together with a soupçon of John thrown in. We have, I think, Hollywood movies and television Christmas specials to thank for that, but I’m pretty sure we can give some of the blame to church school pageants.

When I was kid, my family were not church goers, but my older brother (who had gone to a Lutheran parochial high school) insisted that we go to church on Christmas Eve. Often we would end up in some Missouri Synod congregation at the early evening service which always seemed to include the children’s nativity play and it usually happened that every kid from 3 to 13 who walked in was drafted to take a part. As result, I’ve been a sheep or a shepherd in a few Lutheran Christmas pageants. I’m six feet tall and I’ve been six feet tall since I was twelve years old, so in the last pageant I was in before high school I towered over most of the other kids and, instead of being made a sheep or a shepherd, I was handed a large aluminum foil covered star and told just to hold it over my head. I was then shoved out into the chancel while someone read this bit from John about the light coming into the world and then thatother bit from Matthew about the magi following the star. And I know I’ve seen and heard John’s Prologue misused like that since becoming a church-going adult and – Mea culpa! Mea maxima culpa! – it’s probably happened in churches where I was the rector.

So we’ve got this notion that the light of the Incarnation is some blazing, cosmic, nuclear-fired interstellar thing that shines against and will eventually conquer some powerful, cosmic evil, the capital-D Darkness. But along comes the Rev. Mr. Smith’s Scots version of the gospel and pokes a hole in that idea. “And the licht glintit throwe the mirk!” Glintit!

To glint, another archaic-sounding Scots-derived word . . . the dictionary tells us that it is to make “a tiny, quick flash of light.” It brings to mind the old proverb, “It is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.” It reminds us of the Christian summer camp songs, “The little light of mine” and “It only takes a spark.” The Scots translation reminds us that the light which came into the world did not blaze forth like Sol Invictus or Helios Apollo driving his chariot across the sky and conquering the night; it glinted from a manger in the darkness of an insignificant Palestinian village. It was tiny, just a twinkling, glinting through the murkiness of human existence.

The powerlessness of darkness in the face of that light is expressed in the original Greek by the verb katalambano. At its most basic, this word simple means to take hold of. By extension, it can mean to seize, take possession of, or overwhelm; and, by further extension, to perceive, comprehend, or understand.[10] The King James Version emphasizes the latter meaning saying the darkness “does not comprehend” the light; our New Revised Standard text emphasizes the antagonism of darkness toward light saying that the darkness “does not overcome” the light.

Prof. Lorimer’s Scots version takes a similar course, but emphasizes the weakness of darkness. Not only does the murkiness not overcome the glimmering brightness, it doesn’t even, in the last wonderful words of the Lorimer version, “slacken it nane.” It does not lessen it. It doesn’t even make a dent in it. Not one little bit! To the contrary, that tiny flash of light overcomes the murkiness and confusion, the cheerlessness and gloom in our lives. “Lighten our darkness” pleads one of our prayers, “defend us from [the] perils and dangers of this night.”[11] That’s what the Incarnation is all about. It may be about some cosmic and eternal battle between good and evil, removed from our everyday lives, but much, much more than that, it’s personal: it’s immediate and it’s intimate.

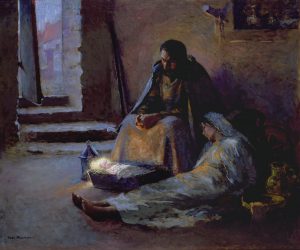

My favorite Christmas painting is by the American artist Gari Melchers, who lived, painted, and taught in Holland and Germany in the 1890s and early 1900s. Entitled simply The Nativity,[12] it shows the Holy Family not in a stable, but in a darkened room; it’s gloomy and cheerless, with bare stone walls. The battered wooden door hangs open and we can just see a bit of the foggy street beyond. Joseph sits on a stool against the wall; his hands are clasped as if in prayer; he is slumped forward, exhausted, gazing at a rough wooden box at his feet, the manger in which the baby Jesus sleeps peacefully. There is a lantern next to improvised crib, but it is not lighted; the only light in the room seems to come directly from the infant’s face. Mary is seated on the floor to Joseph’s left, her legs outstretched, her head resting against Joseph’s left thigh, her hair falling across her face; she seems to be asleep. The baby’s right hand is outside of his swaddling cloths, as if reaching for his mother; her right hand rests on the manger, as if reaching out to him in return. It’s a tender and intimate scene.

