Every year, for as long as any of us can remember, on the Second Sunday of Easter the church has told the story of Thomas, Thomas the Doubter, “Doubting Thomas” who wouldn’t believe that Jesus had risen, the poster child for those who are uncertain. But, believe me, Thomas gets a bad rap! He was no worse a doubter or disbeliever than any of the others, including Peter!

Every year, for as long as any of us can remember, on the Second Sunday of Easter the church has told the story of Thomas, Thomas the Doubter, “Doubting Thomas” who wouldn’t believe that Jesus had risen, the poster child for those who are uncertain. But, believe me, Thomas gets a bad rap! He was no worse a doubter or disbeliever than any of the others, including Peter!

Consider this from the end of Mark’s Gospel:

Now after he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast out seven demons. She went out and told those who had been with him, while they were mourning and weeping. But when they heard that he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it. After this he appeared in another form to two of them, as they were walking into the country. And they went back and told the rest, but they did not believe them. Later he appeared to the eleven themselves as they were sitting at the table; and he upbraided them for their lack of faith and stubbornness, because they had not believed those who saw him after he had risen.[1]

Or this from the end of the Gospel according to Luke:

Then [the women] remembered his words, and returning from the tomb, they told all this to the eleven and to all the rest. Now it was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women with them who told this to the apostles. But these words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them. But Peter got up and ran to the tomb; stooping and looking in, he saw the linen cloths by themselves; then he went home, amazed at what had happened.[2]

So Thomas is no worse than them, no worse than us. We are all just as much “doubters” and “disbelievers,” because like Thomas we don’t really doubt. It’s not that we disbelieve; it’s that we’re afraid to fully believe. What Thomas was, and what we really are is not in doubt … we are in fear.

As Christian educator and author Verna Dozier has written in her book The Dream of God, “The opposite of faith is not doubt, but fear. Faith implies risk. * * * The faith view of reality is frightening in its openness….”[3]

We’ve been reading Ms. Dozier’s book in my Education for Ministry group the past couple of weeks, and interestingly enough it dove-tailed with some reports I heard recently on the NPR programs Up to Date and On the Media.

I really like On the Media which takes an in-depth look at the way important news stories are covered. Recently, they looked at the way the story of the so-called “caravan” of refugees from Honduras has been making its way through Mexico northward, apparently headed for the U.S. border. On the show, they look at the way a story moves from and between different media including social media like Facebook and Twitter, to cable news programs, to alternative news outlets, back and forth between them, morphing and changing and often getting blown out of proportion, as that story certainly was.[4]

On the other show, Up to Date, an analyst looked at the power of the internet and critiqued, specifically, social media like Facebook and how it can be harnessed by those who understand its power. One of the points he made was that social media gives us connectivity, but may not foster connection; it permits us to relate but not build relationships.[5] It occurred to me as I listened to these programs that, like the openness of faith Ms. Dozier noted, the openness of social media frightens us. As a result, we retreat into “tribal” corners, the so-called “internet bubbles,” in which my truth is different from your truth, in which leaders can turn the public away from facts simply by denying their validity, simply by claiming that they are “fake news.”

That is precisely what the powers-that-be did with the reports of Jesus’ resurrection. In Matthew’s Gospel, we read that news of what happened when the women visited the tomb on Easter morning was taken to the temple authorities; their solution was denial:

While [the women] were going [to tell the disciples], some of the guard went into the city and told the chief priests everything that had happened. After the priests had assembled with the elders, they devised a plan to give a large sum of money to the soldiers, telling them, “You must say, “His disciples came by night and stole him away while we were asleep.’ If this comes to the governor’s ears, we will satisfy him and keep you out of trouble.” So they took the money and did as they were directed. And this story is still told among the Jews to this day.[6]

Fake news! The powers that be paid the soldiers to spread what today we might call an “Alt” version of reality! They were afraid. The women, initially, were afraid. The soldiers were afraid. The temple authorities were afraid. The disciples were afraid. Thomas was afraid.

The openness of faith can be frightening. The openness of the internet can be a scary thing, but there are also aspects of the internet that are quite valuable. One that I have discovered is call Working Preacher; it is maintained by Luther Seminary in St. Paul, MN. It offers commentary on the weekly lectionary readings and I have found it very helpful in my sermon preparation.

