This is the second of three Sundays during which our lessons from the Gospel according to Matthew tell the story of an encounter between Jesus and the temple authorities. Jesus has come into Jerusalem, entered the Temple and had a somewhat violent confrontation with “the money changers and … those who sold doves,”[1] gone back to Bethany, and then returned to the Temple the next day. In last week’s lesson, “the chief priests and the elders of the people” demanded that he explain himself, asking, “By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority?”[2] In good rabbinic fashion, Jesus answers their question with a question and, when they cannot answer his question, he declines to answer theirs.

This is the second of three Sundays during which our lessons from the Gospel according to Matthew tell the story of an encounter between Jesus and the temple authorities. Jesus has come into Jerusalem, entered the Temple and had a somewhat violent confrontation with “the money changers and … those who sold doves,”[1] gone back to Bethany, and then returned to the Temple the next day. In last week’s lesson, “the chief priests and the elders of the people” demanded that he explain himself, asking, “By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority?”[2] In good rabbinic fashion, Jesus answers their question with a question and, when they cannot answer his question, he declines to answer theirs.

But, Jesus being Jesus, he doesn’t leave it at that: he goes on to tell three parables. First, a story about two sons, one of whom refuses to do as his father instructs but later changes his mind and obeys, the other of whom agrees to do as he is told but then fails to do so. The second, today’s story about a vineyard. And the third, a story about a wedding feast where the invited guests decline attendance so passers-by are dragged in off the streets, but one man (who fails to wear an appropriate wedding garment) is tossed back out into a place of perdition. We heard the first last week; we’ll hear the third next week. Today, we have heard “the Parable of the Wicked Tenants.”

It’s interesting that the first of these parables, the story of the two sons, is unique to Matthew, and that the third is found only in Matthew and Luke, though at different points in the Gospel timelines. In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus tells the story of the wedding feast much earlier, when he is enjoying a Sabbath meal in the house of a “leader of the Pharisees.”[3] (Luke also leaves out the bit about the guest thrown “into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”[4]) Matthew obviously has a reason for linking these three stories together in this dialog with the Temple authorities, but our lectionary divides them up and spreads them over three weeks of readings. Were I here with you for all of these three weeks, you might have gotten a sermon series from me. Alas, we are together only today, so we’ll consider only the vineyard story, but I encourage you to think about how these stories relate and what their common themes might be.

It’s dangerous to consider this story on its own, however. Taken by itself, this parable has been used by many to support a theology known as “supersessionism” or “fulfillment theology.” It is the theory that the Christian church has replaced Israel as God’s chosen people. This theology goes back at least as far as St. Augustine of Hippo and has been rightly condemned as a heresy, yet it persists. Just recently, I read this commentary by a Seventh-Day Adventist theologian:

The Christian church is the new Israel that now accepts responsibility for bearing fruit.… Now the church can only possess the kingdom if it bears fruit. …[E]ven the new recipients of the kingdom cannot presume on God’s grace. …[T]he kingdom is only for fruit-bearers. …”[J]ust as God has turned from the Jews to the Gentiles, so he will always turn from those who do not produce ‘fruit’ to those who do.”[5]

Well … with all due respect to that author, I must insist most emphatically that that is not what this parable is about: it is not about Christians replacing Jews in God’s affections! God does not “turn” from anyone. To quote the tagline of our diocese, coined by our former bishop, “God loves everyone. No exceptions.” This is a parable about God’s persistent love, not about God’s rejection.

So let’s start with the last thing Jesus says in today’s lesson. He quotes Psalm 118 asking his interlocutors if they have read it:

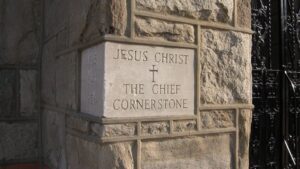

The stone that the builders rejected

has become the chief cornerstone.

This is the Lord’s doing;

it is marvelous in our eyes.[6]

Then he offers a commentary on this passage, “The one who falls on this stone will be broken to pieces; and it will crush anyone on whom it falls.”[7]

You might wonder why Jesus starts talking about a stone at the end of a parable about a vineyard, its tenants and its owner, and its owner’s servants and son. Jesus is making a rather complicated theological pun which makes no sense in Greek or English, but we assume Jesus was actually speaking Hebrew or Aramaic, in which the word for son is “ben” and the word for stone is “ében”. The stone is the son and the son is the stone.

Rejected by the decision-makers, the builders of the gate of righteousness in the psalm and the tenants of the vineyard in the parable, this son-stone becomes the cornerstone or keystone or linchpin of something much greater than a gate or a vineyard. I believe that Jesus commentary about the breaking and crushing caused by the stone is not a message of destruction, but of growth; I believe it is a reference to an apocalyptic vision in the Book of Daniel.

In Daniel 2, Daniel is called upon to interpret a dream of King Nebuchadnezzar in which the monarch sees a great statue, which is huge, extraordinarily brilliant, and frightening. Its head was made of “fine gold, its chest and arms of silver, its midsection and thighs of bronze, its legs of iron, its feet partly of iron and partly of clay.”[8] As the king watches, a stone strikes the statue, falling on its clay feet and breaking them into pieces. Then the statue collapses and as it falls the iron, bronze, silver, and gold sections fall onto the stone and shatter. Finally, “stone that struck the statue [becomes] a great mountain and fill[s] the whole earth.”[9] The statue and its materials, explains Daniel, represent earthly kingdoms, while the stone is a kingdom established by the God of heaven, a kingdom which will never be destroyed but, instead, shall stand forever.[10]

The vineyard owner’s dead son, the “ben,” becomes the “ében”, the foundation stone of that eternal kingdom. The stone is an emblem, not of destruction, but of growth and persistence.

