The last sentence of our reading from Genesis says, “And [Abram] believed the Lord; and the Lord reckoned it to him as righteousness,”[1] so this text is often treated as a story of faith. But, in all honesty, this is a story of doubt. It is the story of Abram questioning God’s promise of a posterity; it is a story of tribalism and concern for bloodline, ethnicity, and inheritance.

We humans have a predisposition to tribalism, to congregating in social groupings of similar people. Think about the neighborhood and community where you live; I’m willing to bet that your neighborhoods are made up of people for the most part pretty similar to yourselves. Aside from clearly racist practices like red lining and sundown laws, we modern Americans may not consciously organize ourselves into tribal groupings, but if we look at ourselves honestly we will find that we do. Like attracts like. As individuals, we are initially situated within nuclear families, then as we grow we broaden our social interactions to extended families, then clan, tribe, ethnic group, political party, nation.

It’s genetic: our nearest relatives, the great apes and chimpanzees, demonstrate this same family and clan predilection. And it’s religious: we find it in sacred literatures across cultures. Today’s lesson from Genesis is a case in point.

God has chosen Abram, an elderly, childless man of the city of Ur to be “God’s guy,” so to speak. God has promised Abram that he will be the father of nations; in fact, God will change Abram’s name to “Abraham” which means “father of a multitude.” At this point, however, is not clear to Abram how this will happen, and at the time of our reading, it hasn’t happened yet. Abram is getting anxious. He challenges God with this very tribal sort of concern: “Who will inherit my estate? Will it be this slave, Eliezer of Damascus?”[2]

The Hebrew here is ambiguous. Our translation describes Eliezer as “a slave born in my house,” but many scholars suggest that “a servant in my household” is probably the better reading, and this is how some other translations render the text.[3] This explains Abram’s upset: Eliezer, rather than being a native of Abram’s domestic unit, is from another city, Damascus. He is from another clan, another tribe, perhaps even a different ethnic group. Nonetheless, according to the custom of the time, he would inherit his master’s fortune were Abram to die childless. Abram’s estate would pass out of the family; his concern is tribalism, pure and simple.

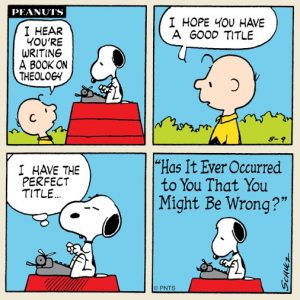

One of my favorite cartoons is a four-panel Peanuts offering from 1976, in which Snoopy, sitting on top of his doghouse , is writing a book of theology. Charlie Brown says, “I hope you have a good title.” Snoopy, thinking “I have the perfect title,” types “Has It Ever Occurred to You That You Might Be Wrong?”[4]

This is God’s response to Abram. God takes Abram outside, shows him the stars, and asks him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t actually say that, but that’s what it boils down to.[5] God’s response to Abram is, “Think again! Look beyond your tribalism.”

Many social scientists use the word “tribalism” to describe the fracturing of society that we are experiencing today. More than a decade ago, writer Wade Shepherd asserted, “The new tribal lines of America are not based on skin color, creed, geographic origin, or ethnicity, but on opinion, political position, and world view.”[6] Similarly, economist Robert Reich, who was secretary of labor in the Obama administration, wrote in an essay entitled Tribalism Is Tearing America Apart:

America’s new tribalism can be seen most distinctly in its politics. Nowadays the members of one tribe . . . hold sharply different views and values than the members of the other . . . .

Each tribe has contrasting ideas about rights and freedoms . . . Each has its own totems . . . and taboos . . . . Each, its own demons . . . ; its own version of truth . . . ; and its own media that confirm its beliefs.

And this is true of the world as a whole, this dividing of people into enclaves or “bubbles” of political or philosophical purity, to say nothing of racial and ethnic divisions.[7]

Human society is fractured by a kind of tribalist insistence on group identity that is our modern equivalent of Abram’s challenge to God. God’s response to Abram’s tribalism was essentially, “Think again!” And God’s response to our tribalism, to our insistence on our own ideas, our own totems, our own demons, our own versions of the truth, our own “identity politics” is the same; it’s Snoopy’s question, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?”

Which brings me to the reading from the Letter to the Hebrews and, especially, its first sentence which defines what faith is: “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.”[8] The first part of the definition says faith is “the assurance of things hoped for.” The word translated as “assurance” is the Greek word hypostasis, a compound word –hypo meaning “under” and stasis meaning “to stand” – thus an “under standing.” But not in the sense of intellectual comprehension, rather in the literal, physical sense of something that “stands under,” that is foundational or bedrock. In the words of Episcopal priest and New Testament scholar Amy Peeler, hypostasis “is something basic, something solid, something firm [which] provides a place to stand from which one can hope.”[9]

A few years ago, I attended a continuing education seminar at which participants were given a large sheet of paper and asked to draw a map or picture of our personal spiritual growth with a focus on that which provides stability in our lives. Of course, nearly all of us attempted to depict God as the stable center, or unchanging goal or beginning, the whatever of our spiritual journeys, but one participant didn’t do that. In fact, he didn’t draw anything at all on his paper until he was standing in front of the group (as we were all required to do). He drew some squiggles and boxes and whatever on the sheet as he described his spiritual autobiography, but then said, “What is stable in all of this is the paper!” Brilliant! The paper represented the hypostasis, the bedrock standing under his life, the foundation of faith on which the details played out and changed and developed over time, and that is really true for all of us.

