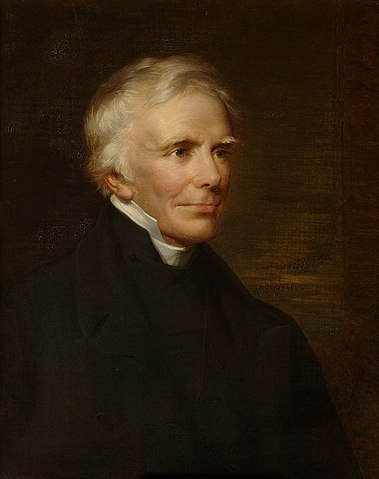

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words:

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words:

On public occasions, such as the present, the minds of Christians naturally revert to that portion of Holy Scripture, which exhibits to us the will of the Sovereign of the world in more immediate relation to the civil and national conduct of mankind. We naturally turn to the Old Testament, when public duties, public errors, and public dangers, are in question. And what in such cases is natural and obvious, is sure to be more or less right and reasonable. Unquestionably it is mistaken theology, which would debar Christian nations and statesmen from the instruction afforded by the Jewish Scriptures, under a notion, that the circumstances of that people were altogether peculiar and unique, and therefore irrelevant to every other case. True, there is hazard of misapplication, as there is whenever men teach by example. There is peculiar hazard, from the sacredness and delicacy of the subject; since dealing with things supernatural and miraculous as if they were ordinary human precedents, would be not only unwise, but profane. But these hazards are more than counterbalanced by the absolute certainty, peculiar to this history, that what is there commended was right, and what is there blamed, wrong.[1]

It was to Samuel, the prophet whom God empowered to commission and anoint first King Saul and then King David as rulers over Israel, that Keble looked in his sermon. Today, the lectionary bids us look back, in the Old Testament, to the prophet Amos and, in the New Testament, to the prophet John the Baptizer, but the application of Amos’s and John’s witness to our own time is no less apposite than was the application of Samuel’s counsel to Keble’s.

Amos was shown a vision of a plumb line, an instrument used by masons and carpenters to test the straightness and perpendicularity of walls. Amos understood the vision to mean that God was testing the moral uprightness of Israel in the way a builder tests the verticality of his building.

Amos was a farmer-poet, a man more at home with the sheep and the fig trees he tended than with the great and powerful. Nonetheless, this farmer-poet felt compelled to call out the failings of the nation’s political and religious leadership. The plumb line was not merely religious or spiritual. It tested morality, both person and public; it was political and it was economic. Speaking on behalf of God, Amos wrote:

I will not revoke the punishment;

because they sell the righteous for silver,

and the needy for a pair of sandals —

they who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth,

and push the afflicted out of the way;

father and son go in to the same girl,

so that my holy name is profaned;

they lay themselves down beside every altar

on garments taken in pledge;

and in the house of their God they drink

wine bought with fines they imposed.

Yet I destroyed the Amorite before them,

whose height was like the height of cedars,

and who was as strong as oaks;

I destroyed his fruit above,

and his roots beneath.

Also I brought you up out of the land of Egypt,

and led you forty years in the wilderness,

to possess the land of the Amorite.

And I raised up some of your children to be prophets

and some of your youths to be nazirites.

Is it not indeed so, O people of Israel?

says the Lord.

But you made the nazirites drink wine,

and commanded the prophets,

saying, “You shall not prophesy.”

So, I will press you down in your place,

just as a cart presses down

when it is full of sheaves.

Flight shall perish from the swift,

and the strong shall not retain their strength,

nor shall the mighty save their lives;

those who handle the bow shall not stand,

and those who are swift of foot shall not save themselves,

nor shall those who ride horses save their lives;

and those who are stout of heart among the mighty

shall flee away naked in that day,

says the Lord.[2]

To the king and to the high priest, as spokesperson for God he declared:

Alas for you who desire the day of the Lord!

Why do you want the day of the Lord?

It is darkness, not light;

as if someone fled from a lion,

and was met by a bear;

or went into the house and rested a hand against the wall,

and was bitten by a snake.

Is not the day of the Lord darkness, not light,

and gloom with no brightness in it?

I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.[3]

Justice and righteousness, these were the plumb and the measuring line against which the nation of Israel and its leadership were tested. This was the standard in light of which those who trampled the head of the poor into the dust of the earth and pushed the afflicted out of the way were judged. The Rev. Mr. Keble was correct to suggest we look to the prophets when we deal with questions of public duties, public errors, and public dangers. In his day, Keble saw a “growing indifference, in which men indulge themselves, to other men’s religious sentiments.” He therefore complained:

Under the guise of charity and toleration we are come almost to this pass; that no difference, in matters of faith, is to disqualify for our approbation and confidence, whether in public or domestic life. Can we conceal it from ourselves, that every year the practice is becoming more common, of trusting men unreservedly in the most delicate and important matters, without one serious inquiry, whether they do not hold principles which make it impossible for them to be loyal to their Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier?[4]

Unlike Keble’s England, our nation has no established church, “no religious Test … required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust,”[5] and yet do we not have at least a minimum expectation of morality in our political leaders? Do we not expect at least some minimum standard of decorum?

We listen to Amos’s words in condemnation of the immorality of King Jeroboam and the complicity of the high priest Amaziah and we nod in pious and solemn agreement: “God was surely right,” we think, “to make desolate the high places of Isaac and lay waste the sanctuaries of Israel.”[6] But do we apply the same moral plumb line to the leadership of our own nation? We hear the story of John the Baptizer’s death at the hand of the adulterous King Herod,[7] championing the New Testament prophet and condemning the sinful ruler, then we go to the polls and elect politicians so much like Herod as to be nearly indistinguishable.