Professor Karoline Lewis, who teaches preaching at the seminary, is the current editor of the website. Each week she writes a letter to its users. This week, she encouraged us to see the resurrection as relationship. She wrote:

To be clear, Thomas didn’t ask for proof. To see in order to believe is not the equivalent of requesting evidence or demanding a corroborating sign to ease our doubt. Because what is also clear? Thomas didn’t doubt. Never has been and never will be in the text, so let’s free our friend from this nomenclature and take a good look at ourselves for once. Thomas should not be a pawn for our own qualms. Thomas should not be the straw man for sermons that talk about faith’s misgivings. Thomas should not be a moral lesson so as to overcome our own uncertainties.

Thomas simply wanted, simply needed what Mary received, what the disciples received, which led all of them to utter the same confession, “I have seen the Lord.” Thomas was looking for his own encounter with the risen Jesus, not to prove that Jesus was alive once again, but to believe once again that the promise of relationship with Jesus would never be taken away, not even by those who take away life as if they hold life in their hands.[7]

Thomas feared the loss of relationship, but the truth is that most of us are afraid of relationships. Fear is why we humans shy away from relationship and often fall back on the alternative of rules; the temple authorities’ fear drove them to rely on rules that demanded Jesus’ death. Jesus, on the other hand, embraced relationship that fostered resurrection.

Jesus was not opposed to rules, but he always underscored the superior importance of relationship. Only two rules really matter, he said, and those rules encourage relationship: Love God and love your neighbor. If you do those things, all the other rules fall away because you will automatically follow them. If you can’t do that, then you need the rules.

Jesus world and society was one that needed and relied on rules, strict rules of social structure and conduct. The Middle Ages were like that. The world of the Renaissance and the Reformation was like that. Our world is like that. In fact, having given it some thought, I can’t think of a single human society that hasn’t been like that, other than (perhaps) that small community of Jesus’ first followers that we heard about in the reading from the Book of Acts this morning. But that community soon found itself in need of rules and the paradox is that we are here now contrasting relationships with rules because those rules made it possible for the community of Christ to continue in relationship through history.

The period that gave rise to our particular expression of the Christian faith, the 16th Century in England (and, indeed, throughout Europe) was particularly bound by strict structures of society and rigid rules. And it was through that societal lens that the Scriptures were translated … or (perhaps) mistranslated … into English and other European languages from their original Hebrew and Greek.

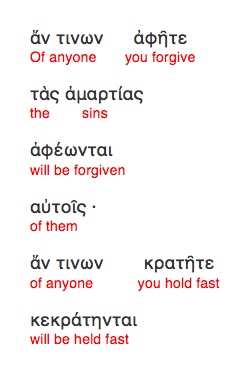

On that Working Preacher website this week, I had my eyes opened to something about a verse in today’s Gospel reading, John 20:23, that directly addresses this issue of rules versus relationship. There was there, this week, an article by the Rev. Mary Hinkle Shore, pastor of Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd in Brevard, N.C.[8] In it she sites a paper presented to the Catholic Biblical Association by a scholar named Sandra Schneiders. She points out that the traditional English translation of John 20:23 from the King James Version down through all subsequent translations including the New Revised Standard Version we heard this morning – “If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them. If you retain the sins of any, they are retained” – adds words that aren’t there in the Greek.

This is something I have never noticed before (or, perhaps, I did notice it but never considered it). I’ve had the ushers pass out to you the Greek from the original text (as currently reconstructed) together with the most basic translation of those Greek words.

In the first clause of the verse, there are two things to note. First, the Greek makes it clear that it is the person who is being forgiven, not the sins. Forgiveness is a matter of restoring relationship, not of dealing with rule-breaking. Second, you will see the term for “sins” – tas hamartias – in this clause, but in the second clause this word for sins does not appear at all. The retention of sins was added by the translators, but it isn’t at all what the original says.

Pastor Shore, and her source Ms. Schneiders, point out that Jesus empowering his church to preserve or maintain someone’s sinfulness would be out of character with the Jesus revealed in John’s Gospel. You’ll remember what that Gospel says about why Jesus came: “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.”[9] And, more importantly, the explanatory follow-up to that purpose statement: “Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.”[10] Quoting Schneiders’ paper, Hinkle writes:

Theologically, and particularly in the context of John’s Gospel, it is hardly conceivable that Jesus, sent to take away the sin of the world, commissioned his disciples to perpetuate sin by the refusal of forgiveness or that the retention of sins in some people could reflect the universal reconciliation effected by Jesus.[11]

Our traditional reading of John 20:23 just doesn’t seem to make sense. We need to rethink that, to consider it in the context of relationship not of rules.