The second part of the definition is that faith is “the conviction of things not seen.” We hear that word “conviction” as synonymous with “belief” or “firm opinion,” but the original Greek is elegchos which carries the sense of “proof” or “evidence.” Faith is the evidence which establishes the existence of that which cannot be seen, the proof that there is an invisible foundation for one’s life, one’s beliefs and opinions, one’s actions. “What is stable in all of this is the paper!”

Our modern tribalism insists that everyone in the tribe have the same life, the same beliefs, the same opinions, and undertake the same actions, but more than that it insists that anyone who differs to any significant degree in any of those things is outside the tribe. If we were to draw the tribes as circles on that sheet of paper, ideological tribalism would insist that each tribe is a circle that does not touch any other, and yet we all know that that is simply not true.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping, and also not static but ever-changing. That was true of Abram’s descendants, the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap, then shift and overlap in new ways. People’s lives and opinions overlap and change, but ideological tribalism, identity politics, and racial stereotypes blind us to our similarities and encourage us to see only our differences and those, falsely, as permanent.

Which brings me to today’s gospel lesson in which Jesus admonishes us to be like servants who keep their lamps lit for their master on his wedding night.[10] I suspect that most people who hear this admonition are reminded of the parable of the five wise and five foolish bridesmaids, but I suggest that we think instead of Jesus’ command in Matthew’s Gospel, “Let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven.”[11]

The purpose of the lit lamps is not simply to have lit lamps! It is to have light by which something can be done, something can be seen. The purpose of the servants’ lamps is to light the way for the bride and bridegroom, to illuminate the pathway and allow them to see the door. The purpose of keeping our lamps lit is so that people may see our “good works and give glory to [our] Father in heaven.” It is our works, our lives and actions, which matter; it is in our stories that we will find the similarities, the places where our Venn-diagram circles overlap. We may not find them in our ideologies, religious beliefs, or political opinions, but we will find them in our experiences.

There’s a Christian rapper named David Sherer who performs under the stage name Agape. In one of his pieces he puts it this way: “Hear the biography, not the ideology.”[12]

The bishops of the Anglican Communion for the past several days have been meeting together with the Archbishop of Canterbury at something called “the Lambeth Conference” which is concluding today. You may have heard about, and you may have heard that there was a bit of a division among the bishops over the place of gay, lesbian, and bi-sexual persons in the church. Some, like the bishops from America, Canada, New Zealand, and elsewhere, believe LGBTQ+ persons are and should be full members of the church entitled to access and receive all of the Sacraments, including holy matrimony and ordination. Others, particularly some from Africa and Asia, styling themselves as “biblically orthodox,” hold a diametrically opposite point of view. Some of the latter, essentially declaring that their Venn diagrams cannot possibly overlap, refused to receive Communion at Eucharists in which married or partnered gay bishops also took part.[13] Both groups put out conflicting statements. It pained me to see the Anglican Communion infected with the same sort of information-bubble, ideological tribalism that infects our domestic politics.

I read the reports coming out of Lambeth and just wished that someone, God or Snoopy or anyone, might have stepped in and just whispered in the bishops’ ears, “Think again!” I read the news about legislation coming out of Washington, out Columbus, or out of other states’ capitals, and I wish that God would say to our solons, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?”

My prayer is that God might speak those words in everyone’s life from time to time. It might shine some light on our ever-shifting Venn diagrams, reminding us that “what is stable in all this is the paper,” so that we listen to each others’ biographies, not just our ideologies. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on August 7, 2022, the 9th Sunday after Pentecost, to the people of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Canton, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was supply preacher. This is an updated version of a sermon preached at St. Paul’s Parish, Medina, Ohio, on August 7, 2016.

The lessons read at the service were Genesis 15:1-6; Psalm 33:12-22; Hebrews 11:1-3, 8-16; and St. Luke 12:32-40. These lessons are from the Episcopal Church’s version of the Revised Common Lectionary (see The Lectionary Page).

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] Genesis 15:6 (NRSV)

[2] Genesis 15:2-3

[3] See, e.g., the English Standard Version, the Geneva Bible of 1599, the Lexham English Bible, the New American Bible, the New International Bible

[4] Charles M. Schulz, And the Beagles and the Bunnies Shall Lie Down Together: The Theology in Peanuts (Holt, Rhinehart & Winston, NYC:1984), back cover

[5] He brought him outside and said, “Look toward heaven and count the stars, if you are able to count them.” (Genesis 15:5, NRSV)

[6] Wade Shepherd, New American Tribalism, Vagabond Journal, May 17, 2011, accessed August 3, 2022

[7] Robert Reich, Tribalism Is Tearing America Apart, Salon, March 25, 2014, accessed August 4, 2022

[8] Hebrews 11:1 (NRSV)

[9] Amy L.B. Peeler, Commentary on Hebrews 11:1-3,8-16, Working Preacher website, August 7, 2014, accessed August 4, 2022

[10] Luke 12:35-38

[11] Matthew 5:16 (NRSV)

[12] Benjamin Mathes, How to Listen When You Disagree, Urban Confessional website, July 27, 2016, accessed August 4, 2022

[13] David Paulsen, Conservative Bishops Refuse to Take Communion, Episcopal News Service, July 29, 2022, accessed August 4, 2022

Leave a Reply