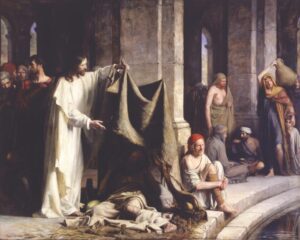

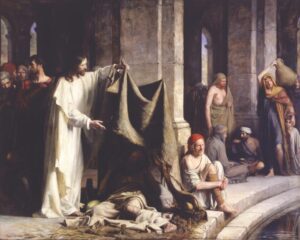

“Do you want to be made well? … Stand up, take your mat and walk.”[1]

“Do you want to be made well? … Stand up, take your mat and walk.”[1]

My father won a Bronze Star for bravery under fire in World War II. His citation for “meritorious achievement [at a battle] in the vicinity of Ensheim, Germany, somewhat casually mentions that he “was wounded by enemy artillery fire.”

The wound which the citation glides over so nonchalantly was actually multiple shrapnel wounds that pretty much tore up his right leg and required two years of surgeries, physical therapy, and learning to walk again. He was left with a significant limp and constant pain for the rest of his life, pain which he self-medicated. His drug of choice was alcohol. Some of my earliest memories include fetching for him a Miller Hi-Life beer from the fridge or the bottle of Wild Turkey bourbon in the living room drinks cabinet.

Late on the night of March 30, 1958, while driving under the influence of that alcohol, he lost control of his car on a desert highway east of Kingman, Arizona, rolled his Thunderbird convertible three times, and broke his neck. My father, though he did not die in service and was, indeed, a civilian at the time of his death, was a casualty of World War II just as surely as if he had died on that battlefield in Germany. I am certain that if, at any time during those thirteen years between his wounding at Ensheim and his death in the Arizona desert, someone had said to him “Do you want to be made well?” his answer would have been, “Yes! Hell, yes!”

Continue reading

I’m sure you’re all familiar with Howard Thurman’s meditation entitled The Work of Christmas:

I’m sure you’re all familiar with Howard Thurman’s meditation entitled The Work of Christmas: In any event, I know that Mother Lisa has been over all of that with them, so this sermon is not for them. It’s for you, their family and friends; it’s about their marriage, but it’s for you.

In any event, I know that Mother Lisa has been over all of that with them, so this sermon is not for them. It’s for you, their family and friends; it’s about their marriage, but it’s for you. Do you all know what a tort is? Tort … T-O-R-T … no E on the end; I’m not talking about those wonderful little German or Austrian pastries. A tort is a civil wrong that causes harm to another person, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the wrong. You leave a puddle of milk on the floor of your grocery store knowing it’s there, then someone slips in it and injures themselves: you have committed a tort. You speed through a stop sign, collide with another car, and injure the driver: you’ve not only broken the law, you’ve committed a tort.

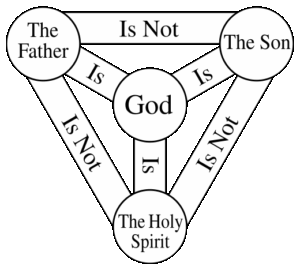

Do you all know what a tort is? Tort … T-O-R-T … no E on the end; I’m not talking about those wonderful little German or Austrian pastries. A tort is a civil wrong that causes harm to another person, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the wrong. You leave a puddle of milk on the floor of your grocery store knowing it’s there, then someone slips in it and injures themselves: you have committed a tort. You speed through a stop sign, collide with another car, and injure the driver: you’ve not only broken the law, you’ve committed a tort. A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.

A few weeks ago, as I was looking forward to my annual cover-Rachel’s-vacation gig here at Harcourt Parish, my plan was to preach a sort of two-part sermon on play and playfulness. Seemed like a good summer-time thing to do. Last week, on Pentecost Sunday, I suggested to you that playfulness is a gift of the Holy Spirit, that play is why we were made. Today being Trinity Sunday, I planned to follow-up with a few words about how a metaphor of play and playfulness can help us understand and participate in the relational community which the triune God is.  Y’all know who John Wesley is, or was, I’m sure. The Anglican priest who founded Methodism? My paternal grandparents were Methodists and they really tried to make me into one but, for some reason, it didn’t stick. To this day when Evelyn and I visit a Methodist church, I will often turn to her as we are leaving and say, “There’s a reason I’m not a Methodist.”

Y’all know who John Wesley is, or was, I’m sure. The Anglican priest who founded Methodism? My paternal grandparents were Methodists and they really tried to make me into one but, for some reason, it didn’t stick. To this day when Evelyn and I visit a Methodist church, I will often turn to her as we are leaving and say, “There’s a reason I’m not a Methodist.”  “Do you want to be made well? … Stand up, take your mat and walk.”

“Do you want to be made well? … Stand up, take your mat and walk.” Let’s have a show of hands: everyone who believes that there is a Constitution of the United States raise your hand. OK, good. Now everyone who believes in the Constitution of the United States raise your hand. Some of you might be thinking, “Wait. Didn’t he just ask us to do that?” Well, no. There’s a difference between “belief that” and “belief in.”

Let’s have a show of hands: everyone who believes that there is a Constitution of the United States raise your hand. OK, good. Now everyone who believes in the Constitution of the United States raise your hand. Some of you might be thinking, “Wait. Didn’t he just ask us to do that?” Well, no. There’s a difference between “belief that” and “belief in.”  One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”

One of the things I try to do when I read the stories of Jesus in the Gospels, when he uses an odd or striking metaphor like “I will make you fishers of people”