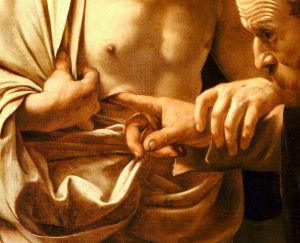

On the cover of your bulletins this morning is an odd little picture of Thomas’s hand reaching out and touching the wound in Jesus’ side. It’s a detail from what, in my opinion, is the best painting of the scene described in our Gospel reading; it is a small bit of Caravaggio’s great painting, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas.[12] I want you to pay close attention to what is happening in that picture, but first I want you to remember that what Caravaggio has painted isn’t, in fact, described in the Gospel text. John never writes that Thomas ever actually touched Jesus. Jesus invited him to do so, but in John’s story Thomas simply and immediately exclaims, “My Lord and my God!” It is only in Caravaggio’s imagination and in ours that this touching occurs.

But notice how it occurs. Thomas doesn’t simply reach out and touch Jesus … Jesus reaches out and grasps Thomas. In the painting, Jesus is holding Thomas fast by the wrist and guiding Thomas’s hand to his wound. Jesus is reaching out and embracing Thomas, holding him fast, holding him in relationship despite whatever doubts or uncertainties or sins or fears or rules or “fake news” or whatever. Jesus is acting out the very commission he has just given the disciples, holding another fast in relationship.

In a few moments, we will welcome L___ A___ G___ into the household of God through the Sacrament of Holy Baptism. When we do so, we will join her and her parents and Godparents in answering once again the questions of the Baptismal Covenant. First will be the questions about rules, about intellectual assent to propositions; those are important, but more important are the questions that come after. Those questions will ask us if we will do our part in making real the petition in our opening collect: “Grant that all who have been reborn into the fellowship of Christ’s Body may show forth in their lives what they profess by their faith.”[13] In answering those questions we will commit to continue in the Apostles’ teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread, and in the prayers. We will commit to treating all human beings with dignity and respect. We will commit to serving Christ in all persons, loving our neighbors as ourselves. We will commit to proclaiming the Gospel not only by what we say, but by how we live.[14]

Verna Dozier wrote:

The important question to ask is not “What do you believe?” but “What difference does it make that you believe?” Does the world come nearer to the dream of God because of what you believe?[15]

In answering the questions of the Baptismal Covenant, and more importantly in fulfilling those commitments, we say, “Yes, it does make difference. Yes, the world does come nearer to God’s dream because of what we believe.”

And we begin making that difference once again today as we baptize L___ A___ G___ into the household of God, as we hold her fast in relationship, because that is what we as Jesus’ community offer her: relationship not rules. Let us help her to see resurrection as relationship, let us hold her fast and call upon Jesus to hold her fast so that she may know how very good and pleasant it is when brothers and sisters live together in unity.[16]

The candidate for Holy Baptism will now be presented . . . .

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Second Sunday of Easter, April 8, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are Acts 4:32-35; Psalm 133; 1 John 1:1-2:2; and St. John 20:19-31. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

The illustration is a detail from The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Italian Baroque master Caravaggio (c. 1601–1603). It hangs in the Sanssouci Picture Gallery, Potsdam, Germany.

====================

Notes:

[1] Mark 16:9-14 (Return to text)

[2] Luke 24:8-12 (Return to text)

[3] Verna J. Dozier, The Dream of God: A Call to Return, Church Publishing: New York, 2006, pg. 11 (Return to text)

[4] On the Media, April 6, 2018, online (Return to text)

[5] Up to Date, April 3, 2018, online (Return to text)

[6] Matthew 28:11-15 (Return to text)

[7] Karoline Lewis, When Seeing is Believing, Dear Working Preacher, April 8, 2018, online (Return to text)

[8] Mary Hinkle Shore, Commentary on John 20:19-31, Working Preacher, online (Return to text)

[9] John 3:16 (Return to text)

[10] John 3:17 (Return to text)

[11] Shore, op. cit. (Return to text)

[12] The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (Caravaggio), Wikipedia, online (Return to text)

[13] Collect for the Second Sunday in Easter, The Book of Common Prayer, Church Publishing, New York:1979, pg 224 (Return to text)

[14] The Baptismal Covenant, The Book of Common Prayer, Church Publishing, New York:1979, pp 304-305 (Return to text)

[15] Dozier, op. cit., pg 79 (Return to text)

[16] Psalm 133 (Return to text)

Leave a Reply