Have we come, as Keble suggested to his congregation in 1833, to a time when we can no longer conceal from ourselves that we are trusting men and women into whose character we have truly made no serious inquiry? Have we, like the Israelites of Amos’ day, come to a time when our leadership and thus our nation does not measure up to God’s moral plumb line? I need not rehearse the stories of inappropriate conduct of all sorts by our nation’s politicians, of presidents, of senators, of representatives, of elected leaders at every level of federal, state, and local government. You have heard them as often as I have. What do you think the Amoses and John the Baptizers of today should say to them? What should they say to us?

A century ago, another poet, another prophet, Kahlil Gibran, in a sequel to his famous work The Prophet, a book entitled The Garden of The Prophet, wrote these words:

Pity the nation that is full of beliefs and empty of religion.

Pity the nation that wears a cloth it does not weave

and eats a bread it does not harvest,

and drinks a wine that flows not from its own winepress.Pity the nation that acclaims the bully as hero,

and that deems the glittering conqueror bountiful.Pity a nation that despises a passion in its dream,

yet submits in its awakening.Pity the nation that raises not its voice

save when it walks in a funeral,

boasts not except among its ruins,

and will rebel not save when its neck is laid

between the sword and the block.Pity the nation whose statesman is a fox,

whose philosopher is a juggler,

and whose art is the art of patching and mimicking.Pity the nation that welcomes its new ruler with trumpeting,

and farewells him with hooting,

only to welcome another with trumpeting again.Pity the nation whose sages are dumb with years

and whose strongmen are yet in the cradle.Pity the nation divided into fragments,

each fragment deeming itself a nation.[8]

We cannot know to what country Gibran’s protagonist Almustafa, by whom these lines are spoken, specifically referred. Gibran himself was born in Lebanon – raised and educated there and in the United States (where he lived most of his life) – and although he refused to be called a politician, he was a fierce champion of Syrian nationalism. He may have had one or all of those countries in mind when he wrote those words which were published after his death in 1933.

A 21st Century American poet, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, following Gibran’s form, published these words of prophecy in 2007:

Pity the nation whose people are sheep,

and whose shepherds mislead them.Pity the nation whose leaders are liars,

whose sages are silenced,

and whose bigots haunt the airwaves.Pity the nation that raises not its voice,

except to praise conquerors and acclaim the bully as hero

and aims to rule the world with force and by torture.Pity the nation that knows no other language but its own

and no other culture but its own.Pity the nation whose breath is money

and sleeps the sleep of the too well fed.Pity the nation — oh, pity the people who allow their rights to erode

and their freedoms to be washed away.My country, tears of thee, sweet land of liberty.[9]

Professor Keble was correct: “We naturally turn to the Old Testament, when public duties, public errors, and public dangers, are in question.” We do so, I think, because we can distance ourselves from the witnesses of the old scriptures, from Samuel, from Amos, even from John the Baptizer. But we cannot distance ourselves from our modern prophets who call on us to pity a nation we recognize too clearly as our own, a leadership we recognize too quickly as those whom we have elected.

The ancient Israelites to whom Samuel and Amos prophesied had, one might say, the comfort of saying their leaders were appointed by God. The Jews of First Century Palestine could lay the blame for their rulers at the feet of the Roman Empire which put and kept them in power. Even the citizens of aristocratic and monarchist England to whom Keble preached could escape responsibility on the ground of hereditary leadership. We have no such luxury. Our leaders are who they are because we elected them. We have to own that.

If we want leaders less like Jeroboam, more likely to measure up to Amos’s moral plumb line …

If we want leaders less like Herod the Tetrarch, more likely to gain the approval of John the Baptizer …

If (quoting today’s gradual psalm) we want mercy and truth to meet together, righteousness and peace to kiss each other, truth to spring up from the earth, and righteousness to look down from heaven … [10]

If we want justice to roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream … [11]

Then we must finally answer the Rev. Mr. Keble in the negative, abandon our own national apostasy, and affirm that we will no longer trust our politicians unreservedly in the most delicate and important matters without serious inquiry into their morals and principles.

Let us pray:

Almighty God, to whom we must account for all our powers and privileges: Guide us and all the people of this nation in the election of officials and representatives; that, by faithful administration and wise laws, the rights of all may be protected and our nation be enabled to fulfill your purposes; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.[12]

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Eighth Sunday after Pentecost, July 15, 2018, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

The lessons used for the service are Amos 7:7-15; Psalm 85:8-13; Ephesians 1:3-14; and St. Mark 6:14-29. These lessons can be found at The Lectionary Page.

====================

Notes:

[1] John Keble, National Apostasy, July 14, 1833, page 7, accessible online (Return to text)

[2] Amos 2:6b -16 (Return to text)

[3] Amos 5:18-24 (Return to text)

[4] Keble, op. cit., page 15 (Return to text)

[5] United States Constitution, Article VI, Para. 3 (Return to text)

[6] Amos 7:9 (Return to text)

[7] Mark 6:14-29 (Return to text)

[8] Khalil Gibran, The Garden of the Prophet (1933), accessible online (Return to text)

[9] City Lights Publishers, New Poems by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, accessible online. A video of the poet reading this poem can be seen at the blog of Lampros Lamprinakis, PhD, accessible online (Return to text)

[10] Psalm 85:10-11 (Return to text)

[11] Amos 5:24 (Return to text)

[12] The Book of Common Prayer 1979, Prayers & Thanksgivings, Prayer No. 24, “For an Election” (modified), page 822 (Return to text)

Leave a Reply