My favorite Christmas painting is by the American artist Gari Melchers, who lived, painted, and taught in Holland and Germany in the 1890s and early 1900s. Entitled simply The Nativity,[12] it shows the Holy Family not in a stable, but in a darkened room; it’s gloomy and cheerless, with bare stone walls. The battered wooden door hangs open and we can just see a bit of the foggy street beyond. Joseph sits on a stool against the wall; his hands are clasped as if in prayer; he is slumped forward, exhausted, gazing at a rough wooden box at his feet, the manger in which the baby Jesus sleeps peacefully. There is a lantern next to improvised crib, but it is not lighted; the only light in the room seems to come directly from the infant’s face. Mary is seated on the floor to Joseph’s left, her legs outstretched, her head resting against Joseph’s left thigh, her hair falling across her face; she seems to be asleep. The baby’s right hand is outside of his swaddling cloths, as if reaching for his mother; her right hand rests on the manger, as if reaching out to him in return. It’s a tender and intimate scene.

The Rev. Mr. Smith’s braid Scots version translates the Greek katalambano in the most basic way: “the mirk failed to tak haud o’t.” It’s not that the darkness fights the light, or fails to understand that light. The darkness simply fails to take hold of the light, fails to reach out and grasp it the way Mary in Melchers’ painting reaches out to take hold of her newborn infant’s hand.

That’s what the Incarnation is all about. Yes, of course, it’s about the grand and glorious cosmic struggle of nuclear-fired, interstellar light and goodness with the powers of darkness and evil, and the light’s inevitable victory. Yes, it’s about truth and justice and mercy and world peace. But in a world where children are separated from their parents and held by governments – by our own government – in cages, where children die of preventable diseases because governments –our own government – seeks to deny them health care and insurance coverage, where children go to bed and go to school hungry, and where some starve, but governments –our own government – cancels supplemental nutritional assistance programs . . . in such a world it is easy to get gloomy and depressed and believe that chaos and confusion, darkness and evil are winning.

That’s when John’s Prologue, in these Scots translations, communicates to us that at its core our faith is about relationship, and even when the murkiness seems to be overwhelming, when the Truth seems to be nothing more than a tiny flash in the darkness, if we just reach out and take hold of it, like a mother reaching for her baby’s hand, we too will receive grace upon grace, and like John the Baptizer be given power to testify to the light. Amen.

====================

This homily will be offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the 1st Sunday after Christmas, December 29, 2019, to the people of Harcourt Parish, Gambier, Ohio, where Fr. Funston will “supply” as guest clergy.

The lessons scheduled for the service (Christmas 1) are Isaiah 61:10-62:3; Psalm 147:13-21; Galatians 3:23-25,4:4-7; and St. John 1:1-18. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Genesis:1:1-2:4

[2] John 1:1-18

[3] Matthew 10:20; Galatians 4:6; Romans 8:15-16

[4] Maria Verivaki, Soft Drinks, Organically Greek website accessed 22 December 2019

[5] John 1:5 (NRSV)

[6] From The New Testament in Scots, William L. Lorimer, tr. (Canongate Books, Edinburgh:2010)

[7] From The New Testament in Braid Scots, William Wye Smith, tr. (Alexander Gardner, Paisley:1904)

[8] Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943), That Hideous Strength (1945)

[9] A Wrinkle in Time (1962), A Wind in the Door (1973), A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978), Many Waters (1986). A fifth book, An Acceptable Time, was added in 1989.

[10] Greek/Hebrew Definitions, Bible Tools (incorporating Strong’s and Thayer’s Greek Lexicons), website accessed 26 December 2019

[11] A Collect for Aid against Perils, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 70

[12] Gari Melchers, The Nativity, 1891, Gari Melchers Home & Studio, Falmouth, VA. See Gari Melchers Home & Studio, website accessed 26 December 2019

Leave a Reply