====================

A sermon offered on Trinity Sunday, May 31, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Isaiah 6:1-8; Canticle 13 (Song of the Three Young Men, 29-34); Romans 8:12-17; and John 3:1-17. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

In the Beginning, not in time or space,

But in the quick before both space and time,

In Life, in Love, in co-inherent Grace,

In three in one and one in three, in rhyme,

In music, in the whole creation story,

In His own image, His imagination,

The Triune Poet makes us for His glory,

And makes us each the other’s inspiration.

He calls us out of darkness, chaos, chance,

To improvise a music of our own,

To sing the chord that calls us to the dance,

Three notes resounding from a single tone,

To sing the End in whom we all begin;

Our God beyond, beside us and within.

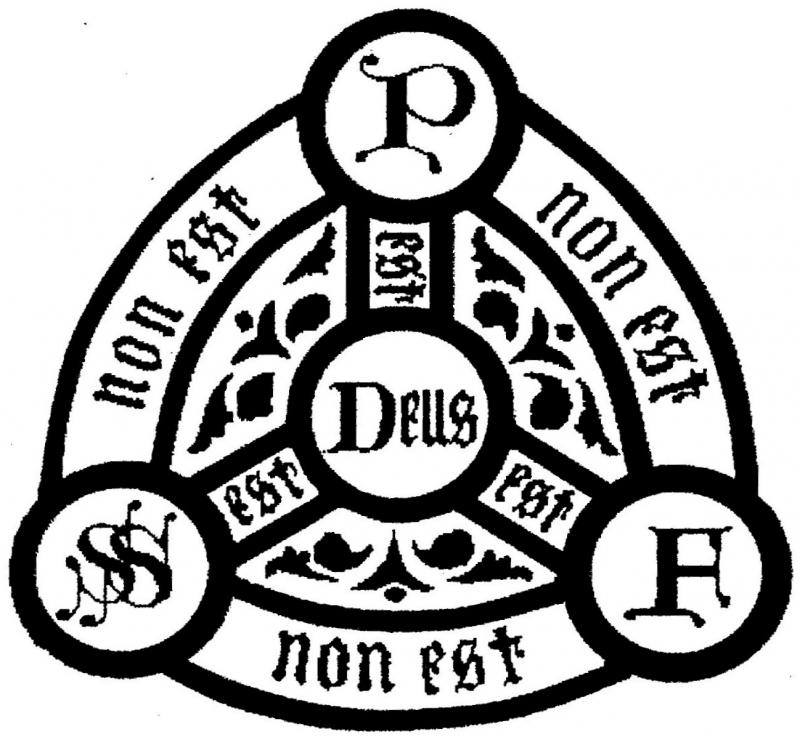

Priest and poet Malcolm Guite’s A Sonnet on the Trinity tries to express the rhythm of a dance as a way appreciating the essence of the Holy Trinity when, on this day of the Christian year, we especially celebrate. This day, the first Sunday after the Feast of Pentecost, we set aside to contemplate the mystery of God as one-in-three and three-in-one, this is the Feast of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity.

You and I have all heard many Trinity Sunday sermons filled with similes, metaphors, and analogies. We are all familiar with St. Patrick and his shamrock, with St. Augustine with his talk of Lover, Beloved and Love, with modern gender-neutral liturgies and their nearly Modalist constructions of Creator, Redeemer and Sustainer. We’ve all heard about candle flames and light and heat, about water which we know as liquid, solid and vapor, about preachers who are at one and the same time fathers, sons and husbands. Mention a trinitarian metaphor and we will all raise our hands and say, “Yep, been there, heard that one.”

And, yet . . . as familiar as we may be with all of that . . . we (as individuals) still struggle to grasp what we (as the church) mean when we (as a congregation) weekly profess our faith in God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, insisting that there are not three gods, but one God. The reason we struggle is that this doctrine, this theological perception, this self-revelation of God is a mystery in the truest sense of that word.

What we say in our creeds and in our theologies is all “code language” for this mystery. It is all an attempt to render into human words what God’s Word seems to tell us. The Trinity is not a reality that we can claim to grab hold of and test and verify and know. It is a truth that we conceive in faith, that we perceive by revelation, that we receive through the Spirit as a gift from God. It’s not spelled out in the Bible; indeed, the words “trinity” or “three-in-one” or even anything like them do not appear in Scripture. The baptismal formula “in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” is found at the end of Matthew’s Gospel (Mt 28:19), but nearly every bible scholar agrees that those words were added to Matthew’s story and that our risen and (at that point) ascending Lord never said any such thing. No, at best we find hints of the Trinity in Abraham and Sarah being visited at the oaks of Mamre by God in the guise of three angels, in Isaiah’s call to prophecy and his vision of the heavenly throne room with the seraphim repeatedly singing the three-fold sanctus of “Holy, Holy, Holy,” in Jesus’ words to Nicodemus (part of which we heard this morning) and in his words to Philip (also in John’s Gospel) “If you know me, you will know my Father also” and “whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (Jn 14:7,9).