The vineyard itself, and the vines it contains, are venerable symbols in the Jewish scriptures. The Psalmist used the vine as a metaphor for Israel. In Psalm 80 we read:

You brought a vine out of Egypt;

you … planted it.

You cleared the ground for it;

it took deep root and filled the land.

The mountains were covered with its shade,

the mighty cedars with its branches….[11]

As Jesus begins his parable, his hearers would have recalled not only this image but also the love song written by the Prophet Isaiah:

My beloved had a vineyard

on a very fertile hill.

He dug it and cleared it of stones,

and planted it with choice vines;

he built a watchtower in the midst of it,

and hewed out a wine vat in it;….[12]

These are exactly the acts Jesus describes the owner undertaking, but then Jesus departs from Isaiah’s song. In the parable, the vines of the vineyard do not produce “wild grapes” as does the vineyard in Isaiah, but good fruit from which the vineyard owner anticipates receiving his due rents. It is not the vine, not Israel, which is at fault, but the tenants entrusted with the vine, Israel’s religious and civil leaders, who have failed. If the vineyard owner is replacing anything or anyone, it is not the vine; it is not the people of Israel, it is the nation’s priests and elders.

But it is clear from the story that God really doesn’t want to do even that. The vineyard owner expects to receive the fruit of his vineyard from the vine keepers to whom he entrusted it, and he tries again and again to give them opportunity to pay it over. How many servants does he send? Let’s count them up “[H]e sent his slaves to the tenants to collect his produce. But the tenants seized his slaves and beat one [There’s one!], killed another [There’s two!], and stoned another [There’s three!]. Again he sent other slaves [There’s at least four and probably more!], more than the first, and they treated them in the same way.”[13]

Five! At least five times (and probably more), this vineyard owner tries to collect his rent; despite the disrespect and violence of the tenants he keeps sending his servants to give them another chance. And, finally, he sends his son, his obedient, willing-to-die son. That is one tolerant and persistent landlord!

A relentlessly patient vineyard owner, a faithful son willing to give up his life, a stone representing an eternal kingdom. This is a story about the love of God, not a story about anyone being replaced! That interpretation misrepresents God as inconsistent and fickle, arbitrarily breaking his promises and backtracking on what he has established. It portrays a God who makes everlasting covenants with Abraham and Moses[14] only to break them. It portrays a God who is not, contrary to the clear testimony of Christian scripture, “the same yesterday and today and forever.”[15] It makes God a liar.

Replacement theology encourages anti-semitism and, in response, because of the atrocious sentiments and statements against the Jews, it has encouraged them to loath Christianity and reject the Gospel. Supersessionism has made this parable a story of hatred instead of a tale of God’s persistent love.

Don’t get me wrong. This is a story of judgment and conflict; Matthew is writing in and for a time of judgment and conflict. Some scholars suggest that Matthew’s primary purpose is to address the concerns of his initial audience, a congregation of Jews following the way of Jesus in Jerusalem sometime around the time of the Roman destruction of Herod’s temple in 72 AD. His story of Jesus telling these parables addresses what is happening in Matthew’s and his audience’s current world. For them, the “present age” was the world of about 80 AD, the first decade after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. They were Jews who had been cut off from mainstream Judaism because of their belief in Jesus as messiah.

In the Gospel lessons last week, this week, and next, we are catching Matthew’s gospel at the downside of a pretty nasty family feud that pitted the Israelite tradition of faithfulness to the God of Abraham and Sarah against those who had found the fulfillment of the divine promises in Jesus of Nazareth. This is in no way about Christians replacing Jews; it is a struggle within the Jewish community with generations of faithfulness to God which now includes a new group struggling to understand itself as it moves in a new direction.

But we are not that community; we are not Matthew’s original audience. We are not a minority within (and rejected by) a long-standing religious tradition in which we have little or no cultural power. We are not a fledgling church trying to make sense of our situation. So we do not hear or understand this parable as they did, nor need we do so; we need not even understand it as Matthew may have intended it. We are not bound by Matthew’s context of judgment and conflict.

Instead, we are 21st Century Christians who have learned over the course of two millennia (and are still learning) that God is a God of love, persistent, stubborn, inexhaustible love for everyone. No exceptions. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost, October 8, 2023, to the people of Harcourt Parish, the Episcopal Church in Gambier, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest preacher.

The lessons were from the Revised Common Lectionary, Year A, Proper 22: Isaiah 5:1-7; Psalm 80:7-14; Philippians 3:4b-14; and St. Matthew 21:33-46. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

The illustration is the cornerstone of a Christian church. This photograph is found on various websites; I do not know the identity or location of the church. If anyone does know where this stone is located, please leave a comment and let me know.

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Matthew 21:12 (NRSV)

[2] Matthew 21:23 (NRSV)

[3] Luke 14:1, 15-24

[4] Matthew 22:13 (NRSV)

[5] John Brunt, A Parable of Jesus as a Clue to Biblical Interpretation, The Spectrum, April 10, 2017, quoting Charles E. Carlston, The Parables of the Triple Tradition (Fortress Press, Philadelphia:1975), accessed 7 October 2023

[6] Psalm 118:22-23 (NRSV)

[7] Matthew 22:44 (NRSV)

[8] Daniel 2:31-33 (NRSV)

[9] Daniel 2:35 (NRSV)

[10] Daniel 2:44 (NRSV)

[11] Psalm 80:8-10 (NRSV)

[12] Isaiah 5:1-2 (NRSV)

[13] Matthew 21:34-36 (NRSV)

[14] Genesis 17:7-14; Exodus 19-24

[15] Hebrews 13:8 (NRSV)

Leave a Reply