The Trinity is a mystery, as I said, in the truest sense of that word. Our word mystery is derived from the Greek word mysterion meaning “something hidden or secret.” Even before Christianity began, the term mysterion was used to describe an experience of divine activity in human affairs. In Christian theology, we use the word mystery to describe something that is inaccessible to the human mind through mere observation or study, something which is an object of faith because it is revealed. We cannot know that God is Trinity by any human faculty, by scientific study, or by human reason; we have faith that God is Trinity because that is revealed to us in our study of the Holy Scriptures and in our personal experiences of God.

In their conversation, Jesus tells Nicodemus that one must be “born from above.” In the Greek used by John to tell the story, Jesus uses the word anothen. An alternative meaning of this word is “again,” which is how Nicodemus understands it, that one must be “born again.” What Jesus is talking about is revelation; Nicodemus misunderstands because he is thinking about mere human existence. The word anothen is used only a few other times in the New Testament and one of those is later in John’s Gospel when Christ is crucified: the soldiers cast lots for Jesus’ tunic not wanting to tear it because “the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece [ek ton anothen] from the top.” (Jn 19:23) This, I think, is a clue to Jesus’ meaning.

How many of you play (or, at least, took instruction on) a musical instrument? Remember when you were practicing, perhaps with your teacher or in a band or an orchestra, and the leader would say, “Let’s take it from the top”? So you’d play it again. And then you’d “take it from the top” and play it again . . . and again . . . and again . . . and eventually it would happen; you’d get it right. Why or how that would happen was a mystery. I remember playing the clarinet in a high school dance band and I would swear that on what seemed the seventy-eleventh time through a piece I wasn’t playing it any differently, but somehow it was different. It clicked! It sounded right! That’s what Jesus is talking about: being “born from above” is “taking if from the top” until it clicks.

Faith is a matter of practice. We practice our faith again and again; we take it “from the top;” we are “born from above;” something clicks; we get something right, not because of our human faculty or scientific study or human reason, but because of the gift of God. That’s revelation. That’s life in the Trinity, the community of God the Three-in-One and One-in-Three into which we are constantly invited.

“The Trinity is a community of divine love and mutual self-giving. Each member not only loves the other, but acts for the well-being of the other in an effective manner.” (Peter C. Phan, The Cambridge Companion to the Trinity, Cambridge University Press, 2011, page 384) If we would enter into this divine communion, we will find ourselves expected to engage in social and ethical practices reflecting God’s love and mutuality, both in the church and in the wider world. The mystery which we profess in our Creeds only means anything when it takes concrete expression in a Christian moral life of love and mutuality. The trinitarian connection between Christian worship and Christian life is particularly expressed by our being in the world as living representatives of God, acting in ways that befit the divine character. One cannot profess love of neighbor in church, then go into the world and cheat one’s neighbor in business; one cannot hear Jesus command us in church to feed the hungry or clothe the naked, then go into the world and shred the social safety net; one cannot pray “Thy will be done” in church, then go into the world and oppress those who come to our country from foreign lands for it is clearly the will of God that “the alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you.” (Lev 19:34) Few, if any of us, are capable of attaining the ethical fullness of our trinitarian confession of faith, yet the more closely we enter into the trinitarian life of communion with God through Christ in the Spirit, the more our lives can be (and will be) expected to reflect the divine attributes of love and mutuality.

That is, in all honesty, a disconcerting revelation! Life in and with the community of the Trinity remains an ethical reality that lies beyond full human realization. It is disconcerting and disorienting; it destabilizes our existence. We are most comfortable when our lives are centered upon ourselves, but the trinitarian faith revealed in Christ demands that we focus our lives in love on the well-being of others, and not simply of a single other, but of multiple others. Perhaps this is why God’s self-revelation is found in threeness.

Karoline Lewis, a professor at Luther Seminary, has pointed out that human beings are most comfortable with pairs, “easy dyads for conversation” she calls them, and with even numbers: even numbers, she says, secure a sense of order and predictability, of expectation and dependability. But, add another person “and it’s the odd man out.”

With three, she writes, we enter “a disquieting disequilibrium. A lack of control. When you have three, the dynamics change. You are forced to share a conversation, to be attentive to another besides the one right in front of you. You have to listen to more than one person. Perhaps at the same time. You have to adjudicate feelings and responses and reactions that have doubled. That’s the problem and promise of three.” Perhaps, she suggests, “God likes disequilibrium. Maybe God thinks that’s what relationships are all about. Maybe God embraces and invites imbalance. Maybe this is essential to God’s character.” (Working Preacher: The Necessity of Three)

I think that this is what Malcolm Guite means when, in his sonnet, he writes that

[God] calls us out of darkness, chaos, chance,

To improvise a music of our own,

To sing the chord that calls us to the dance,

Three notes resounding from a single tone.

The trinitarian faith is not about how shamrocks or candles or ice cubes reflect the nature of God; the trinitarian faith is about how we reflect the nature of God! This faith which calls us to love and mutuality demands that we respond to the darkness of hunger, to the chaos of homelessness, to the disequilibrium of loneliness, to the imbalance of alienation; this faith which calls us to love and mutuality demands that we “take it from the top” again and again practicing and practicing over and over, improvising until (by the grace of God) we click, until (by the grace of God) we get it right, until (by the grace of God) we truly reflect the divine attributes and live as befits representatives of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Leave a Reply